Zakes Mda was the keynote speaker at the Sunday Times Literary Awards last night.

Mda won the Barry Ronge Fiction Prize, for his novel Little Suns, and Greg Marinovich won the Alan Paton Award for non-fiction, for Murder at Small Koppie: The Real Story of the Marikana Massacre.

In his keynote speech, Mda spoke about how fiction exposes the truth behind the facts, and how great historical fiction is more about the present than it is about the past. Read the full address here:

.@ZakesMda is the keynote speaker at the Sunday Times Literary Awards #STLitAwards pic.twitter.com/uJjpONxXly

— Jennifer Malec (@projectjennifer) June 24, 2017

Your excellencies, ladies and gentlemen. I was asked to speak strictly for fifteen minutes but I would beg your indulgence and allow me, because I’m a bit long winded sometimes, to add three-and-a-half minutes or so.

The Sunday Times editor, Mr Bongani Siqoko, tells me ‘illumination of truthfulness’ is the main criterion of the Alan Paton Award, which was established in 1989 for non-fiction works. He believes it applies to fiction as well, and quotes Albert Camus: ‘Fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth.’ I thank him for inviting me to give this talk. I think the topic is quite apt in this age of ‘truthiness’, ‘post-truth’ and ‘alternative facts’.

I must begin by saluting the Sunday Times for establishing these awards and for maintaining them for so many years. I am honoured that I was the first writer to win the inaugural Sunday Times Fiction Prize with my third novel, The Heart of Redness, some 16 years ago.

I must also salute the Sunday Times for its sterling work in journalism, particularly investigative reporting. You and your colleagues have added value to our young democracy by taking your watchdog role seriously. Democracy cannot function without freedom of expression in general and of the media in particular.

Some of you might know of Lorraine Adams, who first caused literary waves with her debut novel, Harbor. She wrote this work of fiction after spending years reporting on Afghanistan and Iran for the Washington Post and winning a Pulitzer Prize for investigative journalism. In her journalism, she is reputed to have dug out hidden stories on crucial issues such as xenophobia, immigration and terrorism. It was therefore a major surprise when she decided to quit the profession.

There was even greater astonishment when she revealed she was leaving journalism for fiction so that she could write the truth. She explained that it was only with fiction that she could address the truth behind the facts. Whereas the journalist views truth in terms of witnessable and observable scenes, she added, the novelist pierces into a privacy where the truth resides.

'Fiction pierces into the truth behind the facts' – @ZakesMda #STLitAwards pic.twitter.com/O6IgfywqgV

— Jennifer Malec (@projectjennifer) June 24, 2017

She is correct. Journalism answers the simple question: what happened? It is the same question that is answered by most forms of non-fiction, including history. What happened? Of course, there are attendant questions, such as how and why it happened, but the key story lies in the event. Fiction, on the other hand, goes much further, and answers the question: what was it really like to be in what happened?

Talking of the genesis of her fine book on the bitter rivalry of two women who are neighbours, The Woman Next Door, Yewande Omotoso tells a NPR interviewer, ‘I was really looking at what is it like, particularly for the Marion character, to have been someone during the apartheid days who didn’t necessarily resist apartheid, disagree with it, but kind of went along. What is it like now, you know, post-apartheid?’

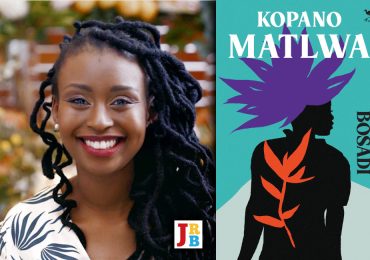

What is it like? I am sure it is the same question that Kopano Matlwa attempts to answer with her suspenseful prose as we follow the young doctor, Masechaba, trying to reclaim her life in Period Pain, or Bronwyn Law-Viljoen’s The Printmaker as we search for an answer to the enigma of the printmaker’s solitary life. What was it like to be Hennie, an Afrikaner teenager in the Orange Free State of the 1980s, who has to escape his abusive father, and embarks on a remarkable journey in search of his sister? We experience Hennie’s life, we are not just told about it, we experience his life with him in Mark Winkler’s The Safest Place You Know.

What was it like to be in what happened? It is a question whose answer gives us a sensory experience of the event. Fiction is experiential because it is transportational, and vice versa.

'Fictional is experiential because it is transportational, and vice versa' – @ZakesMda #STLitAwards pic.twitter.com/REadA63EeG

— Jennifer Malec (@projectjennifer) June 24, 2017

To address this transporting question the writers create fully realised characters, protagonists and antagonists and their allies, struggling to achieve their objectives and overcome obstacles in a compelling narrative arc. These characters may be based on real-life people the writer has known, or may be composites of same. They may even claim to have emerged from imagination. But we know that the line of demarcation between imagination and memory is very blurred. We imagine from what we know; in other words, what we remember. Memory itself is essentially fictive, and since we are what we remember, our work creates us as we create it.

'Our work creates us as we create it. We are always writing ourselves, in the same way that we are always writing the same book' – @ZakesMda pic.twitter.com/keYU05Grr8

— Jennifer Malec (@projectjennifer) June 24, 2017

Into whatever we create as artists we bring the baggage that is our own biographies, whether we are conscious of that or not. A lot of what we create in a character is drawn from us, the creators, and from our experiences. We are always writing ourselves in the same way that we are always writing the same book.

The important thing about conventional fictional characters is that they do not function in any credible manner until their actions are motivated. The few exceptions that defy this convention are such postmodern narrative modes as magical realism. In traditional fiction, there is a practical ‘why’ behind a character’s objectives and behaviours. Her actions are not only motivated but justified as well. This means she is who she is because of her life experience, of her history. Fiction is very big on causality. Her actions are therefore psychologically, not necessarily morally, justified. This tells you that every writer of fiction worth her salt is a psychologist, a keen observer of human behavior and mental processes. It is small wonder, therefore, that Sigmund Freud drew most of his groundbreaking conclusions—resulting in psychotherapy, ‘the talking cure’, as it was called—from studying characters in novels rather than from analysing live subjects. A whole new branch of psychiatry known as psychoanalysis was founded by analysing novels.

In the academy these days fiction is used in many other subjects, not only in psychology, history and philosophy, because fiction pierces into the truth behind the facts. Sipho Noko, an LLB. student, told me on Twitter the other day that he had never read an African novel before until my novel, Black Diamond, was prescribed at the University of Pretoria Law School for a topic titled ‘Law from Below’. When I wrote that novel—a layman in the field of law—I never imagined that book could be a law school textbook.

where is Tumi, What will happen to the Visagies??? wish I could read more

— sipho (@SgNoko) August 11, 2016

indeed, I am doing LLB @UPTuks & Black Dimond is prescribed as we deal with a this topic "Law from below".

— sipho (@SgNoko) August 11, 2016

Suggest something. Sipho never read a novel before until University of Pretoria Law School prescribed Black Diamond https://t.co/ahierjmhnS

— Zakes Mda (@ZakesMda) August 11, 2016

Another lawyer, Advocate Maru Moremogolo, wrote to me about Little Suns: ‘Your book brings context to judicial powers of traditional leaders, a perfect timing—#Dalindyebo—how the King wanted some of his judicial powers returned from the magistrate.’ He thought I was being prophetic, I thought I was just telling a story.

I was once astounded when I learned that Ways of Dying, another one of my novels, was prescribed at an architecture school in the United Kingdom. When I wrote that novel I never imagined I was writing about architecture. Yewande Omotoso, who is an architect in another life, once tried to explain how the novel relates to architecture, a field I know nothing about. But I forget now what she said.

The ability of fiction to operate so comfortably across all these diverse disciplines lies not only in its descriptive powers or its capacity to delineate structural problems but in its facility to examine interiorities. The interior experience is absent in journalism, as it is in most non-fiction. The search for the interior experience has resulted in the emergence of narrative journalism in recent times, and of new journalism in the last century, where the practitioners try to apply the techniques of fiction—such as point of view, and plot, and various other narrative devices—to journalism. You have seen this practice applied quite successfully in The New Yorker and to some extent in Granta. One noted non-fiction genre that has mastered the intricacies of hybridity is memoir. Memoir, unlike biography or autobiography, uses the tools of fiction to capture the essence of an aspect of the authors life. Like fiction, it explores interiorities. The publishing industry in the Western world has set distinguishing features between memoir and traditional autobiography and biography, to which it adheres faithfully. Of course, writers always experiment, and transgress genres. Autobiography is about the writer, she is the subject in a historical chronicle of her life and events that shaped it from the time she was born to a determined period. A memoir, on the other hand, is not about the writer, but about something else as experienced by the writer or those close to her. A memoir therefore must have a subject, because the writer is not the subject. For instance, the subject might be Alzheimer’s. A memoir must have a central theme, for example the author’s struggle to cope with a husband who is gradually losing his memory. A true memoirist works from memory, hence the name of the genre, because she is not a chronicler of history, she mines her memory and tries to capture the feelings and emotions she had at the time of the event. Her account is enriched by the distortions of time, by obliviousness, by faulty recall, by amnesia. The fidelity is to the emotions rather than historical accuracy. That is why you can conflate characters in a memoir and reinvent new contexts to capture and represent to the read the feeling and sometimes the philosophy. The emphasis is on emotional truth.

History, like journalism, answers the question: what happened? We write historical fiction to take history to the level of: what was it like to be in what happened? The story of Mhlontlo that I write in Little Suns was well known to me from the time I was a toddler. It is part of family lore. Even after I had researched its historical aspects, it still remained a series of anecdotes, surface stories lacking subtlety. It was only when I was writing it as a work of fiction, exploring what it was really like to be Mhlontlo by recreating his exterior and interior worlds, and the worlds of those who surrounded him, protagonists and antagonists, their loves, their losses, their gains, victories and defeats, that the emotional import hit me. Anger swelled in my chest. To my embarrassment I was caught screaming one day, ‘Damn, this is what they did to my great grandfather.’

The injustices done to amaMpondomise by the British endure to this day under the ANC regime. The amaMpondomise continue to be punished for having stood against British colonialism. Like most writers of historical novels, I write historical fiction to grapple with the present. Great historical fiction is more about the present than it is about the past. That is why the lawyer could relate the past I was reimagining about to present contestations. The past is always a strong presence in our present.

'I write historical fiction to grapple with the present. Great historical fiction is more about the present than the past' – @ZakesMda pic.twitter.com/MTkC9puHGL

— Jennifer Malec (@projectjennifer) June 24, 2017

Traditional historians believe that history is objective reality. For me history does not have an objective existence. It exists only as an absence. We don’t have direct access to the past; we cannot scientifically and objectively observe its facts. We experience history through words, through storytelling and through chronicles of events and dates. Therefore, history is textual; our attempts at separating it from literature are tenuous. History is as subjective as journalism. I know, you think you’re objective. Observe how The New Age, on one hand, and the Sunday Times, on the other, report on the same event. It is bound to read like two different events. The value-laden words, the choice of words, the incidents selected or left out, and the angles that the reporters take will surely reflect their subjectivities. If contemporary journalism cannot be objective about contemporary events, what more of history, which is shaped by its necessary textuality?

History is the story of the victor. That is what I try to correct. In doing so I make it ‘her-story’ as well. South Africa presents us with a good example of the creation and imposition of a narrative that legitimises the ruling elite of the day. The colonisers wrote history from their own perspective, always to validate their privileged position. The subaltern groups were denied a voice. They were even erased from the landscape so that when the coloniser arrived in southern Africa the lands were vast and empty and the natives non-existent.

'History is the story of the victor. That is what I try to correct. I try to make it 'her-story' as well' – @ZakesMda #STLitAwards

— Jennifer Malec (@projectjennifer) June 24, 2017

The colonialist dismissed as fanciful oral traditions that located ancient kingdoms and empires in the region dating hundreds of years before colonisation. When the coloniser’s own ethno-archeologists excavated towns and settlements dating more than a thousand years ago, the proponents of ‘vast empty lands’ created alternative narratives attributing them to alien civilisations—sometimes even from outer space. They were the victors and could therefore recreate the past in their own image.

Now a new order exists in South Africa. Like all regimes before it the new dispensation is narrating the past from its own perspective, recreating and reshaping it to palliate the very present it continues to mismanage with impunity, erasing the contribution of some from the annals of history, and lionising the current crooks, the harvesters of matundu ya uhuru, the fruits of freedom.

The truth of fiction can give context and shed new insights on the stories unearthed by your investigative reporting. It gives them longevity and digestibility. Fiction is even more essential in this age when shamelessness and impunity among the ruling elite and ‘corruption fatigue’ in the populace are leading South Africa to perdition.

Thank you.

One thought on “[The JRB Daily] Fiction is essential in a corrupt society—Read Zakes Mda’s Sunday Times Literary Awards keynote address”