Thandiwe Ntshinga’s Black Racist Bitch is the sort of book some readers will absolutely love, and others will find unreadable, writes Wamuwi Mbao.

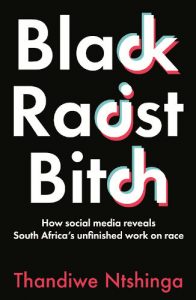

Black Racist Bitch: How Social Media Reveals South Africa’s Unfinished Work on Race

Thandiwe Ntshinga

Tafelberg, 2023

It has become a lamentably immutable South African tradition that a certain kind of white South African will lurk in the corners of social media you and I don’t often frequent. Look for the nostalgia pages, the ones called ‘Memories of Joburg’. Or look at the replies to the news tweets, startlingly inarticulate in their anger. Querulous in their sense of having been wronged, or of having been made irrelevant, which amounts to the same thing. Belligerent at any suggestion that their invective is racist, they are the gang who believe that to point out racism is itself racist.

If they are a barometer of anything, it is that intransigence never knows itself to be such. You’ve seen it. The monosyllabically deluded ‘When-I-Was-Young-Joburg-Was-Clean-Look-At-It-Now’ Facebook grumblers and mumblers, over-invested in a racial identity that hasn’t yet paid out. The right-wing-for-clicks TikTok jesters. The immodest ambient-racism politicians who now happily say in public what was considered only suitable for discreet dinner-table muttering before. What they all have in common is a galling lack of embarrassment. They don’t see themselves in context, which is why they don’t realise that they’re acting white.

The willed inability to see oneself as acting, and being acted upon by, race—one way in which we might define whiteness as a social concept—has a history of critical study in this country, among which Thandiwe Ntshinga’s potently ungoverned book Black Racist Bitch numbers as a new entrant. The work of understanding whiteness and its effects on the world is important, yet it is often regarded with scepticism and impatience by critics (invariably white), who argue that it recentres whiteness, or that it essentialises identity (a lazy argument). Certainly, the vogueish self-reflexive thinking exemplified by white scholars from Antjie Krog and Leon de Kock to Melissa Steyn, who wrote incisively on whiteness two decades ago, has largely fallen away in the South African social science vanguard, even as it has continued to be the focus point of trenchant work by public-facing writers such as Sisonke Msimang, Angelo Fick and the late Eusebius McKaiser.

A cornerstone of Ntshinga’s argument in Black Racist Bitch is that critical whiteness studies is an under-examined field. This is true, in as much as contemporary whiteness is not simply a lingering aftertaste of past privilege. There is much to show that contemporary whiteness reifies itself in virulently toxic new ways that many white people are disinclined to engage robustly. Witness the prevalent nastiness that infects the white body politic: the Helen Zilles, Steve Hofmeyrs, and Afriforum Jeug—mediocrities all—are merely the weepy crust of a general festering. Ntshinga’s book seeks to understand something about whiteness and those who benefit from it, ‘the white South Africans who are always complaining about a societal decay with the strategic purpose of legitimising white governance as well as garnering intellectual and moral support for white domination’. As a graduate of three of the country’s prominent historically white universities, Ntshinga’s academic preoccupation has been white impoverishment, the so-called ‘poor whites’, and their fraught relation to the mythology of whiteness.

Ntshinga begins this punchy tome by outlining what brought her to social anthropology: as a middle-class queer Black womxn, to be interested in the habits and mores of white people is an unusual research area. Yet Black Racist Bitch suggests that there is something instructive to be gained in looking at that which resists being looked at. Clocking in at 178 pages, Ntshinga’s book is a shaggy dog of theory, historical contextualization and memoir narrative, by turns untidy and compellingly propulsive. It’s a work composed to the beat of digital media, and this is both a strength and a weakness.

Its weaknesses, simply expressed, are a digressive formlessness, a peripatetic musing that never settles long enough for the reader to find their footing. In one section, we move from the author’s time at various historically white universities (helpful for contextualising the interest in whiteness), to a discussion of ‘transnational interracial queer dating’, alighting there very briefly before moving on to the kindred subject of being friends with white people (also a subject that perhaps merits longer discussion than the desultorily anecdotal treatment it receives here). Time and again, the reader encounters a bracingly lucid passage, a thought that begs following, only for the trail to peter out in an unfamiliar thicket.

For instance, at one point in the book, there is a disquisition on South Africa’s history of raced relations that parses where elucidation is called for, rehearses the tenets of Patric Tariq Mellet’s The Lie of 1652 (an excellent work, stitched in here to no great benefit), and somehow manages to make several unfortunately reductive and anachronistically awful points about ‘coloured identity’. The line of argument is too often below the book’s waterline, leaving the reader to speculate haplessly on what might tie several interesting but ultimately disjointed tranches of narrative together, beyond their anecdotal interest.

At other points, there are slippages that frustrate. Sindiwe Magona is many things, but she is not a ‘critical race scholar and practitioner’, as is implied at one point late in the book. The section where this minor faux pas occurs is one in which Ntshinga is astutely relaying the laughably predictable wailing and gnashing of white parental teeth that ensued when a Western Cape school brought in a diversity trainer, after a teacher had unfeelingly used the so-called K-word while reading Fiela se Kind to a diversely constituted class of students. It’s the kind of racist banality that conveys much about a school and what black children will experience when they attend it. This is an interesting case study, dulled to pablum by its being rendered in an exhausting stream of reported speech.

I point out these glitches only because they snag at the sleeves of what is an otherwise discursively intriguing book, one that throws knowledge, feeling and event, and voluble analysis at the social maw of whiteness in an attempt to arrest its insatiable centering presumptions. Indeed, the intellectual work that Ntshinga has done to bring critical whiteness studies to TikTok, that most deliberately transient of social media platforms, is a fascinating topic, the labour behind which is viscerally illustrated in the exchanges Ntshinga has in the comments sections:

@Adam Morel black people are just as racist as white people, just saying.

@Black Blah Just say you’re racist and move on.

@user3087017988102 Niklas The real racist is the one pulling the race card.

@blackwomxnrants Ohhhh, I really wish I knew where this miseducation comes from. It doesn’t work like that … that’s not how racism works.

Black Racist Bitch captures much of the foetid squalling of the world’s comments sections, an endless dialogue of vomited opinions spewed by dim-wittedly unhearing white people. Whether there need be quite so much of it in this slim book when it isn’t clear if this is the focal point of the narrative is debatable. It should certainly be no surprise that racist white people are systemically invested in not seeing their racism everywhere they go, including the virtual world. But Ntshinga’s argument is of course a more complex one, namely that the relentlessness of it demonstrates just how little was conceded, and how even that concession is stolen back shamelessly as whiteness continues to privilege and embolden its own.

When a book flails about without the boundaries of form to pen it in, it risks doing damage to its own project. Black Racist Bitch is confounding because it isn’t sure of where it wants its centre to be. The fire-alarm provocation of the title leads one to expect a resolution that isn’t quite there. Perhaps there is too much to be said about whiteness and its pathologies. Some readers will absolutely love the treatment they’re given here, others will find the book unreadable.

- Editorial Advisory Panel member Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on Twitter.