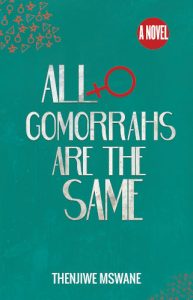

The JRB presents an exclusive excerpt from All Gomorrahs Are The Same, the debut novel from Thenjiwe Mswane.

All Gomorrahs Are The Same

Thenjiwe Mswane

BlackBird Books, 2021

Read the excerpt:

1

Thulani

We did not bury my daughter.

~

My mother does not remember how old she was when she buried the first of her children.

~

I have not yet buried a child. I have waited on that door every day from the day she left.

She left a long time ago. Perhaps it was the day we forced her to grow too fast. The day of her first day at crèche. She was too young to start crèche.

Then she was too young to go to Class 1, but she did. Her mother applauded. She received it. Worked harder. My daughter was learning how to leave from her first day in school.

By the time her body left—disappeared—from all our lives, she had been missing to herself for a long time. I watched my daughter leave.

2

Makhosazane

My siblings and I spend every holiday eMpofana, Mooi River, KwaZulu-Natal. Right in the middle of the Midlands Meander.

There is me, Makhosazane, and my two brothers, Mpumelelo and Nkosana. My brothers are older than me and have started to show signs of growing less and less interested in this place.

Mpumelelo only started packing an hour before we were due to leave. uBaba became his angry self, which is speaking words under his breath. I always imagine the swear words, because why doesn’t he say them out loud, properly? Mpumelelo has taken to responding under his breath too. It is like watching a whisper fight.

Mpumelelo was looking for the wardrobe key under the bed. The space between the wardrobe and the bed was too small for him to bend down properly and look. He tried anyway, turning half his body against the wardrobe, his arm not getting far enough under the bed. I knelt at the bottom of the bed; moving the shoes, lost socks and balls of ‘bhoning socks’ around.

Mpumelelo was still whisper fighting with uBaba.

‘Angazi nje ngiyokwenzani mina laphayana,’ he whispered.

I looked back and saw uBaba still impatiently standing by the door, peeking over at Mpumelelo, who was barely trying.

‘Found it!’ I screamed, jumping up and giving Mpumelelo the key.

He opened the wardrobe and started throwing clothes into his school bag. Nowhere close to enough clothes; but I didn’t care. All I wanted was for him to be packed, and ready. I knew both him and Nkosana wanted to stay behind to play iTV game; which I thought ridiculous because they play that thing too much. It was not helpful that uGogo didn’t allow them to play it at her house. Complained it broke her TV.

There are more than twenty of us here during school holidays. There is no way of regulating who plays Sonic the Hedgehog, or when. Still, they tried to play, stealing the TV game from where they hid it, under the heaps of unfolded clothes that were still in their bags a few days after we arrived. Ikamera labafana is always dirtier; uGogo doesn’t go in there as often to shout at them about packing and unpacking. I have to share the bed with her, so I can’t escape unpacking. I unpacked on my first day. The only thing hidden under my heaps of neatly folded shirts and shorts is shoes. My favourite shoes, which I will wear on the day I leave so no one can borrow them. I don’t want everyone to know I have them. That way there is never any fight.

Gogo was away that day, it was the day of impesheni, and she would be back late. The TV game playing ended in some fight I didn’t care for. Which was one of the reasons uGogo hated that thing. They always ended up fighting.

Me, I prefer sitting at the top of the hills and mountains. Looking down on iMpofana. They are endless, the hills and mountains. From up there you can see streams, rivers, stagnant waters, and the footpaths in between the hills and mountains.

There is a not so big road in the middle of the valley. You can see it clearly, sitting at the top of a hill. The road comes down from a hill too; you cannot see the other side of the road because of how steep it is. The road has slight turns and bends before it disappears again at the far end, behind more mountains and hills. Most of amakhumbi and cars stop only on the main road. Estopini.

uMkhulu’s house is on an old farm, although we call it kwaGogo. I only knew it was uMkhulu’s house because he told us often—‘this was the same farm where my father, and his father before him lived.’ Iplazi. Although the fence that once showed it was iplazi had been taken down. So it was less iplazi and more amakhaya. Even though everyone eWembezi says we are going emaplazini when we go there. So maybe it was both, because it had been iplazi.

‘Wazimoshela yena umfana kaGraham, kwakungonakele lutho.’

My grandfather would recite the story of how his grandfather had lived there and there was no fence. The son of Graham then built a fence. They had bought the land, Graham said. Which made no sense, because he couldn’t buy the land. Land belonged to everyone and was fairly distributed by izinduna.

Yes, some people had started working for the Makhulu Graham, but not everyone wanted to work for Graham after Makhulu Graham died. The young Graham was known to be a cruel young boy, ‘unlike his father,’ uMkhulu said.

So many people were angry when Graham said he had bought everything, and that it was his farm. No one was forced to work for him, but if you did not, you had to give him a cow every year as intela. Even then people did not understand and many did not give him their cows. Eventually Graham and the other men from Mooi River came to make isimemezelo. They even had a person to tolika, that uhulumeni was going to come and make sure everyone paid intela. Five cows, because many people were behind and still owed uGraham. uMkhulu said the people laughed at Graham’s friends and uhulumeni. Then one day, Graham’s friends came again. This time they said all their cows had diseases and needed to be killed. This made the community angry so, that very night, they tore down Graham’s fence and put it outside his house.

No one went to the meetings at Graham’s house after that. There was no longer iplazi without the fence. ‘What even are fences?’ uMkhulu would laugh.

Graham’s friends tried coming to each household to find out who had taken down the fence. Sabakhathaza, uMkhulu would say. Told them every structure was its own household. Giving them more work to do. The tolika tried to argue with them, but he was from kwaNongoma. So they remained firm, izinkolo azifani. Nongoma had its own izinduna, amakhosi and even amasiko, which was true.

In every second ‘house’, there would be no man—because it was either the kitchen or a bedroom. In those ‘houses’, the women listened and listened to the tolika. Asked many questions. Asked for more and more clarity, only to say later, ‘Well, we hear what you are saying. We do not understand. But it is not ours to understand, anyway. The head of the house is not here, as you can see. You are speaking about our house. And our house is headed by him. Come back another day to tell him.’

Mkhulu said the friends tried coming back again and again. Bringing Graham with them this time. Then they went into the house of inyanga, who cursed Graham.

Graham died, and his wife was left alone. Mkhulu said they sang outside her house every night for a month, claiming they were helping her mourn. She got scared and left. That was the end of it being a farm, iplazi. After Graham died, the village banned fences.

Fences make people think they can own not only things, but lands and people too, the village decided. So there was no clear separation of a ‘yard’.

But you can still see the different yards, especially from up here on my hilltop. Our yard looks like many other yards on the old farm. There is a main house, ilawu, which is where abakhwenyana sleep when they are here. Only for the week before Christmas. Each mkhwenyana arrives with a car boot filled with food, and they shower us with money and sweets. Big meals are made for them. After Christmas, on Boxing Day they leave. The end of Christmas, almost the new year. No more showers of money. Almost school time.

Our yard also has a few rondavels, and a cemetery just near the apple trees. Sacred land. We seldom play there. The only time we enter there is when trying to pick apples. The dark green sour-tasting ones grow there mostly. No one told us not to play there. Just sacred land, we all seemed to know.

There are thirteen graves in the cemetery. Most of my cousins’ parents now lay on that ground. I wonder what it feels like to grow up knowing your parents are in the same yard but can’t ever come to your rescue. Christmas must be the worst, when someone has stolen your money, which my older boy cousins do. A lot. Those of us who can, run to our fathers, who will shower us with money again. My cousins run to my grandmother, who turns to uMa to give her money. They tried hiding this exchange when we were younger, but the older we grew, we knew things. Saw things. The one time, my other cousin Njabulo teased uEnhle, saying it was still his money because his mother gave uGogo the money, and his mother’s money was his money. Mamncane Thandaza, Njabulo’s mother, was the first to land a slap across Njabulo’s face. She later hugged Njabulo, after he had performed a dramatic cry. Nobody hugged Enhle.

uMalume omncane uMgedeza, one of my uncles, is not buried here. He requested to be buried in the local cemetery in town. The sign from the main road says ‘Mooi River’ 37 km, Giant’s Castle 15 km. uMkhulu was not happy with this. I remember Ma convincing him that this was what uMalume wanted. That it was his wishes, and they needed to be respected. It was still far, uMkhulu insisted, but uMa gathered her mother and sisters to rally behind her and uMkhulu was outnumbered. Although I always thought he was right. It was far on the day of the funeral, and it was far after the funeral, when we had to go fetch him from many places and bring him back home with ihlahla. I don’t know why no one ever listened to uMkhulu, even my cousins sometimes didn’t listen to him; or they talked back, which I would never do. He was old, and wise, and had many children. Of the thirteen graves in our yard, six of the graves were his children and he still had more. The adults always insisted there were other children. Five more.

~~~

- Thenjiwe Mswane holds a Masters in Anthropology. She is currently doing a PhD with SWOP (Society, Work and Politics Institute) at Wits University. Mswane is an experienced Gender Researcher, and a retired Queer Activist.

Publisher information

This epic tale is narrated through the eyes of three women.

Makhosi, who seems to be angry with the world and unable to find the language to make her mother, and sister understand her ‘anger’.

Duduzile, Makhosi’s mother. A working-class mother who feels herself lose touch with her daughter.

Nonhle, Makhosi’s younger sister, who watches her sister grow while the gap between her sister and mother widen and them continuously miss each other.

This story lets the reader into the very complicated generational conversations within black families on a varying a range of issues, womanhood, parenting, sexuality, sexual abuse and most importantly, mental health, addiction and loss.

Is this a heavy read? Yes! But it is also the most enlightening read you will come across this year.

Hi where do we get a copy of the book?