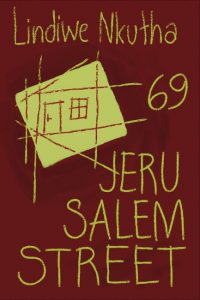

The JRB presents an excerpt from the title story of 69 Jerusalem Street, the debut collection of short fiction by Lindiwe Nkutha.

69 Jerusalem Street

Lindiwe Nkutha

Modjaji Books, 2021

~~~

69 Jerusalem Street

Even the semi-senile in our township knew what month it was, thanks to the ever-present, back-to-back dust volcano eruptions, prancing about as if to a tune played by an arthritic fiddler. August was the month of this spectacle. Whirlwinds came, and like ice skaters, twirled themselves to dizzying frenzies then stopped seconds before blowing everyone away.

I was again reminded, by the whirlwinds of August 9, 1997, that August winds, unlike those of other months, always came armed with a purpose. Four to be exact: shooing children weaving memories off the streets; clearing the same streets of limping three-legged dogs with decaying teeth; applying a layer of crimson on the baby nappies lynched in the yet-to-heat-up spring sun, and plummeting women into a swamp of unrelenting pain. August. That majestic month set aside for the celebration of women.

‘Trust them to give us a dirty month,’ my mother said. August, more than any other month, was notorious for its effect on the senses. So much so that it came to live in most women’s minds as the vision and smell of a cheery but appalling man with two bags of sliced onions hanging from his armpits.

All of August’s days were cruel, but for our reprieve. Saturdays seemed a bit merciful, even though that mercy came at a price. The price being our steadfast adherence to established routines. Any form of deviation from which, however small, was met with the harshest chastisement.

Ours were very simple routines, and as such, ones from which it was almost impossible to deviate. That was until Rasputin Moferefere Kgosana, without consulting anyone, decided to veer away from them and by so doing earned us August’s fury. Another way of looking at it—and this observation is a gift delivered by hindsight—is that even before this Saturday, he had always lived amongst us as August’s wrath manifest, but had been biding time until that hour, on that Saturday, to reveal himself fully.

Our Saturdays began, always, with a breakfast of magwinya, snoekfish, whatcliver and atchar. Young girls with towels wrapped around their waists grudgingly swept their mothers’ yards, rivalling the whirlwinds with the number of dust storms they raised. Some men left their houses for work and some for heaven knows where, to return later the same day. For others, the same hour the next day, if at all. Women with pegs dangling from their pinafores and their young on their backs busied themselves with the week’s washing and giving their stoeps a shine so bright it could easily be confused for the sun’s beam.

A half-drunk neighbour, still smelling of sleep, strolled over to anyone’s fence to talk about the party they had attended the night before. The local priest took a more than ample swig of the blood of Christ, and confused himself about which event to attend first: the funeral or the wedding. A young bride in two minds caught sight of her image in a three-way dressing table mirror and wondered which of her now four selves she would still recognise a few years down the aisle. Cupboards were checked for vanilla essence ahead of the day’s anticipated baking. Ausi Sinah and her friends, MaPatronella and Sis’ Nomonde, made their way out of their houses to ours to sit on the stoep as they had done every Saturday without fail. ‘The Township’s Trinity’, as everyone called them, to avoid calling each by name. Their friendship so old none of them remembered its beginnings.

As far as I can remember, our mornings repeated themselves like this for the 468 Saturdays I had been alive. The afternoons, too, were consistent. They entailed the return of the men called responsible from work or heaven knows where, to the townships but never to their homes. These would be the same men who had left work, or heaven knows where, at about one o’clock, to congregate at around two at the many shebeens that peppered our township. This, so that they could begin the worship of two of the most sacrosanct Saturday deities, for which shebeens were consecrated sanctuaries: beer and football. Shortly before three, they would make themselves comfortable enough to paste their eyes on the screens that would deliver them their weekly dose of a tension-rousing showdown between victory and loss. Shebeen queens would also ready themselves to charge for beers, both consumed and not. Then the man behind the screen, in the black and white shorts, would blow his whistle and declare the battle commenced.

No one had different expectations for this Saturday which, until half-past three, was rolling out very much like any other before.

Ausi Sinah and her friends had finished baking the scones they would swallow with bits of gossip as they sat on the stoep. Ausi Sinah was our landlady and owner of house number 69 Jerusalem Street, the biggest house in all of Phomolong. She was the youngest of the three friends and being this side of fifty, they called her ‘Maiden’. Although she herself had done precious little to preserve her youthful looks, life and gravity had been very kind to her. She rivalled in agility and good looks many women younger than herself. Looking at her standing next to my mother, one could swear that she was the younger of the two. This, even though my mother was actually fifteen years her junior in earth years. However, my mother was at least a hundred years Ausi Sinah’s senior in life experiences.

Slightly older than Ausi Sinah, was Sis’ Nomonde, who cut a figure reminiscent of Mary, Mother of God but which time’s passage had sadly done its fair share to deconsecrate. In the end she looked just like anyone’s mother. What she had lost in her pious looks, though, she had more than made up for with the air she exuded, which she must have inherited from a long lineage of women before her. MaPatronella, the crone, was the eldest and thinnest of them all. Beneath the carpet of her now completely greyed hair she carried the wisdom of four sages. A close look at her hair always had me imagining that an intent baker had dusted her head with particles of icing sugar to give her, her sweet disposition.

Number 69 Jerusalem Street was a space that three families called home. My mother, Ntando; Rasputin Moferefere Kgosana, her husband and ostensibly my father; and myself lived in its garage, a self-contained home in and of itself. MaPatronella had recently moved into one of the backrooms after her children finally managed to tell her in no uncertain terms, that they no longer had room for her in what used to be her house, and their hearts.

Ausi Sinah lived in the main house.

She had extended the house from its matchbox beginnings, using the small fortune she had amassed through means best left undiscussed. The stoep, however, had always been there. The only alteration that had been made was to extend its width to accommodate the friends’ girths which had expanded over the years. She had given the rest of the house big windows so that she could steal herself a lot more yellow sunlight and stir green envy amongst her neighbours, all in one stroke. For good measure, she had built two back rooms and a garage, which, as I have said already, she rented out to her friend and my family. She was entrepreneurial. For her, 69 Jerusalem Street was a small section of earth she took pride in calling her own.

On this particular Saturday, the men in the shebeens were slowly losing their sobriety. There was already so much dust that the women had long given up cursing it for soiling their washing. Rasputin, who had also left in the morning as part of the menfolk’s exodus—the section that had left for heaven knows where—was making his way back. He was coming back home. To our house. On a Saturday afternoon! He had never done that before. None of the men in Phomolong did that. He was varying our routines and August would not be pleased.

~~~

- Lindiwe Nkutha’s short stories and poems have appeared in a number of journals and anthologies such as Queer Africa, Chimurenga and Itch. She is an accountant who keeps kindled inside her heart the fire to tell stories. She was born and raised in Soweto and now lives in Johannesburg with her wife Lerato, surrounded by their capricious veggie and herb garden.

Publisher information

‘Each story here has the velocity and voluptuous fullness of a novella, or a street corner epic banter. The writing is a flourish of (unpretentious) philosophical gravity, leavened with every day dialogue, and accessible beauty. This is an imaginative collection that sets fire to the confines of genre: It is both poetry and prose. It is all the richer for this. Unorthodox, and ultimately alive.’—Bongani Madondo

‘A fine, heartwarming collection of stories that reveals the nuance of women in townships in dignified, elegant, prose. Lindiwe Nkutha tells stories about women kokasi without falling into stereotypes and clichés. She has humanised where I come from and my people, for that, I thank her.’—Welcome Lishivha

In her debut collection of short stories, Lindiwe Nkutha takes us through the minds of people you may overlook on an ordinary day: The wayward neighbour you vaguely remember seeing every day as a child until the day he vanished. The face you see every weekend at the local drinking hole, you exchange a polite nod but know little about, not even her name. The young woman who is caught between her faith and her love for a woman. Their lives are untidy, tainted with the pain, joy and violence as they share with us stories they wouldn’t share with anyone else.

Nkutha’s words weave in and around the weights we drag behind us from one place to another, with a sensitivity and wit required for such vulnerabilities and intimate moments.

Congratulations, Lindiwe! Looking forward to the book.