Two problems are gnawing at my heart as we leave Dar es Salaam to Morogoro on the Sunday afternoon of 22 July. First, I lost my cellphone charger the previous night at the Triple Seven Restaurant in Mikocheni. My battery is dead. Second, I’ve just discovered with an explosive shock that my visa expired yesterday. We still have six more days to spend in Tanzania. This is entirely my fault. When I entered the Tanzanian border of Namanga from Kenya on 16 July the immigration officer asked me how many days I was going to spend in Tanzania. In my excitement I told him I would be here for five days. I wasn’t sure if we were going to make it to Morogoro and Mbeya because of some budget issues we were having.

But Morogoro was one of the important reasons I agreed to join Zukiswa Wanner and James Murua on this road trip. Over the years, I had heard bittersweet stories about the ANC camps that existed there during apartheid, at Mazimbu and Dakawa. I heard these tales from former exiles I associated with in the nineteen-nineties, when I lived on the famous Vilakazi Street in Orlando West, Soweto. In fact, as a youngster in the nineteen-eighties I used to fantasise about going into exile, but that never happened. Instead, I wrote a novel called Way Back Home, which was partly inspired by my own imagined experience of exile. Zukiswa also wanted to reconnect with her past at Morogoro, as her late father was an ANC cadre who met her mother in exile.

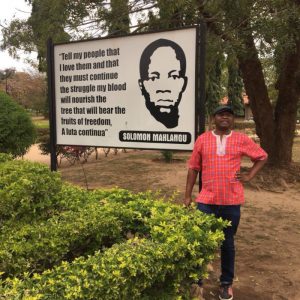

Zukiswa has already arranged a walking tour of the area with Allen Lewis Malisa, an Associate Professor and Principal of the Solomon Mahlangu College of Science and Education, which is based at Mazimbu. The institution was established by the exiled ANC members in 1978, and was formerly known as Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College, or SOMAFCO. There is no way I can miss the opportunity to explore an area that is known only to local people and exiles.

My first problem, the charger, is solved on our way to the Dar bus terminus. Our taxi driver stops on the side of the road and negotiates with a man selling phone chargers on the street. It costs me 10,000 Tanzanian shillings—about sixty rand.

The bright red Abood bus to Morogoro leaves at 5 pm, at 8,000 shillings a ticket. It is a distance of about 194 kilometres, but it takes us four hours because of the speed traps, and we arrive at 9 pm. We’re staying at Motel 88, not far from the bus terminus, and taxi fare sets us back 5,000 shillings. We don’t have the cash on us to pay for our accommodation, but the kind owners allow us to stay after we promise to pay the following day. The bill for tonight is 73,000 shillings, and it includes a delicious dinner of samaki with ugali, and a few Kilimanjaro beers.

A ball of hot, red light is already hanging in the sky when we wake up. The first thing I notice about Morogoro are the beautiful Uluguru Mountains that surround the whole area. The spectacular scenery seems to be waiting to be discovered and enjoyed. A flock of birds circles in the sky, eyeing us.

Our taxi to Solomon Mahlangu Campus arrives at 9 am. As we drive, a strange feeling of déjà vu comes over me. It’s as if I’ve been here before. Everything I wrote about in Way Back Home is exactly as I described—the village of Mazimbu Darajani, the Ngerengere River, the cemetery and SOMAFCO.

Professor Malisa welcomes us warmly into his office. Before he takes us on our tour, he tells us the history of the college, and how it was handed back to the Tanzanian government in 1992, following the exiles’ return to South Africa. According to the Prof, the area was a sisal farm before it was turned into a place of learning by the ANC. We then walk to the cemetery where some of the exiles are buried. He regales us with stories about the nearby Mazimbu settlement, where many kids, fathered by exiled South African men, have South African names such as Mandla, Tshepo, Nosipho, Sizwe, Lerato and Vusi. He also tells us about an ANC man who was killed by a hippo while obeying passion’s orders with a Tanzanian woman along the Ngerengere River.

As we leave SOMAFCO I’m thinking about how my novel would have turned out if I had been able to visit this place before writing it. I’m visualising Professor Malesa’s anecdotes about how apartheid agents poisoned the water, or the tragic death by car accident of the exiles who were finally travelling back home.

The taxi drops us back at the bus terminus where we take a daladala, a minibus taxi, to the city centre. I withdraw 350,000 shillings at the NMB Bank. With this money we are able to buy bus tickets to Mbeya Town, 512 kilometres away, near the border of Malawi and Zambia, at 30,000 shillings per person.

In the morning the motel owners give us a delicious boiled chicken for the road. The bus leaves at 10 am and we begin our twelve-hour journey. Along the road, traders converge with bowls and sacks of rice, potatoes, beans, as well as cheap goods from China. We pass some fields, the maize already high and about to ripen. As I ride in the bus, I contemplate how the people here seem to earn their livelihoods through a mixture of small-scale crops, livestock farming and trading. Their traditional way of life is reflected in their dress, the huts that dot the landscape, and their relationship with the land.

This journey between Morogoro and Mbeya boasts some of the most spectacular scenery in Tanzania. It invokes in me a deeper appreciation of what nature has to offer—the rare flowers, the mountain passes, the thousands of humongous baobab trees. I’ve never seen so many baobab trees in my life, and they conjure up an image of a mysterious, magical wilderness.

The road cuts through the Mikumi National Park, where we are treated to the sight of thousands of antelope and buffalo grazing. We pass through Iringa, Makambako and Mafinga before reaching Mbeya at 10 pm. Here we take a quick taxi ride from the bus terminus to Leda Lodge. We are all tired and want to sleep.

In the morning our taxi driver, Johnson, takes us to Barclays and African Bank, as James wants to withdraw some money. We have lunch at a restaurant called the Carnival, and at about five in the evening we take a daladala to the border town of Tunduma. It takes two hours to travel the 104 kilometres because the daladala is slow and makes lots of stops.

Two hours later we are at the Kilimanjaro train station of Tunduma Town. I feel a sudden violent pounding of my heart as I think of how I’ve overstayed my Tanzanian visa by six days. The reason we are going to the border today is to get our passports stamped on both sides, so that in the morning we don’t have the problem of the queue. As we walk towards the entrance of the immigration building, I try to formulate stories to tell the immigration officials. One of them, which seems promising, is that I was sick and could not travel. When I look at my phone for the time, I see that it has already changed from +3GMT East African time to +2GMT Southern African time. This means that Zambia, which is less than hundred meters away from where we stand, is behind by one hour. This creates a bit of confusion because the bus we’re supposed to book for Lusaka leaves at 4 am Zambian time and not 4 am Tanzanian time. It also means that our lodge across the street is in a different time zone, and we must be careful not to be late for our bus.

Like at the Namanga border, the Tunduma-Nakonde immigration officials of Tanzania and Zambia operate efficiently in one building and from the same room, separated by a counter. The immigration official tries to strike up a conversation with me while paging through my yellow fever card and passport.

‘Why do South African women like to make themselves old and white by dying their hair blonde?’ he asks me, looking at Zukiswa’s dyed head. ‘I see them on TV all the time.’

‘We have every kind of hairstyle in South Africa. It’s a free society.’

I can feel the burden of frightened guilt on my face as the official brings the stamped pages closer to his smooth, velvety black face.

‘You have overstayed your visit, Mr Mhlongo.’

‘I know, but I fell ill. I seem to have eaten something bad for my stomach,’ I say.

The official looks into the distance, then at Zukiswa, James and I. There is a smile on his lips and what looks like menace in his eyes.

‘You have to give me something.’

I’m already prepared for this talk, so I give him 10,000 shillings and my problem miraculously goes away. But James is not as lucky. His problem is not overstaying, but something more serious. Apparently his yellow fever card doesn’t have some vaccination or other, which the official is explaining to him. He has to pay 100 US dollars (about 1,400 rand) or he will not be allowed to cross over into Zambia with us. After some back and forth negotiations in Kiswahili, which last for about forty minutes, an agreement is reached. James also pays a 10,000 shilling bribe. On the Zambian side things run more smoothly, and we’re done in about five minutes.

The bus to Lusaka is 250 kwacha, and I’m shocked and annoyed to learn that the kwacha is currently stronger that the South African rand, because my budget is very low. This is part of the reason we ask our driver to take us to a cheaper place to sleep, and we end up at the Njema Hotel in Tanzania. Here we pay the equivalent of 20 US dollars per room. Zukiswa suggests that we leave our suitcases at the bus terminus so that they can be packed into the bus overnight. I’m uncomfortable with this suggestion but she assures me that people here do not steal because they are afraid of witchcraft. I agree reluctantly.

We leave the Zambia-Tanzania border early the next morning. It’s a sixteen-hour journey to Lusaka. But first I have to pay a further 35 kwacha for my luggage. As the bus travels onward I ponder the rich history and the kaleidoscopic political and cultural heritage of this area. I’ve learned in history classes that Zwangendaba, the king of the Ngoni who died in 1848, was buried somewhere here in Nakonde. This is the king who led the Ngoni people, then called Jere or Jele people, away from the Mfecane wars that King Shaka Zulu perpetrated in South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal area. This 1,600-kilometre, Mfecane-enforced migration started near modern day Swaziland and took more than twenty years. The journey I’m undertaking feels like traveling back in time and space to relive and rediscover the history of our people that has not been properly documented or told.

This is the third instalment in the travelogue of Niq Mhlongo’s 4459-kilometre journey through Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Read the first episode, Borders and Books, here, and the second, Tanzania and my Vagabond Neurosis, here.

- Niq Mhlongo is City Editor; his latest book is an anthology of short stories, Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree. Follow him on Twitter.

How to find a woman for casual sex (8679 single women in your city): http://xiysochodu.tk/2pp9?&fisiu=2FCf3WIh9U

Make $200 per hour doing this: http://cort.as/-POhi?&bacam=aV3rx8STX