The JRB presents an excerpt from Your History with Me: The Films of Penny Siopis, edited by Sarah Nuttall.

Your History with Me: The Films of Penny Siopis

Edited by Sarah Nuttall

Duke University Press, 2024

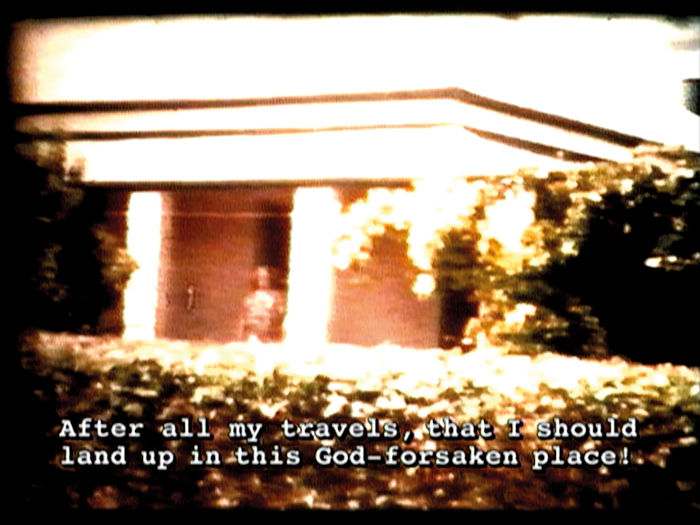

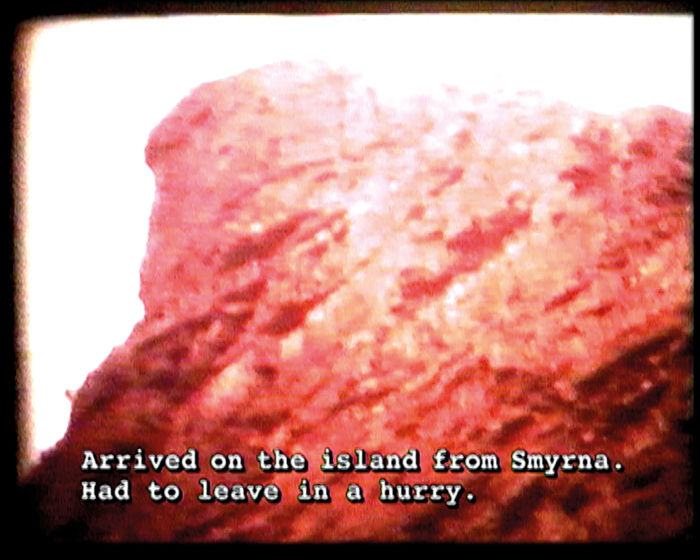

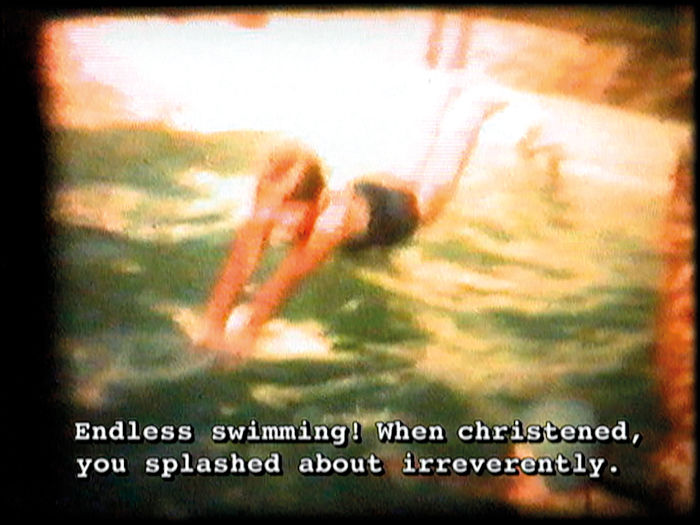

Image stills credit: Penny Siopis, ‘My Lovely Day’, 1997. Single-channel digital film, sound. Duration 21 min 15 sec. Copyright the artist, courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town, Johannesburg and Amsterdam.

Read the excerpt:

It

Will Always

Be You

William Kentridge

It gave me a lot of pleasure relooking at all your films and watching Shadow Shame Again for the first time. It was a treat.

Nine points came to me, and I’ll talk about each of them for a short bit.

Mostly, they’re things I find remarkable about what your films do as films, as cinema. The politics of the films is important—South African, race and gender politics—but my thoughts focused on you as an artist, a craftsperson working with this medium, and what the medium does, the new things you’ve done.

My first thought—many of my thoughts return to this, actually—is about sound and image: the way the sound makes you see something differently and the image makes you hear something differently. In Shadow Shame Again, right at the beginning, there’s an astonishing piece of sound. It’s not clear if it is wolf whistles or birdcalls—it seems to shift from one to the other. I think it’s because of the non-relation of sound to image. This makes one open to what the sound could be, because all of these things are in it, as an unspoken or unsolvable riddle of image and sound. This makes the viewer active and complicit, unable to stop themselves from trying to make connections, finding echoes. And I think that’s one of the remarkable things about the films, the way they turn the viewer into an active sense-maker, like it or not.

My second thought is about images gaining new meaning because of the broader context of the film. A lot of them are very, as it were, ‘innocent’ images found in home movies, which then gain a whole other meaning. A child’s dropped shoe on the ground suddenly becomes the abandoned shoe of someone fleeing from an attacker. Or the shoe that’s dropped from the woman who’s hanging from the tree. If you’d actually had the woman’s shoe shown on the ground, it might be moving or shocking but it wouldn’t involve the viewer in the same way. In Verwoerd Speaks: 1966 you have Verwoerd’s speech but you have a beat that’s drumming behind his words the whole time, which, again, is a kind of brilliant surprise. One of the things it does is undermine his speech, and it does this in that you think he’s trying to make a speech but really next door there’s a party going on. It’s a bit like Donald Trump making a speech, or Rudolph Giuliani speaking at the Four Seasons Garden Center instead of the hotel. It slightly deflates the power of it. And I think it both has the echo of a threat of the ‘other Africa’ that is there outside, that he is apparently ‘protecting’ people from, and there’s a sweetness: this is one voice, but there’s a whole other world going on as well. And there are other images and word surprises. I’m trying to remember what was being sung or said; maybe nothing was being sung. When the children are playing ring-a-ring-a-rosies in the veld, and jumping over the sprinklers, I wrote that down—‘image word surprises’—in my notes. I can’t remember what the words were exactly.

In She Breathes Water, and this is my third observation, there’s also something that happens in the disjunction between a close sound and a distant image. So you have a truck driving with a cloud of dust behind it, and in front you have what I only later read is the sound of ice cracking in the Antarctic, a very present sound. This present sound against this distant image—I would be hard pressed to say what it does, but it makes you alert. It makes you see the image in a different way than if the sound was just of a truck driving along a road or a landscape. You have a sense that there are two worlds happening—there’s a world that you’re seeing in the distance, and there’s something you’re missing very close to you, like that sound—I thought, oh, it’s someone breaking ice in a glass or something. You get this even more with The New Parthenon, where there’s this disjunction with the song and words, in not knowing whether what’s being sung is translating into the subtitles. Also in My Lovely Day, there are words saying one thing while you’re seeing another thing—image and text completely at right angles. You can’t rest. The fact that it’s found footage also gives it a different power than if you said, well, I’m filming something and I’m deliberately going to put the wrong sound against it.

Next is a point about the strange position of the viewer in several of the films. There is a ‘you’ in it, and sometimes the ‘you’ is you as filmmaker, or your grandmother or your aunt talking to you. But often one feels the ‘you’ as you the viewer, that the ‘you’ is me. Sometimes it’s you and your mother, then you as viewer suddenly think, oh, I’ve got a deep connection to this person, I didn’t realize, it’s the mother, oh, OK.

My fifth observation relates to the series of films as a self-portrait in long form. The interesting thing is that you set the agenda in your first film, My Lovely Day. The question of being in Greece or in South Africa. The question of what was happening in South Africa and of women—your mother, your aunt, your grandmother. It’s like a manifesto; one often finds that, without thinking or realizing it, one is making a manifesto. The first work in a series encapsulates so many of the themes that then get expanded in other parts of the series. So for me, relooking at that film again this afternoon, I suddenly thought: yes, it’s all kind of there, you’re setting yourself; these are the things that constitute you—politics, art-making, being between Greece and South Africa, and the politics of being a woman.

The you is there.

The intriguing thing is the way in which the medium of film, the material of film, becomes a way of thinking about the questions or the topics which have been set out in that first film. So it’s almost as if you have a topic of madness and political violence with David Pratt and Demitrios Tsafendas, or being caught between ancient Greek history and the contemporary world. And then you’re able to do the thinking about it in the medium of film rather than having thought about it and then illustrated it in film. So, for example, the voice of Pratt in The Master Is Drowning. Pratt says he had seizures, ‘Grand mal / Petit mal.’ And what you see is the most astonishing evocation of this in film, in the sprocket holes, the burning of the film, the scratches. And it is such a fantastic image of a brain storm, of things exploding in the brain, as if there’s a logic in film and you can represent the break in that logic in all the burning of the footage, in the scratches on the film, in the jumps across. And it becomes the medium of thinking. So it’s important that it’s not understood as a medium of illustrating a thought. The things that one can say about the themes come out of the film, rather than the film being used to illustrate another idea.

My sixth thought develops my sense, watching your films, of the paradox of what it was for you and me to grow up in South Africa. It’s the kind of domestic Elysium of which your grandmother accuses you in My Lovely Day, the accusation of living a ‘charmed life.’ But so many home movies are of those moments, those short fragments of kids doing cartwheels, running around the garden, jumping over sprinklers, playing ring-a-ring-a-rosies. And to say this is one of the things that constitutes what that life was, and then what the films obviously show are all the limits, the protection and walls that have to be built for that to be possible, whether it’s domestic helpers, those who are not in the film, at the edge of the film. This starts to change with some of the more recent films, starts to change a lot. It’s white people primarily who are seen in the early films, and it becomes a much wider range of people in the later films. And that feels completely appropriate, in their progression outward. Also, I think there’s that shift and change when you’re talking about the domestic Elysium, and you’ve got those weightless young kids jumping over a vaulting horse, doing somersaults, as you’re talking about massacres and disasters. So suddenly those are both, bodies that are a young child’s ‘everything is possible’ jump, and also bodies that are flung through the air from an explosion, from being shot. And because you don’t state that this is the analogy, it leaps out at you, while watching it, as a possibility. And in that sense, I think it pushes us to our most alive state of allowing ourselves to understand we exist by making these connections. It’s so fundamental in these films, I think it is what gives them their profundity. So it’s both about those subjects and about how we make sense of the world. You see a donkey and there’s a child riding, most probably on the beach, but because the context isn’t given and it’s floating there, you’re able to push that into other images. Is this Christ riding into Jerusalem on the back of a donkey? What are all the associations of donkeys that come into your head and are provoked by it?

And those are my notes.

Oh, but my seventh point is what I can understand from all of the above, from you as a filmmaker, for myself as a filmmaker. What I actually understand as a filmmaker. Like, these are also notes to myself to remember when making my next film. About close-up sound and distance. They’re things that we have in common. It’s the difference between a text that you’re reading and a text that you’re hearing. A song with one word, then you read something else. The idea of understanding history as a collage rather than a single narrative.

The films are such a remarkable body of work. I’d seen almost all of them, all the ones that were on your film survey at Zeitz MOCAA [Museum of Contemporary Art Africa], where I went from room to room. But this is somehow a different kind of viewing, just quietly here by myself in the studio.

You’ve said somewhere that home movies, because they are mostly from the 1950s and ’60s, and because of their form, feel distant—compared to, say, the high-definition digital film today, which would equal realist form. You’ve suggested how the form we now read as real is the technology that we see through, in effect: it shapes how we see ourselves. You’ve said how your mum would send the reels to Joburg and when they came back she would put them through the projector, put up an old sheet as a screen, and you’d start looking at yourselves, your lives.

In our house there was a certain panic around home movies; you knew you had three minutes, it was going to last three minutes, the 8mm, and my father was a terrible, terrible cameraman. So everything would be there for a quarter of a second. One of the pleasures of looking at your films is the thought that you found footage where people actually looked at something, where you could see something. Rather than in the half-second shots of my childhood watching, of people standing still, waving, not knowing what to do. And so there is something in this, whereas now, as you say, on your phone you can shoot 4K, and you can shoot an hour of it, not three minutes. It’s difficult to know how you would create the effect of those home movies now: you’d have to put on a stupid filter to make it look like an 8mm film. A kind of fakeness would be built in. But as you say, the scratches, the imperfections, the aging, the emotion of the film, are crucial. I mean, it’s interesting because you have an aged film and now it gets held in time because of the digital medium. If one could preserve the digital medium, would it keep that period of aging in the celluloid that was there when you projected it, I wonder?

Also, in those early home movies, you can’t rewind and relook as you film. In the animation that I do—which, until the last film, was shot on celluloid, either 16mm or 35mm—it’s the same thing. You have to think ahead; you can’t think backwards. In other words, you can’t see what you’ve done and go back and look at it. You have to remember or anticipate what it was and think forward. So, you’re doing a piece of animation, and then, OK, the next frame must be there and there. And in the digital world, there are so many ways of seeing the last frame, what you did in the last four frames, and going back and seeing what I should do next. And so I made it a rule for myself doing animation not to use any of those programs but to just keep going on the memory stick or on the recording card, to keep going forward. Otherwise, you keep looking over your shoulder.

I guess that was my eighth observation as I relooked at your films this afternoon.

Oh, one more thing. In one of our conversations you described how you try out sound just as you try out images when you’re making a film. You said this was like ‘auditioning’ bits of footage and sound, trying them out until something suddenly clicks. That’s how you described it. It’s astonishing how that click works in your films. Sometimes it’s about rhythm, which enables the film to keep moving; sometimes it’s about grammar, which tells us this causes that, all this comes before; also, there isn’t a clear narrative that tells you where the verb is and where the subject is, and where the full stop is and how to go on. Like in My Lovely Day, there’s never a full sentence: not ‘but it was dead’ or ‘it was dead’ but ‘was dead,’ ‘went there.’ The writing has such strength. The New Parthenon is a fantastic potted history of Greece and South Africa. People who died on the island were the first victims of the Cold War—just in one sentence: ‘Greece thought she’d go east / but Russia chose Romania.’

It’s astonishing how different pieces of sound make you see things differently. Miriam Makeba following Frédéric Chopin in The Master Is Drowning—you can’t believe the speed is the same, and then you hear differently and you think, oh, the film has slowed, but in fact it’s exactly the same; or you think, this is too fast to watch, but it’s the exact same piece of film. That was note nine.

We could end by coming back to my earlier idea that in a sense the films will always be you. The thing I didn’t talk about, which I loved, I loved, is the water. In My Lovely Day, while you’re talking about holy water we’re seeing synchronized swimming, which becomes this vortex of water made holy. And then, of course, the synchronized swimming is another form of the Greek dance, that circle slowly going around. In that one image you’ve kind of sanctified the swimming pool. So you’re saying this may be a domestic image, or a suburban image, but it has all these other echoes of what water is, with a soaring Greek chorus, there’s a kind of compressed richness that comes from how things fit together. And in The New Parthenon, that gorgeous shot of a naked woman getting into the Aegean—but you tell me it’s Lake Malawi. I completely believe she’s in the Aegean, completely.

Has anybody written about ‘the liquid world of Penny Siopis’? I mean, so many of the films have water in them, swimming, the octopus, the cuttlefish diving into the water …

In the end—OK, this is definitely my final thought—I think with your work and with mine, one has to feel that the work has a resonance for you and for people that you’re working with immediately around you, in the hope that if it’s working for you, other people, in wider areas, in different contexts, will understand it. You don’t have to have grown up in South Africa or in Greece to be able to understand. I suppose for me it’s easy because I grew up in the same era of those home movies. But my guess is that we are very good at understanding context. And if we’re not good at understanding them correctly, we’re good at making a creative misunderstanding of them. And even people who don’t know 16mm home movies, and don’t know particularly the political history of Greeks under the colonels or who Verwoerd was, still will find a connection. That’s the belief—that they’ll still find it, that when you showed it in France, it still spoke to the people in France, and if you showed it in Romania, it would speak to people in Romania.

In all of this, you discover that people’s abilities to map their own experiences onto the clues that you give them are very strong, particularly in a way because the clues are open-ended. I mean, I was astonished when we did Ubu [and the Truth Commission] and there was, you remember, the story of the parcel bomb that was sent disguised as headphones or a Walkman. And at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission they showed an image of a pig’s head that they tested it on, which had blown the pig’s head up, blown his ears off. And so in the play, one of the projections to talk about violence was an image of a pig’s head with ears, and headphones were put on and ears are exploded and people said, ‘Oh, but for people who don’t know what it is, it’s going to be rubbish. What sense will that make to anyone in Germany or in the Czech Republic? They don’t know that specific story.’ And yet the response we got when we asked people whom we questioned about this was that, no, they didn’t know that story, but it didn’t really matter because it was (a) an image of shocking violence; and (b) so strange and specific, they thought it must be true. In the sense of how would one invent that if it didn’t come from somewhere?

~~~

Publisher information

Penny Siopis is internationally acclaimed for her pathbreaking paintings and installations. Your History with Me is a comprehensive study of her short films, which have put her at the front ranks of contemporary artist–filmmakers.

Siopis uses found footage to create short video essays that function as densely encrypted accounts of historical time and memory that touch on the cryptic and visceral elements of gender and power. The critics, scholars, curators, artists and filmmakers in this volume examine her films in relation to subjects ranging from the history of Greeks in South Africa, trauma and cultural memory, and her relationship with the French New Wave to her feminist-inflected articulations of form and content and how her films comment on apartheid.

They also highlight her Global South perspective to articulate a mode of filmmaking highly responsive to histories of violence, displacement and migration as well as pleasure, joy and renewal. The essays, which are paired with vivid stills from Siopis’s films throughout, collectively widen the understanding of Siopis’s oeuvre. Opening new vocabularies of thought for engaging with her films, this volume outlines how her work remakes the possibilities of film as a mode of experimentation and intervention.

Contributors: John Akomfrah, Sinazo Chiya, Mark Gevisser, Pumla Dineo Gqola, Katerina Gregos, Brenda Hollweg, William Kentridge, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall, Griselda Pollock, Laura Rascaroli, Zineb Sedira, Penny Siopis, Hedley Twidle, Zoé Whitley

‘Nobody but Sarah Nuttall could have put together such a stellar collection to make the unanswerable case for filmmaker Penny Siopis as an artist of unique aesthetic and social significance. Forged in the political fires of South Africa, Siopis’s ravishing, demanding films resonate across the global landscape. This will be a must-read anthology for anyone interested in how artistic practice can help create a path away from cruelty toward a world of freedom and justice.’—Jacqueline Rose, author of The Plague: Living Death in Our Times