Take me to the memory

of my grandmother’s hands

I want to bathe in her voice

and remember how to smile—’My Darling Thabo’, Mak Manaka

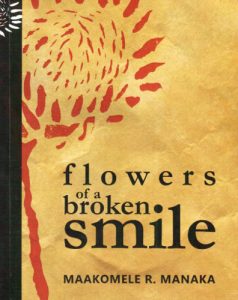

Flowers of a Broken Smile

Mak Manaka

The InkSword Publishers, 2016

Unsure of reading yet another poetry volume in the age of Insta-poets, Bongani Madondo takes a trip into Mak Manaka’s pocket-sized Flowers of a Broken Smile, and gets lost in its insatiable, complex desire for love, and romance.

1.

Poetry, to uneducated eyes and minds, might seem like a walk in the park. As with the most complex of the arts, the best of poetry makes it feel like you too could simply pour your long-locked genius onto the page and, voila, your bardic talents would at long last be appreciated by folks other than those in your head.

Like Jean-Michel Basquiat or Cy Twombly or even Jackson Pollock’s paint-smudged work, you look at it and think to yourself: mnxm, this is, like, uhm, baby poo. No great shakes.

Thus great poets suffer at the hands of social etiquette’s bottom feeders. So many poet friends have shared variations of this anecdote: You are in a taxi, or at a family gathering, where you have been freshly introduced to your new boo’s niece. Next thing, someone with a watermelon plastered across their face for a smile pushes to the front and grabs your offered hand:

‘So you write poemtree? Nice. You know I write lots of poemtree too. I have been doing it since I was, like, twelve, but, ag, you know, I do it on the DL’—they throw you a wink—‘would you terribly mind reading my poemtree?’

Or, worse: ‘Hey, please check this’—you feel mouse-trapped, with neither time nor a hole to duck into, as they slap a box full of tattered pages bound with string, and go: ‘I’d appreciate your feedback.’

My advice to besieged poets? Run! It happens to all creatives all the time. The famed trumpeter and cultural activist Hugh Masekela once confessed to me: ‘Man, it’s the bane of my life. Blame the masters. They make it all seem like the pitter-patter of “Little Boobee” toddler steps.’ How charming.

Seasoned readers can tell the difference between sublime work and good work, good poetry and terrible. Those with a trained eye can also tell the difference between a brilliant selfie and a well-composed photograph. See, even the shittiest photograph is a million times more edifying than the best of all that visual violence passing off as photography out there in Insta-la-la-land.

2.

Mak Manaka is not yet a master. He need not be; he is only 34, for chrissakes. No matter. He has been at this poetry biz for a decade or so. Refreshingly, ‘Mak the Knife’ is not an Instagrammer, or Insta-gamer, of poetry. He is a hard-working poet with something to say. A poet who has harnessed his dreams and honed the skill it takes to convert those dreams, those observations and demons in and out of his head, into discerning art. This is borne out by his latest, and much slept upon (by me), volume of verse, Flowers of a Broken Smile.

Mak Manaka is not yet a master. He need not be; he is only 34, for chrissakes. No matter. He has been at this poetry biz for a decade or so. Refreshingly, ‘Mak the Knife’ is not an Instagrammer, or Insta-gamer, of poetry. He is a hard-working poet with something to say. A poet who has harnessed his dreams and honed the skill it takes to convert those dreams, those observations and demons in and out of his head, into discerning art. This is borne out by his latest, and much slept upon (by me), volume of verse, Flowers of a Broken Smile.

Broken Smile was pressed late last year. This brave volume knows no such luxuries as multiple book launches, or, as Mak once confessed over the din of Mandla Mlangeni’s trumpet’s wails at the downtown jazz joint Niki’s Oasis, ‘a little shit review. Nothing, morena ka.’

Remember the story about how everyone feels they can paint, or write, uhm, poemtree? Ditto its critical scholarship. Not everyone can be a poetry critic, or, overall, a literary scrooge. Criticism, or what it used to be, is a highly demanding literary task, in some cases an art form on its own—see Pauline Kael’s film criticism, Stacy Hardy’s existential literary ramblings or Athi Mongezeleli Joja’s decolonial treatises on visual arts. It could be argued that, like visual art criticism, writing on poetry in the 21st century has become that most rarefied of all journalistic, as well as academic, careers. And for that reason, other than my colleague Rustum Kozain and a small cache of others in South Africa (some published in this very journal)—most being university-based scholars and laden with the arduous task of having to teach great literature to television-eviscerated and social-media-captured young minds—you can count our literary critics on one hand. You want a poetry critic? Hon, you stand more chance of howling at the moon and the moon howlin’ back at’cha than finding one.

For one, I am not and have never pretended to be either a poetry critic or literary critic. I am a yarn-spinner whose creative trade oscillates between what Americans refer to as creative non-fiction, biography, the essay form, and what I’d love to believe is social magical realism, otherwise known to myself as ‘fantasy’.

I am also one of those philistines who believes we should do away—away!—with genres. Still, for a cause dedicated to the further development, promotion and enjoyment of poetry, I’d donate a pound of my flesh.

Without poetry and poets, language as we know it will die. Without their philosophical, bizarre, and sometimes indecipherable ‘reading’ of the world, the only prophets we would be left with are the thuggish, pyramid scheme-ing enterprises passing for temples of God.

After years of doing this thing—reading and writing, listening and engaged in research, as well as writing some incredibly bad verse with the aim of attracting the opposite sex—I feel I can lay claim to having the eyes, ears, experience and trained sensibility for distinguishing between sublimity and tosh, aka what passes for art in this town and/or cow-n-tree.

Call me an enthusiastic observer. The type that, when poep-drunk, tends to call attention to themselves, mouthing off hot air about how WB Yeats’ ‘The Second Coming’ (‘It’s not called “Things Fall Apart”, kids!’) is a more lyrical and intellectually orchestrated piece of ominous beauty than TS Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’, and other arcane poetic diatribes.

But even lewd, braggart drunkards ought to return to the base. This is about Maakomele R Manaka and his ‘broken smile’.

3.

In her foreword to this volume, the pre-woke and ever-awake poet Lebo Mashile says about Manaka, who is partly of her generation, and partly one of her baton catchers:

Manaka’s offering is an extended riff on feminine aspects of love and life. The poet as a lover spirals through the hearts’ dimensions: falling, rising, breaking and longing.

For Mashile, one of the main poems, ‘Broken Flower’, broadcasts and refracts the next-level toil of a man, being a product of patriarchy, who, like many of us, is a potential nuisance in the company of women, but who finds himself ‘excavating himself through woman, who embodies the only life worth knowing’.

For Mashile, one of the main poems, ‘Broken Flower’, broadcasts and refracts the next-level toil of a man, being a product of patriarchy, who, like many of us, is a potential nuisance in the company of women, but who finds himself ‘excavating himself through woman, who embodies the only life worth knowing’.

Indeed, this volume is replete with Manaka’s mad love for women, and his devotion to the quest for love, no matter how elusive: What my Mandinka cousins in West Africa refers to as ‘diaraby’.

‘To woman,’ he writes, with that richly symbolic and alliterative swag, ‘is to live meaningfully.’

Really, though? Is it as simple as that? How about the myriad challenges—economic, spiritual, physical and otherwise, what bell hooks refers to as white-supremacist-capitalist-patriarchy—that have altered the souls of the best of women?

But Mashile reads the work as ‘of a man not exploring women as terrain for ownership’. The idea, presence and figure of a woman, literally and figuratively, pervades and perverts Broken Smile. She is the overriding muse. She is the one who got away. She ‘speaks half English, half erotica’. And she doubles up as friend, mother, granny, and as countless ‘floozies’ the poet is incapable of taming.

Manaka is a romantic lover, and is often seeking, digging. A man on a mission to ferret out the truth about his place in the world, as a man, artist, lover, son, and as a differently-abled person (Manaka was disabled at the age of twelve). His notion of romance is not restricted to reductionist conceptions like ‘love’ or ‘relationship’, or, for better and worse, ‘sex’.

Although sometimes his female characters are rendered as mere receptacles of his wanton wont—for example in the poem ‘Heat Wave’ where he aims to ‘explode/her wet and hairy gates’—he takes his desires and the characters provoking them pretty seriously. While he’s careful not to reduce romance to relationships, nor to imagine that women are just there, waiting for his randy verses to ‘wet’ their ‘hairy gates’, his art, at least in this volume, is wedded to the inter- and fore-play betwixt romance, desire and—as much as he tries the New Age man thing—women. Not unlike Salman Rushdie in the Enchantress of Florence, or Zakes Mda’s evocation of cosmological and oracular erotic powers in She Plays with the Darkness, Manaka wields his pen like an eruptive object, long dipped deep in casks of patchouli and other fabled love potions.

I have been putting off writing about Manaka and his Broken Smile for a while, mainly because I have been struggling to figure out a singular distinct feature about him. Is he just a man overwhelmed by love—love for humanity, for family, for his maternal gran’ma, about whom he writes, ‘For “B”’,

Inside the 4-room walls of matchbox dreams

The double bass of conflict

bellows the loves between siblings

But your humble smile brings tears to the eye of our storm

—or is he just another horny further-mucker, another random jack, out to jerk-off in public, creaming us off with his love incantations?

It took several rereads to arrive at the following observation, itself a work in progress: Mak the Knife is indeed a horny man, but one who dips and works his horn from the depths of his hurt and needy soul; and thus endears. And the surface of his pelvic palimpsest might conceal, on the page, his enslaving and overwhelming vice, which is to ensnare and charm the opposite sex. In short, he is led not by his yearnings, but by the demons of love, and his incapacity to hold them back. To wit, in ‘A Face to Love’:

I want to envelope the sun

beneath the sheets

and let it listen to you smile

while your skin breathes on mine

The dimples on your cheeks

tame the disability within my storm

and restore balance of my art

4.

This is a man totally grateful for, and graceful toward, the real or imagined subjects of his affection, or fiction. In her elegant collection A Human Eye: Essays on Art in Society, 1997-2008, in a chapter titled ‘The Baldwin Stamp’, the Jewish feminist poet and critic Adrienne Rich cautions the reader about humanity’s devaluation of gender, and our individual participation in it: ‘The complexity of manhood, or of womanhood—of maturity itself—may have become an archaic concept, leaving us to manic posturings of hunks and cheerleaders dressed in the flag.’ The passage is found in an expressive and expansive chapter on intertwinings and intersectionality in James Baldwin’s work; on what it means to be a man, and what it means to be American. It can also be read as an off-hand critique of capitalism and its ownership and reproduction of cheap and boastful avatars, ready to house hollow souls.

Rich’s observations echo those of Mafika Gwala, possibly the most talented and least celebrated of the Black Consciousness poets of the 1970s-1980s, who satirically chastised and ripped through the new black middle class’s posturing and performative grooming rituals in the late 1980s: ‘men and women boiled under smoldering, burnt and permed hair-dos’.

Manaka is less interested in critiquing than in declaration: he too explores the image and imagery of manhood, in constant rapport with the body and soul of a woman. And his is not the cheap posturing of packageable machismo. In ‘Lunar Love’, the man in perpetual heat is at it again:

I cannot force you

to be my heaven

or to undress me

from my misery

The desperation and tearful beauty of his voice crescendos, before coolly settling into a rather small puddle of love, with ripples forming circles away from the cause of his pain, unrequited love:

… But know this

my lunar love,

until my penexhales no more

I will not stop

reciting oceans

to your page

It would be disingenuous to reduce Manaka to a love or Romantic or plain horny poet (and none of these are synonymous). And yet every artist has, at some point, found him- or herself a dog-urine-marked terrain or thematic subject they undress their souls to, and seek to master. For Niq Mhlongo it’s often the untold nuances, the mingling dance between township wretchedness and a character’s joie de vivre. At the heart of WG Sebald’s work reside loss and decay on one hand, and the combination of bleakness and dark humour on the other. The ‘Demon Dog’ of American letters, James Ellroy, is—like the villain-hero of Manaka’s genre, Pablo Neruda—a creep and a perv, traits he channeled into prose of repulsive beauty. (He parlays his perversion and obsession into a strange devotion to unravelling the murder of his mother, the gorgeous, red haired, Jean Hilliker Ellroy.)

For Manaka—quivering in voice, though sometimes commanding, cajoling, dancing, ultimately needy—it is in, with, on, and about women—and love—that he finds his terrain.

And yet, while this is true, it may count as a narrow reading. Often, Manaka does not overtly disclose the object, or even the sex, of his desire. It could be a man now, a woman tomorrow, both of any sexual and racial orientation for all we know. He also has no time for language policing, like any good poet. He does not make a meal of his subversion, or a decolonial show of raving against the ‘imperialism of language’. In ‘Naledi’, a two-part verse written in Setswana, which he did not care to translate—binding the reader-critic in a cultural pact to act likewise—he invests in the deep tonality of the African ‘lovesick bloke’ genre, so much so that the poem raptures into music:

Gompieno

ke apesitse pelo

ka loleme

gore onkutlweNaledi,

goreng osampone?

The piece is inspired by Caiphus Semenya’s classic composition ‘Matswale’, which puts it in an unenviable position: on one hand it offers itself as an ‘extended riff’, a taut if exasperated ‘PS’ to the original song. On the other, it simply exposes the vagaries of unrequited love any man, any woman, any artist must come to terms with in their pursuit as dream weavers, and as victims of the dreams they weave.

The musical inflections are right on the money. I hear in the tear-drenched lyrics a poet who, in a total of just fourteen words, synop-sized rather immaculately the story of Marvin Gaye (Here, My Dear), a tale of love and rejection—and of newfound love, even. But it doesn’t seem like Manaka’s alter-negro, herein known as the ‘The Poet’, had ever shared a moment with Naledi. Like Ntabeni in RL Peteni’s Hill of Fools, his helplessness gets the best of him. It is, too, what endears him to the reader.

5.

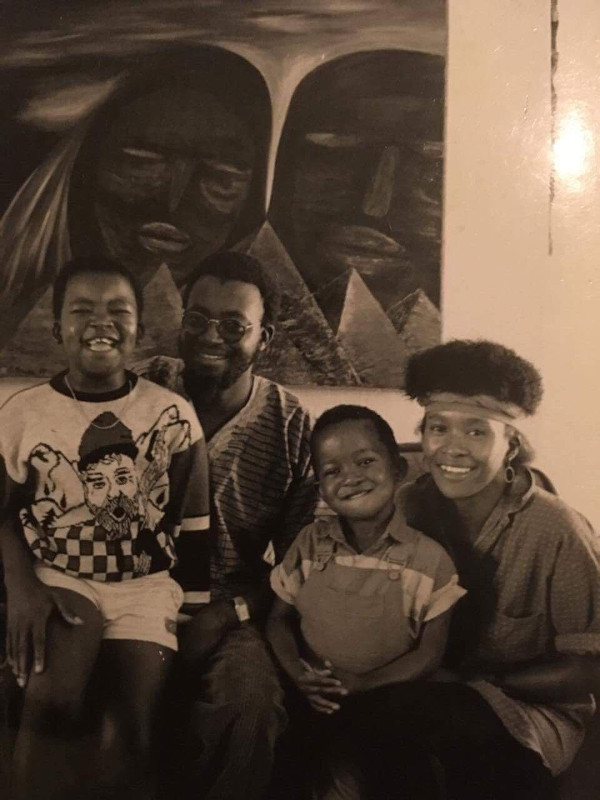

Manaka is the first of the two sons, scions of the late iconoclastic poet, playwright and painter Matsemela ‘Matsix’ Manaka, and the choreographer and performance art maven Nomsa Manaka. It was in the summer of 1995—30 October, to be precise—a few months after Mak’s twelfth birthday, when the side wall of a house he was playing in in his neighbourhood of Diepkloof, Soweto, fell on him and five of his mates, crushing them all. Little Maakomela was left permanently disabled, one of his friends dead under the rubble, and four others emotionally scarred for life. The incident would reshape his life, and art, forever: for better or worse, and every emotion beyond.

Although he has written about his pain and altered physical state in snatches of verse here and there, in ‘Bring Me Back Kele’, a letter to a previous lover—rendered meta-fictionally, as though to a Catholic priest behind a confessional veil—he lets burst the levees of his trauma:

My legs do not know me no more

I want to bury my poems of loneliness

and remember the wind on my face

the beach sand between my toesMy mind is lost inside this numb body

I search for the road back to my childhood

when days dawned with endless laughter

The novelist John Edgar Wideman once described the author of Seven League Boots and South to a Very Old Place thus: Albert Murray ‘tells the truth about the black experience just as resolutely as those runaway, star-climbing notes of a Charlie Parker solo’.

As a child of the royal township funk family numero uno, Manaka offers a non-boastful, enchanting peek into his childhood in the poem. His funky, ‘bluey’ notes are rendered uncaged, feral, and reveal another deep wish altogether. The poem harkens back, in tight verse, to how he and his younger brother grew up in a family punctured with the ‘romantic giggles of my parents’.

The biographical snatches of the pain he invokes are elevated by cinematic imagery, which in Manaka’s hands de-pixelates and dissolves into ‘star climbing notes’, on which he rides:

The sounds of my father’s red wine

jazz on canvas

The midnight music of his typewriterMy mother’s pantsula moves in the kitchen

The sunlight of hide and seek between my brother and I …

The penultimate stanza is a beautiful echo of Nina Simone’s ‘I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to be Free’:

I want to live in the memory of my name

My grandfather’s name

I want to know how it feels to be alive

I want to know how it feels to remember

and love the mirror again

Cue Nina:

I wish I knew how

It would feel to be free

I wish I could break

All the chains holding meI wish I could say

All the things that I should say

Say ’em loud say ’em clear

For the whole round world to hear

That pretty much goes to the heart of Flowers of a Broken Smile. It also sums up the life and times, thus far, of Mak the Knife. A rebel lover, seeker and philosopher of street poetics in the Byronic tradition, Manaka performs a spellbinding feat, combining and advancing his mad hermeneutics of can’t, cunt and Kant.

Only an artist who has nothing to lose, for he has already lost so much, can pursue that so unflinchingly. Therein, there to the fore, lies his beauty.

- Bongani Madondo is Contributing Editor. His collection of essays, Sigh, the Beloved Country, was recently shortlisted for the UJ Prize for English Writing, Main Prize. He writes on music, photography, poetry, and politics.

Index

Authors

- James Ellroy

- Niq Mhlongo

- JAlbert Murray

- WG Sebald

- John Edgar Wideman

Artists

- Jean-Michel Basquiat

- Jackson Pollock

- Cy Twombly

Musicians

- Hugh Masekela

- Marvin Gaye

- Caiphus Semenya

- Nina Simone

Poets

- TS Eliot

- Mafika Gwala

- Rustum Kozain

- Lebo Mashile

- Pablo Neruda

- WB Yeats

Critics

- Stacy Hardy

- Athi Mongezeleli Joja

- Pauline Kael

Books

- A Human Eye: Essays on Art in Society, 1997-2008 by Adrienne Rich

- Enchantress of Florence by Salman Rushdie

- Hill of Fools by RL Peteni

- She Plays with the Darkness by Zakes Mda

Topics

- Black Consciousness

- Gender

- Language

- Love

- Masculinity

- Romance

- Sex

Mak is my all-time favourite poet.

Bongani Madondo keeps shining ever so bright in his reviews. Such an enlightening soul. This review makes you fall in love again – fall in love with whoever and whatever it is you long for. He gets you fulfilled and equally salivating for more. He has painted Mak Manaka writing in a way that you are left with no choice but to read his poems, his writings and longing and panting for more.