The JRB presents an excerpt from Triangulum, the new novel from Masande Ntshanga.

Triangulum

Masande Ntshanga

Umuzi, 2019

Read the excerpt:

~~~

RTR: 012

Date of Recollection: 02:06:2002

Duration: 5 min

I wake up to a new stain spreading itself across our ceiling. I stare at it, passing the hours it takes my aunt to get up. The geyser might be leaking again, I think of telling her when she hauls the ironing board past my room, leaving it to stand in the kitchen while she runs water for a bath. Half an hour later, the smell of her perfume permeates down the corridor and I hear her handbag drop on the kitchen counter.

I draw my covers close. ‘I’m up,’ I tell her when she knocks.

It’s no different from most mornings. I have a bath, get dressed and eat a bowl of cereal in the kitchen. Then Doris drives me to Home Affairs to get an ID made, like we arranged to do a month ago.

It’s hot out, and I still haven’t seen the machine. Nor heard from Kiran.

I lean my head against the window as the two of us go down Ayliff, looking out at the town centre while she complains about her cousin Dumisani again.

‘Isn’t the car old?’ I ask her.

‘That’s not the point.’

I shrug and lean against the window again. There’s a crowd gathered on the town square, in front of a man dressed in a robe woven from straw. The people before him drop banknotes at his feet. Behind them, two children dressed in matching straw loincloths race towards the memorial in the centre of town, wrestling and struggling to keep their feet on the plinth.

It reminds me of how Dad used to hate seeing these monuments. From the moment we first moved here, he’d likened them to celebrating one’s own prison guards. I still remember listening to him as he spoke, watching through the car window as the queen slid past us, frozen in another century, looking over a population that was kept in the dark about how much blood she’d spilt. It didn’t feel like a prison, but the remains of an alien civilisation which had now fled, its mission untenable; but not wanting to be forgotten, it had left behind unreadable signs, as out of place as hieroglyphs inside an igloo.

‘I’d appreciate it if the cleverness was kept for school,’ Doris tells me.

I apologise. ‘I’m not feeling well.’

‘Have you been taking your medicine?’

‘I have. I think it’ll pass.’

My aunt nods. We continue down the road, passing the square. ‘I’m surprised the pub’s still open,’ she says.

I look up and see what she sees. For the past four years, our town’s been slowly losing its old skin. Each month, an old shop closes down, to be replaced by a R99 clothing store, a cell phone repair shop or a café with a Coca-Cola sign.

Dad used to hate it, too, when Mom called our town quaint. The swimming baths, she meant. The bowling clubs and the horse stables. The theatre facing out towards the square and the Penny Farthing store for cakes. That was back then. Now potholes and patches of broken asphalt mark the route as Doris drives us downtown, the pharmacies alone in maintaining an unshakeable trade, their turnstiles unscrewed to allow long lines to snake out from the dispensaries.

I turn back to the road.

My aunt parks in front of a white building with a brick façade and a fading government sign. We pass through the entrance under an arch, and then take the stairs. On the first floor, Doris and I join a queue of old women sitting in plastic chairs, facing a partitioned counter with ringing telephones, groaning fax machines.

To my surprise, we don’t have to wait: my aunt gets called up next. She rummages through her purse for my birth certificate, and I fill out a form while she sits back down. Then I stand in another queue for fingerprints, thinking about the talk we had in the car.

That’s what I used to tell Dad. That I didn’t feel well. I think about the machine again, and wonder if it always meant I needed to be medicated.

The queue shortens and I get summoned to the front. A man takes my form and tells me to give him my hands. He dips my fingers in a vat of ink and presses my prints to the paper, and it’s when he’s on my second hand that I imagine seeing it.

Inside the ink.

The roiling motion of the machine.

I stare at it, but it doesn’t last.

Then the man directs me to another counter, where a woman with a cropped blonde wig tells me where to get the photographs I need to complete the process. When I turn around, I find Doris standing behind me with her purse. I take forty rand from her and head downstairs, where I hand the notes to a photographer under the arch. He stands me in front of a blank wall and takes four black-and-white photos. Upstairs again, I hand the pictures to the woman, who stamps the form.

Then Doris and I head back to the car. There’s a countdown on the radio, the Metro Top 40, too loud for conversation.

My aunt has to visit a friend in town. I lock the door behind her and sit in front of the TV, thinking about Kiran and the vat of ink.

In bed later, after she’s come home and I’m about to fall asleep, the machine returns.

This time, I don’t bother switching on Kiran’s recorder.

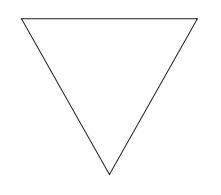

I stare at the ceiling, watching as the machine covers the new stain. The triangle appears not long after that. I turn my head to see it, but then I realise it’s upside down, reminding me of the sky that day when I was nine years old in Bhisho Park, and the swing creaked behind me as I fell.

~~~

About the book

In the Eastern Cape, a schoolgirl maths prodigy is haunted by the loss of her mother, who disappeared during the demise of the country’s homeland system.

When a strange apparition—’the machine’—visits the girl at night, she’s convinced it’s a sign from her mother, and connected to a series of abductions of local girls. With her two closest friends, she sets out to find the truth, exposing links to the area’s murky past.

Are her visions disturbed hallucinations to be medicated away? Or are they evidence of supernatural—perhaps even extraterrestrial—contact? Years later, as a gifted data scientist in a dystopic surveillance-state, she is drawn into a world of espionage, shadowy corporations, eco-terrorists and hackers through the love she feels for an elusive artist.

Presented as a message from the future, Masande Ntshanga’s Triangulum boldly mixes science-fiction with philosophy and details of South African history seldom examined. An affecting exploration of bereavement, sexuality and coming of age, this multilayered novel showcases a completely original talent coming into his full powers.