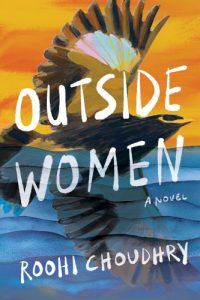

The JRB presents an exclusive excerpt from Roohi Choudhry’s debut novel Outside Women, which will be published in March 2025.

Roohi Choudhry

Outside Women

The University Press of Kentucky, 2025

~~~

Chapter Nine: Sita

Sita awoke tumbling across slick floor. There was no time to gather her wits. She was pinned against the side of the deck by a massive crate crushing her ribs. Another lurch of the ship, and the crate creaked backward an inch—enough for her to scramble out. Not a moment too soon. The floor keened again, and women fell against each other, shrieking. The crate smashed into splinters.

One woman wailed, ‘It is rakshasas come for us! Risen from the black water!’

The ship lurched, and her sentence slid into cries. Above the confusion, Tulsi’s authoritative voice rang out, a little higher-pitched than usual. ‘Calm yourselves, silly girls,’ she commanded. ‘It is a storm, nothing more.’

Sita wanted to believe her, even as she clung on to a bolt with clammy fingers. Black water beasts were only a tale. But even now, after days on the ship, she still shrank away from the sight of that endless sea. Because maybe there were no devis to save the world and no rakshasas to condemn it. Maybe no nightmare monsters pursued her in waking life. But wild nature still laughed at the foolish joys and plans of people. Nature leapt forth over the waves as everything she’d built drowned.

Eventually, the waters calmed, and the women rearranged their bedding as best they could to return to sleep. But Sita could not rest easy. Her stomach remained clenched in the morning. She was unable to touch a morsel of breakfast. Still, their daily tasks awaited them. She followed Tulsi up the ladder. They were part of the group cooking today.

They squatted on the deck under the beating sun and cleaned grain and lentils. Something of this was familiar. Like rice thrown high to land back onto rattan. Her village, her people laid to waste the water rising the baby wailing the water as high as her hip Ayamma a bony bundle with sickness the sun relentless the earth cracked.

Sita reached for the cumbu. Sturdy grains sifted through her fingers. Again and again, she ran her fingers though clean water, freshly washed hair. Once, she’d longed for such abundance. But this poor man’s millet was not rice. And her family was gone.

A nudge from Tulsi. ‘He’s watching.’ She indicated Raju nearby and tilted her chin back to her own hands picking and discarding dirt. Sita bent to her task. The mass of cumbu under the bright sun was a blur. Sita squinted to focus her eyes on individual grains. The first wriggle seemed to accord to the ship’s rhythmic motion. She scooped the lilting grain along with a few others and brought her hand closer to her face. Another squirm as if to escape and jump overboard. Then more of them were alive in her cupped hands. Wet and tender.

Sita cast the maggots from her body, but they would not let her go. They clung to her wrists and sprang onto her foot. She swatted them and ran to escape them, unseeing until she stopped against the railings, and her eyes were open wide. Far below, the ocean was not the color of the sky or the river. The mighty color stretched and filled the horizon up until the bottom curve of the sky.

Sita’s knees gave. She leaned over the railings and retched hard. Then, she relaxed and let them drag her away, shedding grains of millet.

The surgeon smiled. His teeth were yellow and crooked. He shook his head when he spoke and raised an index finger in admonition. This, then, was the same in every language. Stop causing trouble, little girl. The trumpet rested longer and lower on her chest this time.

He sent her below decks with Raju, who said she’d been instructed to sleep off ‘fever by reason of sunstroke.’

‘You’re lucky the surgeon likes you.’ He smirked. ‘But don’t expect your antics to get you out of work next time.’

She settled back in her corner of the lower deck and shivered. Her section was almost empty. Most women were still topside, except one who was heavy with child and was perhaps also instructed to rest. She heaved herself up off her blanket and waddled over.

‘Why aren’t you up there with the rest of them, girl?’ she asked. ‘Are you sick?’

Sita only nodded, unsure of her memory. It was entirely possible she’d seen maggots in the cumbu, but her terror had been sourced in something far darker. Decay at the foundation. The ground beneath her feet was no longer certain but instead had become a writhing morass that could swallow her whole.

‘Yes,’ the woman was continuing. ‘Many people have this nausea on the ships. It will pass. Only remember this when you’re expecting a child one day! You will look back on this sickness and laugh.’

Sita tried for a smile but failed. No fairy-tale return to her own village could be possible. She’d already accepted that much listening to Tulsi’s bitter recollections. No marriage day from her courtyard, as she’d grown up playing with her friends. The past had rotted away and so, too, the image of the person she thought she’d become.

But maybe in this new land—in Natal—she might have a child. Perhaps not in the way of custom. But she might still be able to bear that daughter from her dream who would rescue her from the trials of this samsara. There was hope yet.

The woman, Pushpa, stayed and talked for the rest of the afternoon. She said she would join her husband in Natal. He’d set sail six months ago and then sent for her. It was a land of great riches, she assured Sita. Fortunes abounded for those who were willing to apply themselves. The savages did not work hard; that was why the white people needed to bring others in, Pushpa explained. The five years, the plantations. Her husband told her everything in a letter dictated to a friend and read by the village Brahmin. He’d told her to hide her pregnancy from the agent. They hadn’t found out until she saw the doctor at the harbor, and by then, they’d spent too much to leave her behind. Besides, her baby was still at least three months away. Her son would take his first breath in that new land across the ocean.

‘I was afraid of crossing the water. But my husband said what we’ve heard is not true. Those beliefs about black water are just superstition. The whites travel all the time, and they still have their souls intact.’ Pushpa hesitated here. ‘Anyway, look at us,’ she continued. ‘Here we are, floating in this ship. A miracle of the white people. It protects us from the evil of the open ocean.’

This time, the surgeon laid a hand on Sita. Instead of the trumpet, he pressed a palm to her chest. When Sita inhaled and broke through her fluttering breath, he grinned wide. She watched his hand on her breastbone fall with her exhale. And then again.

Finally, he withdrew his hand. But as she turned to leave, he grabbed her forearm. His fingers dug into her flesh, and his other hand grasped her hair. He ran his fingers down the length of her plait and lingered over the woven grooves. Frantic, Sita reached for the table where the surgeon kept his gleaming instruments. But he caught her and pinned her arms together with one arm and clapped his other hand to her mouth. His wet lips dropped to her neck.

Sita raised her knee, swung back, and kicked his shin as hard as she could. Jolted, his teeth sank into her neck. He sprang back to wipe her blood from his mouth, and Sita struggled loose. She wrenched open the cabin door and ran past the women waiting outside, down the ladder below deck.

‘Don’t say anything,’ Tulsi insisted. ‘They’ll believe him. And then he will come after you for his revenge.’

‘But I have the wound. The wound will prove it.’

Pushpa shook her head. ‘He’ll say you made it up. Or else that you’re mad. He’ll remind them of that day you were fevered on the deck.’

‘But I can’t go back there!’

Tulsi squeezed Sita’s hand. ‘Don’t worry. We won’t let you go back alone.’ Pushpa made soothing sounds. Another woman nodded, and another. You won’t be alone, they said.

In wonder, Sita glanced at the circle beginning to form around her. Their faces were varied. Scars carved stories across the cheek of one; another’s complexion was almost night—a color from which she had once recoiled. Sita had raised herself above them in her mind. But by making this journey, they were no longer different. So Tulsi once told her when she’d pressed food in her palm. So this circle now reminded her. In making this sea crossing, they were strangers no longer.

After the crewmen extinguished their lamps in the evenings, the women’s murmured gossip faded into slumber. Sita listened to this drift with her eyes wide open. The hours pooled slow as syrup around her wakefulness. The first few times this happened, she cursed her fate as she tossed in a sweaty tangle. But soon, she came to welcome the nights free from that same repeated dream of pursuit.

One night, restless, she sat up and let her eyes adjust until she could make out the peaks and valleys of the landscape. She stood and placed her foot into a crevice left between a folded knee and another’s splayed arm. And then, her other foot eased into another empty slot. Tiptoe by tiptoe, she made excruciating progress.

She didn’t get far before she was startled by someone shifting onto her heel. But after that, every night, she got a little further along in this adventure. In darkness, the shapes could be a tiger ready to pounce or a cobra slinking into brush. Creatures forming behind her eyelids, she reached out her palm to find her way forth as real danger blended with fantastic.

A hand closed tight around her ankle. ‘Sita!’ An urgent whisper from below. ‘Be careful!’

It was Pushpa. By degrees, Sita lowered onto her haunches. Reaching out, she found Pushpa’s round belly, where the woman’s own palm rested.

‘What are you doing?’ she demanded in a low whisper. ‘You almost hurt him.’

‘I’m sorry, akka! I was just … I couldn’t sleep.’

‘Aren’t you tired? You cooked lunch today, and that white man made you exercise too.’

‘Yes. But I lie awake anyway.’

‘Why?’

Sighing, Sita ran a shaky palm across her face. She hadn’t slept in days. Memories of her home flickered. But when she reached for them, they extinguished quick as a candle flame. Her family felt like a made-up story in contrast with the ship’s reality. ‘I think about my village. And where we will go. And what will happen. And—so much.’ She shook her head.

Pushpa clicked her tongue. ‘Silly girl,’ she muttered. ‘You’re just a girl.’

‘You aren’t much older,’ Sita retorted. She’d grown weary of Pushpa’s maternal superiority. Just like Anjali and the other women from the village who looked down their ample bosoms at her. Unmarried, unmother. She wasn’t a real woman to them.

‘Still,’ Pushpa continued in her knowing tone. ‘Maturity comes after marriage. You’ll see one day.’

Sita laughed without mirth. ‘Marriage. Not for me, not anymore. The black water ate it up too.’

This time, Pushpa’s cluck of impatience was sharper. ‘Come now! All this black water nonsense. Hasn’t Tulsi akka journeyed before? Just stories trying to stop us from being brave.’

True, Tulsi had returned from the journey. But not unscathed. To the other women, she shrugged and made wry comments about the dangers. ‘What black water? Ayyo, it isn’t black you need to worry about. Worry about white. Watch your back for white skin’s black heart.’ Tulsi made the others giggle at her stories of greedy overseers and harbor pickpockets.

But without an audience, Tulsi’s practiced manner fled. Her face was lined by bitterness. Once, as they sweated together over a vat of lentils in the cramped galley, Tulsi muttered, ‘What use this food? Fattening us like cattle for the kill.’ Then, as if startled she’d spoken aloud, she pursed her lips and refused to explain herself further.

Sita returned her attention to Pushpa’s dim outline. How did she come by such certainty? Only by desperation. She was the guardian of new life, after all. She needed to be sure she was doing right by that duty.

Overcome by this realization, Sita reached out her hand, found Pushpa’s, and squeezed hard. Startled, the other woman paused her chastising. ‘You are right, akka,’ Sita whispered. ‘Sleep now.’

Pushpa’s pains came on while she was cooking with a group of them on the deck one afternoon. She’d insisted on joining them. Tulsi held her hand; another tested the warmth of her brow. Raju came to see about the commotion, and one woman said, ‘Help us carry her down the ladder. She’ll be more comfortable there.’

But he turned on his heel and returned with the surgeon. Heaving her up together, the men carried Pushpa away. She called out behind her in pain or fear. Sita and the others trailed after the surgeon, whispering among themselves, ‘This is not the way. How can men birth a child?’ He waved them away.

They sat up late that night, awaiting news. Exhausted, some of the women began to fall asleep. After another yawned and curled up, Tulsi got to her feet.

‘I can’t wait anymore. I’m going to see what’s happening.’

Those who were awake looked away. They were forbidden from climbing above deck except for scheduled work, exercise, or washing. And they certainly weren’t allowed unescorted inside the officers’ cabins where the surgeon sat. So far, none of the women had been severely punished. But they’d all been made to witness the men whipped unconscious on the deck—the ones who’d resisted work and another who complained about the food.

As Tulsi turned to leave alone, Sita made up her mind and jumped up. She would not let her fear of the surgeon paralyze her. She would share in this trial as the others had shared in hers. A cold gust greeted the two women as they emerged from the ladder. They ran across the open deck and hid behind a dinghy. Light spilled out of the galley on the other end, punctuated by the crewmen’s voices. This end was cast in darkness. They edged toward the officers’ cabins.

Sita shivered as the wind lashed against her bare arms. The ocean was hungry tonight, hurling and beating against the ship like a petulant child. Sita’s stomach roiled as she was thrown against one side of the railing. But she followed her friend as they tiptoed inside the narrow corridor lit by gas lamps. All was quiet, and the surgeon’s cabin was empty.

Back outside, Tulsi began to climb the ladder up to the highest level. They would be exposed to the rest of the deck if the moon should emerge from behind clouds, and Sita tried her best to crouch as small as possible against the ladder. Tulsi stopped just before the top rung. She sprang back a step and landed on Sita’s fingers.

‘He’s there,’ she whispered. ‘Around the corner. He has something in his hands.’ Her voice wavered. ‘Something small.’

‘It must be the baby. I want to see.’ Sita edged farther up the ladder. Tulsi seemed reluctant to step aside but was strangely limp too. Peering up over the top, Sita saw the surgeon a few feet away. His looming shape was outlined by the flickering lamp Raju held. Their voices were too low for Sita to make out. The surgeon held a bundle wrapped in cloth. Too small to be a person, surely. The bundle was still.

Sita’s breath caught in her throat. Where was Pushpa? Why were they standing so near the railing? She wanted to look away. But her eyes were fixed on the surgeon’s arms outstretched. Farther, his arms over the edge. An easy tumble. The bundle gulped and disappeared without a sound. No peace, no journey for the child. Only suffering and trial forever tangled in the ocean.

‘I saw them take him,’ Pushpa whispered.

Raju had carried her below deck the next day and deposited her on a blanket. Her face was drawn into shadow, her eyes far away. Sita dropped water between her lips with a spoon. Tulsi massaged her back with a little oil stolen from the galley as Pushpa whispered, over and over, ‘They think I don’t remember. He was a boy.’

Chapter Ten: Hajra

Approaching Durban, the plane crosses a sea both foreign and familiar. I once bid farewell to another corner of the Indian Ocean when I left Pakistan. But even that shore didn’t belong to me. I’m a child of the mountains, not the sea.

Through the plane window, the Drakensberg range’s misty slopes greet me. Imagining the hillsides I have known, I spy dirty blue rivers snaking between them. Haphazard towns of mud and brick side by side. Alleys twist darkly, rusty steel gates set all the way along and houses teetering above. Children balanced on rooftops fly kites into sunset skies. Grandmothers chew betel nut and shoot red spittle into steel bowls. Vespas skirt around cricket matches. Wives perch behind drivers, legs pressed prim to one side. They roar through the streets and out into the clear-breathing country, where plants in little clay pots are set in rows along whitewashed garden walls. A baker slides the long handle of his pan into a fiery tandoor set deep in the earth. Because the ground is cool at the surface but aflame within. I imagine I am coming home to you, Peshawar.

Two bumps of tire against tarmac, and we’ve landed in Durban, which is about as foreign to me as Peshawar has now become. Wheeling a creaky cart toward baggage claim, I am briskly aware of my skin and the skin around me. I am camouflaged against a gradation of my color. Pale beige with freckles and green eyes, warmer hue on others with tawny curls, dark-brown foreheads, and waist-length black hair on a pair of sisters. And the brown-black skin of the woman at Immigration: ‘Welcome to South Africa,’ she says with her stamp on my passport.

Outside is a warm afternoon. Peeling off layers of clothing, I find a taxi, and soon, we’re speeding away from the airport. Sleeplessness rakes its fingers through my senses. Everything is in pieces; everything is new. Zululand. I landed in Durban, but that is a white man’s name. Sir Durban, no less. Up and down the hills. The city is laid at my feet. Thorny bush, concrete downtown, peeling plaster near the harbor. Midwinter, and I expected yellow grasses. Instead, green adorns every corner. Palm trees persist. Colonial homes withstand the belching highway. Coral, powder blue. Coppery mosque dome and minarets wink at the sky. At a red light, a man raps at my window with a bouquet of feather dusters under one arm. And against a slope rising above is a sight as familiar to my memories of Pakistan as the mountains: a cardboard and tin shanty town.

Off the highway, we turn onto a broad beachfront avenue. Vendors line the walkway with handicrafts arranged on their allocated ground. Across from them, condos rise up high. Restaurants are shuttered, and neon shellfish are unlit.

But something here belies the quiet weekday. This place portends discovery for me. I can taste the thrill of it in each breath of salt air.

We arrive at my reserved accommodation in a block of furnished holiday apartments. An air of decrepitude lurks in the alley between dingy pastel buildings, only a street or two from the beach. A middle-aged Indian man meets me at the front, polyester tracksuit zipped over his belly. His name is Mahesh, but he says to just call him Manny. He pants as he hauls my suitcase up two flights of stairs, and his grin bares several gold teeth. I’m grateful for his hospitality until he calls me ‘baby,’ and I become more suspicious of his manner. At my flat, Manny fishes the key out of his jacket and dangles it in my face.

‘You’ll be here all alone?’ He shakes his head. ‘I just don’t know. A bit funny for an Indian girl to be all alone.’

I take the key from his hand. ‘I live alone in New York City. I’ll be fine.’

‘Still, still. Things are different in Durban. If you need help, you just call, and Manny will come to the rescue.’

I manage a nod and bolt the door behind me. Inside, drapes are drawn across the far end of the room. I drag them open to a cloud of dust, and afternoon sun floods in from a sliding glass door. In the distance, barely visible from the tiny balcony, is a small patch of sea. It’s enough to lift my weariness and the vague disquiet Manny left behind. I run a comb through my hair, lock the flat, and set out for the beach.

The sand is strewn with the strange leavings of the ocean: seaweed like molted snakeskins, shells in pearlescent shards, splintered driftwood. I sling my sandals over a hooked forefinger and roll my jeans up to my calves.

The tide is colder than I expected. Far away, this same giant lowers its muzzle and laps up against Pakistan’s southern edges. My zigzag path to this shore feels more unlikely than ever. The stray laughter of a long-dead woman was like a message in a bottle I retrieved on yet another continent. But I’ve also begun to wonder if her call was never a floating, fragile thing. Maybe my connection to her story is rooted in the earth. And my pilgrimage to Durban was written before I was born. The ocean encourages such improbable ideas.

The waves lap forward. I let my feet sink into sand and sway in time with the tide. A strip of seaweed wraps around my legs like an embrace, then lets go. Did she come here, the laughing woman? She, too, might have gripped the shifting sands with her toes. Maybe she, too, was repulsed and enraptured in equal measures by the slimy touch of seaweed. I wonder if this land was a friend to her sometimes or if it represented only hardship.

When I return to the flat, I’m overcome by fatigue. Fridge empty, I resort to stale crackers and miniature packets of nuts left over from the flight. As I eat, children shriek in the hallway and a television drones through the wall. I’m startled to find my cheeks wet with tears. I didn’t think I was sad about my lonely meal. But sobs quickly follow suit as if boiling to the surface. It’s so unexpected that I hardly know what to do with myself. When the sobs pass as sudden as they came, my shoulders and chest are looser than they’ve been in months. I fall into bed and dreamless sleep.

The next day, I explore the network of streets around my building. An alley leads to a modest strip mall featuring a convenience store, a boarded-up chemist, and a takeaway that sells fish and chips, samosas, roti, biryani, as well as a few mysterious items listed on the board: bunny chow, mutton pies, Bombay crush, patra.

At the convenience store, I strike up a conversation with Reshika, the owner. Her plump face is smooth, and her hair is black. But her patient eyes lend her the air of a mother, so I’m not surprised to learn that the teenage boys hanging around are her sons.

Like Manny, she’s shocked that I’m staying alone and offers to find me a more suitable situation renting from a ‘nice Muslim family.’ Inwardly recoiling at the thought of an aunty nosing about my papers or disapproving of my nocturnal habits, I make polite excuses. I stock up on the limited provisions available: beans, eggs, milk, toilet paper. Reshika eyes my finds doubtfully.

‘How you getting around?’

I tell her about the rental car I’ve reserved, but when she learns that I plan to take a taxi to pick it up, she won’t hear of it.

‘Young girl staying alone, and now she must take a taxi? Durban is not so cold, even in July.’

I manage to keep a straight face and accept her offer to drive me.

Later that afternoon, one of her sons at the cash register, Reshika and I climb into her ancient Toyota and set off. I jump at the opportunity to learn more about her. She tells me she grew up a few miles up the coast in Verulam, a town familiar from my research into the plantations. She’s from a large family, most of them still in KwaZulu-Natal. Reshika met her husband at the local Indian high school, she says, and I realize she must have grown up during Apartheid.

She asks about my work, and I share the basics. ‘I was doing research about Indians in South Africa and the indentured laborers who first came here. I found out about the work they did with Gandhi—protests and marches. Women as well, especially with Kasturba, his wife. I want to learn about those women. I was curious because it wasn’t common at the time for women to do anything outside the home.’

Reshika snorts. ‘Nothing much has changed, eh.’

I like her more and more. ‘True.’

‘Kasturba bai lived here in Durban, neh? I think somewhere in Phoenix. That what you came for? To visit her house?’

‘Well …’ I hesitate. ‘I saw a picture of three Indian women. They were protesting here in Durban a long time ago. I haven’t been able to stop thinking about them. They’re even in my dreams! And—’ I pause to gather the shadowy details that have eluded my grasp. ‘It’s hard to remember, but I’ve had this dream before. Or it was different. But they’re familiar, I think. Maybe that’s crazy.’

Reshika is quiet as she pulls into the car rental parking lot. She pulls up the hand brake and sits for a moment staring ahead. ‘I never read much books and all. But no one taught about dreams in school anyway. They left out everything important, neh? Dreams are important. My grandma, mummy, my aunties, all the elders say so because they know. Schools don’t know. You mustn’t say it’s crazy. We must listen when the world talks. You came here because you listened, and that’s good.’

We slip out of our seat belts and proceed into the rental office, saying nothing more about it. But I’m buoyed by her response. Her affirmation is the only one I’ve received for my journey.

~~~

- Roohi Choudhry was born in Pakistan and grew up in southern Africa. She holds an MFA in creative writing from the University of Michigan and is the recipient of a New York Foundation for the Arts fellowship and residencies at Hedgebrook and Djerassi. She worked as a researcher in criminal justice reform and public health, wrote for the United Nations, and facilitates creative writing workshops for community organisations. Her stories and essays have appeared in Ploughshares, Callaloo, Longreads and the Kenyon Review.

~~~

Publisher information

Would you risk your own life to pursue justice for a stranger? Two migrant women—separated by geographies and generations—face this same devastating choice.

Lured away from her home in eighteen-nineties India, Sita is brought to South Africa as an indentured servant—one among millions funneled by the British to replace the recently abolished slave trade. One hundred years later, Hajra, a Pakistani scholar, is forced to flee to New York City from her home in Peshawar after witnessing a violent act meant to target her. She loses herself in academic research until she comes face-to-face with a photo of a laughing, defiant young woman brandishing a banner in protest. Inexorably drawn to this woman, Hajra travels to South Africa to learn more and unknowingly traces Sita’s path.

With raw imagery and rich sensory detail, Roohi Choudhry’s incandescent debut novel Outside Women intertwines the narratives of two women painfully yet valiantly carving their existences outside of patriarchal and colonial spaces as they search for kinship and strength in solidarity.