What does it mean to want grace after such a thing as apartheid? What might it look like? God’s Waiting Room is willing to plunge into the corporeal, embodied messiness of these questions, writes Wamuwi Mbao.

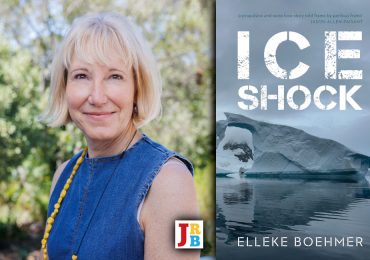

God’s Waiting Room: Racial Reckoning at Life’s End

Casey Golomski

Wits University Press, 2024

Most white South Africans enthusiastically supported apartheid. Most of them—Afrikaans and English alike—benefited from the state’s coarse racial fictions, its grandiose pseudo-scientific claims and its social dishonesties. A disquieting number of white South Africans were happy to continue living in bogus ignorance of how their white supremacist la-la-land was being sustained. Many of these happy white South Africans were shocked and dismayed when the apartheid state was wound up and liquidated.

In a tediously truth-divergent present, dominated by the global resurgence of various brands of squalling right-wing agitation, it should come as no surprise that a bellicose strain of apartheid denialism has found cosy bedfellows with the Nazi-Zionist-Fascist trifecta of awfulness. Apartheid nostalgists are pastiche right-wingers. They mimic the mannerisms of their goose-stepping northern hemisphere cousins, but what they really want is simply to be returned to apartheid’s organising logic: the affordances it granted them, and the freedom to enjoy those affordances without being made to feel bad about it.

Apartheid’s dirigisme was a financial catastrophe. The cost of the vapidly boastful folly that was propagandised as the highest standard of living enjoyed anywhere in the world —measured in skin cancer, artery-clogging levels of red meat consumption and the ability to beat workers without censure—would only truly be known after it was annulled. The amenities that were provided to white people almost exclusively are now crumbling under the weight of a population that includes the dispossessed, excluded and criminalised black people who built them. The social infrastructures that undergird these amenities—healthcare, socioeconomic assistance and other forms of citizen-directed welfare—are all inscribed with the long history of racialised corruption that defined South Africa’s state development in the first half of the twentieth century. In the town where I live, the posh homes for the elderly, all of which have dubiously optimistic names taken from some Shady Pines book of clichés, such as La Clemence (‘Embrace Your Retirement’) and Langverwag (which translates as ‘long awaited’), have lengthy waiting lists. Most of these facilities, to judge from the publicity materials and the old folks who periodically emerge to take some sun, are populated exclusively by white people who are (let’s join the circuit) old enough to have lived through, participated in and benefited from apartheid.

So runs the subject matter of God’s Waiting Room: Racial Reckoning at Life’s End, a profoundly beautiful exploration of what decline and dilapidation mean for those whose lives were largely lived in compact with racial separation. Casey Golomski’s book calls to mind the similarly insightful work of writer-theorists such as Hugo ka Canham and Christina Sharpe. It engages a broader readership than its university press packaging would suggest, with the local edition featuring a muted cover and sombre subtitle. If the architecture of the book suggests a weighty academic study, what unfolds is a compellingly inventive ethnography that is attuned to the power of the connotative. It draws you in by asking you to consider an interesting social problem: how the old-age home combines the socially diminished (old people, mainly white) and the socially precarious (those who look after them, often poor, working-class, and black) in a relationship of managed frictions and custodial endurance.

The book records Golomski’s experience of Grace, an old-age home in Mpumalanga, and distills his observations into several interlaced chapters that form a story about the thresholds of diminishment: where does ageing, with its dehumanising abasements and its infantilising, encroaching dependencies, intersect with the reductive humiliations and vulnerabilities of racism? The old-age home is ‘a liminal zone, an unusual place betwixt and between worlds, where you make new or unexpected relationships with the folks you find in there with you’. We follow Golomski into the genteel, manicured grounds of a facility that, we might observe with some resonance, has been built on the graves of the dispossessed and the moved-on. There, at an intimate distance, we peer over the author’s shoulder as he follows the care staff around, observing them as they go about their duties. We follow as he comes to know the shifting cast of late-life residents who, in their own ways, are reckoning with what it means to be dying out, thirty years after democracy. These ‘old white people’ are often dismissed by society as the hangover of something that has been put out to pasture. But, as Golomski reminds us, it is both ageist and exculpatory to assume that older people are incapable of complex or changing ideas about the world and those with whom they share it. Over the course of the book, the author’s patient, difficult conversations lattice into something that speaks with great acuity to and with the social.

Creatively spun though God’s Waiting Room might be, it is framed by a comparison of depressing facticities: South Africa’s belated National Health Insurance plans on the one hand, and the United States’ much-maligned Obamacare reform law on the other. Both countries faced much skepticism: plans to get the NHI off the ground in South Africa have been bogged down by the special pleadings of the private health insurance industry, whose members (predominantly the middle-class) cling to it even as it proves debilitatingly expensive. In the US, Obamacare was kneecapped by the Republican opposition, whose efforts to frame it as an attack on American freedom successfully undermined what would have benefited those who would later elect a white supremacist to the highest office in the land:

In both places, attempts to build better systems and spaces to care for people—including elder care, something we may all inevitably need in some form as part of being human—were stymied by white anxieties […] In a way, in South Africa and the United States, two countries historically shaped by white supremacy, changing the system for older people in particular, or all people in general, would erase the privileged differences that long defined a part of who they were—it would somehow make white people feel ‘less than’. In a way, it would make them feel black.

Golomski’s book lingers amiably amid the ludic grossness of failing old bodies: seeping wounds, bowel actions, dementia. As he points out, ‘frail older adults reveal the truth that we are forever changing in interwoven physical, psychological and spiritual dimensions, concentrated in the form of a de-muscling, thinning or swelling body of bones, blood and skin […] and that we may carry with us aspects of ourselves and past actions that we can’t fully dispossess if we wanted to’. The book invites the reader into an act of witnessing that can feel uncomfortably close, even unsettling. And, as old people do, the inhabitants of Grace often express loathsome sentiments. Golomski does not sensationalise this or make excuses for their failings or their moral turpitude. Instead, he places the appalling intriguingly and with deft narrative ability within the broader context of white people’s undue sense of entitlement to ‘grace’—a word that becomes a poignant motif. What does it mean to want grace after such a thing as apartheid? What might it look like?

God’s Waiting Room is willing to plunge into the corporeal, embodied messiness of these questions, and it does so in a well-conceived manner. This is a mindful book, which roams productively through an under-explored area of our national psyche, inviting us to speculate on what a more enriching ‘otherwise’ might look like. And it is magnetic in the way it scripts the conditions of an unlikely and provisional grace.

- Editorial Advisory Panel member Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on X.