Zanta Nkumane reviews Ocean Vuong’s The Emperor of Gladness, a novel not intent on building a new national myth, but mourning the debris of the old one.

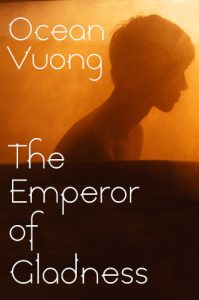

The Emperor of Gladness

Ocean Vuong

Jonathan Cape, 2025

The American dream is dead. Or perhaps, for those forced to chase it from the margins, it was never truly alive. The concept has always been a promise that feels like a punishment, and the dissonance between myth and lived reality lies at the heart of Ocean Vuong’s work.

In his debut novel, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Vuong explored the brutal tenderness of growing up queer, poor and Vietnamese in a country that demands assimilation while withholding a sense of belonging. The Emperor of Gladness feels like its haunted continuation, in which Vuong confronts the emotional wreckage of those who are told they should feel grateful for coming to America, and yet are slowly being unmade by the very systems that promised them salvation.

The novel opens on the edge of a bridge, where 19-year-old Hai, a Vietnamese immigrant, is contemplating ending his life. His suicidal impulse is not just personal but political, a response to the suffocating weight of economic insecurity, the impossible burden of expectation and his own failures to fulfil the bright promises of life in a new country. His descent from the ledge is interrupted by 82-year-old Grazina, a Lithuanian widow with dementia, whose unexpected intervention leads to an unlikely relationship. Grazina asks him to stay and take care of her. Together, they navigate a form of survival shaped by ageing, migration and systemic invisibility in the fictional town of East Gladness, Connecticut.

Life should be open and full of possibility for Hai, whereas for Grazina, the world has shrunk and is fading towards death. Initially, this generational divide seems insurmountable, but Vuong uses the contrast to illustrate the loneliness experienced by those who are forgotten in America. Despite being at opposite ends of life, the two characters are bound by a sense of isolation, and this becomes a conduit for a portrayal of care and unexpected family. A significant part of their relationship involves managing Grazina’s dementia, which is more than a personal condition, becoming a narrative device. There are moments where it appears to hinder her experience of reality, and Hai comes up with a method to determine whether she is having an episode, asking her: ‘Who is the president?’ It’s 2009, so it’s Obama. Yet Grazina’s affliction allows her to escape time, memory, perhaps even capitalism. Rather than being solely tragic, there is an underlying sense of liberation to her condition, which breathes an unsettling hope into the suffocating emotional landscape. In a country that has long forgotten her, Grazina’s forgetting becomes a quiet rebellion. It is as if she is rejecting the demand to remember a nation that has erased her. Her condition becomes a ‘screw you’ to the American state and its unequal mathematics of usefulness and productivity. Vuong doesn’t romanticise her illness, but he does leave space for the possibility that in the absence of memory there may also be relief.

Meanwhile, Hai, an opioid user who is hiding the truth from his mother by pretending to be at medical school, finds work at the Home Market, which serves as a representation of exploitative low-wage retail. He uses his cousin Sony as an in to get the job, and it is here that his social circle expands. We are introduced to a slew of characters: BJ, the manager, an amateur wrestler; Maureen, a cashier who uses frozen mac and cheese to soothe her arthritic knees; Wayne, the barbecue expert; and Russia, a boy who is paying for his sister’s rehab. Each person is navigating the American dream in their own way, trying to get by. This improvised family reflects Armistead Maupin’s concept of the ‘logical family’: the idea that, for many queer and marginalised people, survival necessitates forming chosen bonds when biological or state structures fail. For Hai, the Home Market becomes more of an emotional refuge than a job, a place where shared struggles give way to acts of care and humour. This kinship is not based on blood but on the recognition of stalled mobility. By transforming the workplace into a home, Vuong challenges the concept of the ladder of success and the traditionally impersonal nature of the work environment.

Hai’s new friends defy the myth of transcendence promised by the American dream: if you work hard and live right you will be materially rewarded. At the Home Market, people work long hours for minimum wage, enduring exploitation and invisibility, only to find themselves trapped in a cycle of precarity. Their ordinary lives reveal how the promise of upward mobility does not apply equally to everyone in this good America. It simply wasn’t designed to include certain people. Despite this, they continue to dream: BJ aspires to become a professional wrestler, while Wayne harbours ambitions of opening his own barbecue joint. Hope is a currency of survival that almost mitigates the harshness of their realities. Is this a fair exchange? Absolutely not. Hope without a changed reality is no reward, it is merely a coping mechanism.

It was, however, through this constellation of personalities that I noticed how Vuong’s characters often speak with a lyrical omniscience, as if suffering had fast-tracked them into wisdom. Their knowing tone conveys an emotional clarity bruised with insight. While this aligns with Vuong’s literary style, it can also flatten the novel’s voices, making it sound as if everyone has already processed their trauma. This may unintentionally reinforce the myth that struggle produces fortitude; that pain somehow refines us into philosophers. But not all suffering leads to clarity. Vuong’s gift for language can obscure the fact that many people do not emerge from hardship more enlightened, just tired.

Alternatively, knowingness may not signal superiority, but rather an assertion that even the most marginalised lives are rich with insight and contradiction. This focus on internal complexity could have become a means of restoring dignity to people often overlooked by the American novel and America itself. However, here it feels like an extension of Vuong’s ego, a projection of his life wisdom onto characters who, given their social and emotional constraints, are not likely to possess such articulation. At times, their contradictions fail to shape them and they merely serve as vessels for his reflections. (I suppose a novel is a body of the writer’s reflections, though?) While it is clear Vuong is attempting to dignify the marginalised by giving them depth, he also occasionally romanticises their pain through an autobiographical lens.

In The Emperor of Gladness, transcendence is not always as liberating as anticipated. We experience this through Grazina’s son, Lucas. He appears to have achieved a semblance of the American dream: he lives on an estate with his wife and two children, leading an archetypal middle-class, white-picket-fence life. However, when Hai and Grazina visit for Christmas eve, Lucas’s children say Grazina smells like urine and are generally rude. Lucas doesn’t intervene in any meaningful way, and his overall coldness makes success feel less like a triumph and more like a trade-off. It appears that, for him, material freedom has meant severing cultural and communal ties; that upward mobility alters our relationship to memory, to responsibility. Lucas is a site of transcendence but also represents its unspoken cost; that the American dream only measures success in material terms.

I am not interested in critiques that question Vuong’s use of language or his linguistic choices. White writers are usually not challenged about their linguistic authority. When white writers are anti-form or curl English into abstraction, they tend to be praised rather than questioned, because it is a language they ‘own’. Non-white writers, however, are burdened with the racialised expectation of explaining their meaning. Perhaps Vuong’s lyrical use of language is considered suspect because, in part, it refuses to perform clarity for the dominant white gaze. These critiques are not about craft, they are about ownership. What I am interested in, however, is how Vuong writes about Vietnam and Vietnamese identity. Like Vuong, Hai is Vietnamese and appears to speak Vietnamese with his mother. However, in the book, the conversations are offered in English, with Vietnamese showing up only sporadically. This technique is common among diasporic writers, who exist within the tension of maintaining cultural and linguistic authenticity in a predominantly English-speaking global literary marketplace. As a writer from the diaspora, Vuong’s work provides an opportunity to discuss what it means to write about Vietnam, in America, for a Western, often white, literary audience.

The writer Som-Mai Nguyen has criticised Vuong for flattening Vietnam and Vietnamese identity into metaphor. Nguyen presents a compelling argument, suggesting that Vuong’s Vietnam is often less a real place and more a poetic device, mediated by distance, trauma and familial storytelling. But Vuong’s diasporic romanticism is understandable. It stems from a visceral longing for a home that is more imagined than real, since America functions more as a host than it does a home for him and his characters. While his approach appears to be an act of healing, it is also devastatingly limiting. It is burdened by his location within the American literary market, and the accompanying pressures of visibility and legibility. That Vuong is not a Western outsider per se further deepens this tension, as his role as a ‘translator’ of Vietnamese memory for largely Western audiences risks reinscribing certain Orientalist tendencies. As Edward Said argued, the power to represent is never innocent. It is shaped by the histories of empire and the mechanics of who is seen, who speaks, and for whom. Vuong’s positionality complicates his role. In rendering Vietnam as a place of suffering or poetic abstraction, Vuong risks reproducing the East as a monolith rather than a complex, living reality. While I am not disputing his right to remember, I am highlighting how his version of Vietnam is shaped by his circumstances and his audience.

Another tension in Vuong’s work is his refusal to fully claim that parts of him are American. This shapes the limits of his vision; by turning away from America as part of the self, the empire within, he externalises it. Viewing America, the country in which he grew up, which shaped his worldview and granted him Western access, solely as a site of violence and never as a conflicted home is a disservice and an oversimplification. Vuong’s unwillingness to fully inhabit America may protect the wound, but it also leaves important truths unexplored.

If we are to read The Emperor of Gladness as an ‘American novel’, we should also note that Vuong does not so much radically reshape the genre as write within it. His America is grief-soaked, full of ghosts and drugs, but it is rarely complex or contradictory. Similarly, his Vietnam is less a nation than a symbol, more a longing than a reality. In refusing Americanness and idealising his homeland, Vuong risks diminishing both. Yet perhaps that is the point. Perhaps Vuong is not intent on building a new national myth. He is mourning the debris of the old one. His novels don’t propose solutions; they give us language for what remains when dreams collapse.

~~~

- Zanta Nkumane is a writer and journalist from Eswatini. His work has appeared in the Mail & Guardian, OkayAfrica, This Is Africa, Lolwe, Racebaitr, Amaka Studio, The Johannesburg Review of Books, Kalahari Review and The Republic & Michigan Quarterly Review. He was a Short Story Day Africa Inkubator Fellow 2022/23. Zanta was the 2022/23 UEA Booker Prize Foundation Scholar in the MA in Creative Writing, University of East Anglia.

This is such a thoughtful and layered review, one that holds Vuong’s brilliance and his blind spots in the same hand. I appreciate how you refuse to let the lyricism distract from the structural questions: who gets to speak, for whom, and with what consequences. The observation about Grazina’s forgetting as a quiet rebellion struck me deeply, it’s a rare and necessary framing that resists the urge to sentimentalize.

Your critique of Vuong’s positionality in writing Vietnam for a Western audience also feels urgent. As someone from a marginalized community, I know how tempting it can be to render home as metaphor when its material reality is fragmented, but you’re right: representation is never neutral, and audience shapes the work as much as memory does.

Perhaps what I value most here is your refusal to demand resolution, like Vuong’s own work, your review lingers in the contradictions, allowing us to wrestle with the tension between longing and legibility, grief and gaze. It left me with the uneasy but necessary question: how do we tell the truth about where we come from without flattening it for where we are?