In Show Me the Place, Hedley Twidle displays an earnest curiosity about how to inhabit a world that seems to tend ever more towards the incurious, writes Wamuwi Mbao.

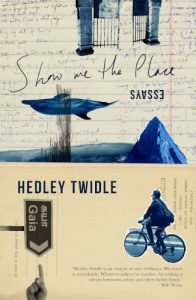

Show Me the Place

Hedley Twidle

Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2024

There’s a template for writing about essays, isn’t there? You expound for a bit about how the essay is a vehicle for displaying the pliability of human thought. Then you talk about how your chosen collection of essays—in this case, South African writer Hedley Twidle’s new book—is a masterly arrangement of writerly avidity, and you add in a handful of quotation snapshots that attempt to demonstrate the breadth and range of the collection. That’s also to convince you, the reader, that you should find the book as interesting as I, the reviewer, did.

So, we’d usually start by making a bouncy generalisation like, ‘a good essay should produce the environment for us to find an idea interesting’; or we might try something prosy like, ‘at the level of craft and technique, we expect that any essay writer worth their salt …’ and see where we end up. Essays invite pale imitation, the reviewer lead-footedly trying to keep up with the aleatory music of the essayist’s pen. The essayist drops something uncommon as though it’s everyday knowledge (of course you knew that Mary Renault was JFK’s favourite author; naturally, you knew the name of the sangoma HF Verwoerd was alleged to have kept on retainer), and the critic responds by trying to match this display of arcane knowingness with their own.

The essay format is a companionable discipline, accommodating both good writers and bad. In recent years, essay collections have long been fetish objects for a certain kind of writer, especially those keen on solemnising their names with that flavour of literary high seriousness that makes you eligible for an academic chair. Yes, you’ve got three novels in the can, possibly a collection of short stories too. But what will truly make you a serious writer is a collection of published punditries with a fervid title: Obliques, or Jumping the Shark, or something in that vein.

Show Me the Place, Twidle’s latest collection, eschews performative confidence in favour of an earnest curiosity about how to inhabit a world that seems to tend ever more towards the incurious. Where his first collection, Firepool: Experiences in an Abnormal World, had a sugar-rush New Journalism shimmer that was compellingly generative in what it placed before you, the pieces in Show Me the Place feel like they operate in a much tighter radius, abjuring the worldly absurd in favour of the minor, the obscure and the personal. In spirit, if not expression, Twidle’s essaying has the careful architecture of Amis, Rattray or Kapuściński. The writing is magnetised by the easily missable, those offramps from the everyday that take you into strange yet knowable places.

In this regard, it feels well suited to a contemporary common mood that has borne witness to the bonfire of certainties. It’s ever more difficult to essay with a clear conscience: the cool, collected marshaling of knowledge that typified many an essay collection released in the past decade risks feeling bogus now. Perhaps the rampant over-saturation of the form’s particular sociolect in recent years, be it let-me-tell-you-what-it-is reportage, or the softer voice of the personal essay, has fatigued some readers to the point where it’s now difficult simply to accept the essay as a social good. While it’s true that there is something compelling in watching someone arrange the wanderings of their thought process in relation to both abstract and everyday things, the essay risks much. There is no assurance that cannot be kneecapped, no confident assertion about the world that won’t see you getting cooked. Look what happened to prime roaster Lauren Oyler when her potage of thoughts and feelings saw the light of day.

In Twidle’s collection (the title is taken from Leonard Cohen), the ordinary is the landscape, to be sure, but constellated with surreal shards of close noticing. The opening essay, a sublime paean to the complex convergence in surfing of joy and peril, tosses in surprising reportorial moments:

A kind of middle-aged enlightenment was dawning, I told him as we pulled off our wetsuits in the car park, keeping an eye on the twerking video being filmed next to us. A woman in a mini skirt bent over the bonnet and did her thing as the latest gqom banger throbbed from inside a BMW. ‘Stop it I like it!’ said the car guard who had been trying to sell us fossilised shark teeth. I began shouting it after a pummeling out to sea: ‘stop it I like it!’

Twidle’s writing favours a tethered kind of digression, ranging informatively away, only to return to the larger subject. Often, this subject is the texture of human peculiarity: each of these nine essays is dense with life in ways that make them utterly compelling. An essay on attending a transformation workshop warps into something quite odd indeed. In a kindred piece, a spell helping out at a hippy-dippy retreat centre invites the reader to bear witness to the calamitous strangeness of an ill-thought-out utopian project. To read these essays is to gain admission to places you might never have thought possible. What, for instance, links a Century City art installation, the late author K Sello Duiker, and a chameleon-protecting activist with Cecil John Rhodes? In ‘To Spite His Face’, a defiantly improbable pursuit-story that whirls around you and flattens out somewhere east of meaning, all is revealed.

It helps that each of these essays is a lesson in how to write with meticulous attention to the run of a sentence. Look at this description: ‘The shoreline slowly resolved: a boatyard, a hotel on the pier. White and grey pebbledash homes with laundry lines outside, clothes snapping in the wind.’ Description is its own creative practice. To describe an encountered scene in a way that evokes the unique music of the moment is a difficult thing to do, which is why many writers ornament their poor efforts with adjective and metaphor. There are times, to be sure, when Twidle slips into the easy higher gear of his many influences:

He wants grandeur, the Romantic sublime, feats of perfection and beauty. He has known them in his youth, and so expects them, hopes for them again. Any success for me would come, if at all, via attrition and doggedness.

A faintly Coetzeean passage like this, with its syncopating clauses and comfort-ridding qualifiers, stands proud because its weighting is leaden compared with the stuff around it. Twidle’s sentence-building is pleasingly supple and free-flowing, which perhaps exaggerates the one or two moments where the text doesn’t lift off. For the overwhelming majority of the time, there’s only a sense of well-honed discipline at work here, and the essays read with a cohesive fluency that belies the inevitably quilted nature of such a book.

The most beautiful of the essays is also the one that defeated my attempt at being its critic: a multi-part gut-punch in which Twidle writes about his mother’s dementia. It’s an excellent, unbearable read that stays with you long afterwards.

The essays in Show Me the Place marshal a campaigning spirit against the bad effects of a society fractured by disagreement over whose version of reality shall obtain. There’s a bracing honesty about the way the book enacts an open-hearted refusal of the atomised world. In this sense, it is doing needful work, by casting a light on how to productively refuse the smoothing, reductive effect of ordinary ways of seeing.

- Editorial Advisory Panel member Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on X.