The JRB presents—exclusively and for the first time in English—a new short story by Niq Mhlongo.

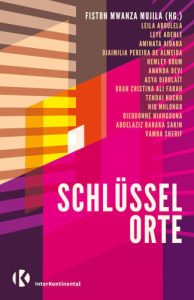

This story was first published in German, as ‘Hundeleben’, in the short story collection Schlüsselorte (2023), edited by Fiston Mwanza Mujila.

Schlüsselorte

Edited by Fiston Mwanza Mujila

InterKontinental, 2023

~~~

Dog’s Life

Mauerpark, Berlin. It’s the last week of August, a hot Sunday. The sky is radiant and blue and there’s no wind. The flea market is crowded. People are walking about in pairs, in groups, with dogs or alone. There is an air of cheerfulness everywhere. It makes the park comfortable. My girlfriend, Ursula, is busy taking pictures with her camera. That’s what she does for a living. I’m following her, holding our dog Ginger’s leash. There, at the open air atrium, karaoke singing is going on. I can see a large crowd surrounding the dueting performers. People move their heads from side to side along with the tune, enjoying the music and the singing. Further away, by two tall trees, a group is doing aerobics. Jerusalema by Master KG is blasting on the boombox. Ursula stops to listen. I know she loves this song. She dances with her head. Her hair is tied back into a stout ponytail.

We come to this park almost every Sunday. It is within walking distance of our apartment in Prenzlauer Berg. We even buy second-hand clothes here. Sometimes we just come here to read our books. We love the atmosphere.

But today is different. A medium-height black man with a round face is standing next to the steel exhibition structure of the Berliner Mauer along Bernauer Street. He is wearing shabby, stained jeans and worn-out shoes. He is talking loudly and pointing randomly at the passersby. A cold, impersonal voice comes from his lips, which look a bit thick, as if swollen.

‘I’m more clever than your Angela Merkel,’ he shouts, pulling up the legs of his trousers and scratching his skin. ‘I’m not afraid of anything. I’m not scared of saying the truth as it is. Danger means nothing to me. It does not frighten me. It does not engage my head or my heart.’

Onlookers exchange bewildered looks. A woman next to me frowns, shakes her head and gives the man a where are you from stare. She is walking with a kid carrying an ice cream that looks like the Olympic torch. Ursula smiles as she takes a picture of the man. Her eyes contain the excitement of the drama that is occurring, transfixed on the man’s forehead.

‘I’m more intelligent than your Otto von Bismarck, your Helmut Kohl and Joseph Goebbels. I’m smarter than all of them and all of you.’

His face looks hardened by pain and experience. He looks old and abandoned, as if sucking hopelessly at the bitter, butt-end of Berlin city life. I can spot perspiration on his brow as the heat dances on his forehead. It shimmers like a sheet of badly-formed glass.

He unbuttons his shirt, to slip it off, as if to display his great torso, decorated with a gallery of tattoos. ‘Look at me, the university of intelligence. You can’t compare me to your Angela Merkel. I’m super intelligent. You people need to unburden yourself to feel free like me.

I stand there, trying to understand what the man is saying. Ursula continues to capture the moment with her camera. The man notices her and makes a gobbling sound of laughter in his throat. ‘You can take as many pictures as you want and display them in your bedroom. Come on, don’t be shy, young lady.’

He has a smile that spreads over the whole expanse of his face in a way I have never seen before. His mouth opens from ear to ear, showing red gums like a sliced watermelon. A few people stop and eye him, then each other, silently. One elderly woman spits with indignation. Besides me, Ursula giggles and then looks at me.

‘Do you understand anything he is saying?’

I shake my head. ‘Not all of it. But the man looks frank and honest.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I mean one can’t just imagine shit like that out of the blue. There must be some truth in it.’

We both laugh. A group of people have paused in their game of cards to look at the man with curiosity. One of them breaks into a chuckle as she watches him talk. The man keeps his face stern, assuming an air of authority against grins and exchanges of looks.

‘Yes, all you Germans can’t tell me anything. I’m smarter than you all. I’m smarter than you, you, you and you,’ he points randomly at the crowd in front of him, but stops as he spots me.

The spectators gasp and bodies grow stiff with tension. I’m embarrassed, but amused at the same time. To me, his words sound like a breach of the peace in the park. But as he stares at me, I suddenly feel a pang of something akin to guilt in my chest. I try to avoid his eyes, pretending to look at the blue-grey pigeons as they sail from the roof of one of the kiosks. They drop to the ground and strut with smooth-feathered importance among the fallen scraps of food near the card players, their sharp beaks pecking skilfully past their pointing breasts. There is silence around the man, as if people are assessing his menace.

I look around. I’m the only black person in the sea of white people. The man nods at me and then smiles. His eyes spark. I know this nod. I have seen it many times among us black people in European cities. It comes automatically when we spot each other in the street. It’s a form of acknowledgement among us, the migrant bodies of Europe. It is a nod that often comes with a smile that seems to say, Whatsup my African brother. You are not alone. I don’t know you, and how you came here. But I’m glad you also made it to this cold, hostile place. Give me a shout if you need anything.

Ursula takes a shot of the man smiling with her camera. He laughs hoarsely, then scans the faces turned in his direction—curious, expectant, gloomy, apathetic, hostile faces. A mixture of awe and curiosity.

‘Yes, I know you don’t believe me, but I’m smarter than your Angela Merkel,’ the man says again. ‘I believe in non-violence, I believe in goodness, love and justice.’

A few people are now passing the man on either side, wondering what is wrong with him, but I feel like my whole being is struggling to grasp what is happening. In my judgemental mind I’m thinking he is just an immigrant like me, in a strange city, ignorant of the habits and customs of his hosts. I mean, people here in Berlin are strange to me too. Dog owners only greet dog owners to talk about the breed and age of their dogs. Joggers only greet joggers to compare notes on their fitness and the calories they have shed. Hikers only greet hikers to discuss best hiking routes. Otherwise no one greets in this city. They just stare at you. Above all, you don’t greet everyone you meet with a handshake. It is a complicated city. Trying to understand Berlin is like trying to make sense of why Monday to Friday is five days while Friday to Monday is just three days.

‘Come on, it’s time to go,’ Ursula says.

‘Let’s wait a bit.’

‘You are stealing God’s sweet time by listening to this man. He has been saying the same thing ever since I knew him.’

‘You know him?’

‘Of course. Everyone here in the park knows him.’

‘Is that so? For how long have you known him?’

‘I don’t know. Maybe about four years?’

‘Wow, that’s a long time. He seems to be in the wrong life.’

A silence between us lasts for a few seconds. In front of us pigeons rise on fluttering wings to settle on top of a tree. Ginger tries to free herself from the leash to chase them. Ursula speaks to her to calm her down. She jumps at her, wagging her tail and making little barks of complaint.

‘But we have been coming here for the past three weeks. I have not seen this man.’

‘Maybe it’s because it was rainy. Everyone in this city hibernates during rain and cold.’

‘Or maybe he was preaching somewhere?’

‘Well, if you call that preaching. I’ve seen him making his crazy soundbite speeches at the Tempelhofer and Treptower before.’

‘I like him. He has a very vivid imagination and I think the world could never recreate a bold example of mankind like him.’

‘I only wish I had his boldness, that’s all.’

‘Please take a photo of me with him.’

‘I already have. If you like, I also have a short video of him that I took about a year ago.’

‘I’m glad you also admire him,’ I grin.

The Prenzlauer Berg roofs are tinged with the orange glow of the dying sun when we leave the park and walk home. The heat of the atmosphere is soaked with the noise of the trams, cars and the busy crowd on the streets. The sun is dwindling, leaving the lavender twilight to filter over the block of apartments in front of us.

‘Do you think that man in the park has a family around?’ I ask.

‘I don’t know. Maybe. But it seems to me his people don’t care enough to trouble themselves to look for him. Or they are just glad not to have the embarrassment of his presence any longer.’

At home, after dinner, Ursula and I are busy checking the photos. I find a fascinating picture of the man at the park staring directly at me and smiling. I post it on my Instagram and Facebook accounts. Minute by minute, the likes roll in from back home in South Africa.

***

In the morning, I see a message on Facebook, a long text accompanied by an old picture of two boys aged between ten and twelve:

Dear Lungelo. My name is Lindani Gama from Joburg. I just wanted you to know that you have just solved a 43-year-old historical and political puzzle with your post last night. That man in the picture with you is my cousin, Senzo Nake. To cut a long story short, Senzo and I were close. We even joined politics together, and he was called Scorpion in the Black Consciousness Movement. My mother and his mother were sisters. We were born in 1958 in Soweto, Orlando East. We lost contact after June 1979, when we both went into exile via Lobatse, Botswana. I really thought that he was no more when he never came back home in the nineties. In that picture I sent you he is the guy on the left, I’m the one on the right. We have been trying to find out his whereabouts. The last time I heard of him he was somewhere in Yugoslavia, Belgrade. Some comrades had seen him in Sweden, others in Liberia and Ivory Coast. Scorpion’s mother, aunt Dorah, is in her nineties now with a memory loss condition. That is an advanced age. She will be very happy to see her son before anything happens to her. At least that’s her wish, which she has been telling me for years. It would be the greatest favour on your side if you would agree to assist me, if I come to Berlin to convince Scorpion to come home with me. All the expenses will be on me. Thanks again.

I allow myself to be carried away on a wave of empathy and optimism with these words, and I immediately consult Ursula about the possibility of helping Mr Gama’s family. At least the Mauerpark man now has a name, Senzo Nake, aka Scorpion. I’m somehow glad that he is a South African, like me.

‘Do you know this Lindani Gama?’ Ursula asks.

‘No. We have not met before. But I checked his profile. He seems to be a legit businessman. He runs a successful coal supplying company.’

She inhales deeply, as if to compose herself. Our glances lock, and she stares at me questioningly, as though trying to penetrate my mind. My thoughts keep curling round her question, which I didn’t answer properly.

‘What do you think?’ she asks.

‘Well, I think my help is needed here. I want to do it for the old woman.’

‘You don’t think this is some kind of a scam?’

‘No. Anyway, the man will be paying for everything. If I suspect anything wrong along the way I can still pull out.’

‘Be careful, okay?’ she smiles, and I can tell she approves of my foolish kindness.

Deep in some remote recess of my mind, I know Ursula is right about the possibility of me playing into the hands of a scammer. But I write back to Mr Gama and tell him I’m willing to help anyway. After a few more exchanges, he tells me he will be coming to Berlin in less than a month.

In a fever of excitement and anxiety, I count the days. In the meantime, Mr Gama and I have a few phone conversations.

‘Just to put you in the picture, I have contacted our embassy in Berlin to brief them on everything about my cousin Scorpion. They will help with the repatriation processes.’ ‘Repatriation process?’

‘Yes. The Department of Arts and Culture helps our former freedom fighters across the globe to be brought home. They have done that with a number of comrades. My cousin Scorpion also qualifies. They will even give him free housing and a monthly stipend.’

‘I see. So what is the next step?’

‘Of course it will be a long process. Firstly I will have to come to Berlin to make a positive identification of Scorpion. It has been years since we last saw each other. I keep playing that video you sent me. But it’s not enough to make any firm conclusions. We will have to do a DNA test. Luckily my aunt is still alive. Then the repatriation process will start.’

‘What do you want me to do?’

‘I would be happy if you could take me to where you last saw him. Maybe he will still be there. I would have loved to come with my aunt, but unfortunately she is too old and sickly to fly. The embassy will assist where they can once I have located him.’

‘Okay, I see. I will hear from you then.’

After the call I feel as if Ursula and I are heroes. Anxiety and anticipation are wreaking havoc with my mind and emotions. I’m elated to learn that we will both be playing a role in the reunification of a family. I mean, they were separated before we were even born, according to the dates. Plus, this is an opportunity to get introduced to our embassy. I have been in Berlin for about two years now and I don’t even know the address of our embassy. From what I had heard, embassies are unnecessary government expenses. Until now I didn’t know or see their purpose. Most South Africans see ambassadors as failed or unwanted politicians, discarded in foreign capitals so that they don’t make too much noise in the day-to-day running of the country. But today the role of the embassy is clarified for me. Maybe they can even sponsor our theatre projects as a thank-you gesture, I think.

***

Mr Gama calls me a couple of days before leaving for Berlin to tell me he will be staying at the H4 Hotel, Karl-Liebknecht Street, Alexanderplatz.

‘Is that close enough to you? Or do you want me to book for you at the same hotel to make things easier?’

‘No, that won’t be necessary. I live close enough.’

‘Do we need to hire a car? You think we can drive where Scorpion is?’

‘No need at all. We will use trams or trains, or even walk there.’

‘Thanks again. This means a lot to me and my family.’

‘I can only guess.’

I can feel a strange, inexplicable excitement coming from him. I know I’m not dealing with a scammer.

***

On the Friday Mr Gama arrives in Berlin, he invites Ursula and I to dinner at his hotel. He has a flabby body and a liquor-bloated, sagging face, like a half-filled balloon. He is in a mood of raucous good humour. I’m facing him at the table and he is drinking whisky. He has come with a few more photographs. When he speaks, he reveals his incisors, which protrude slightly. Ursula and I listen, watching his face.

‘I’m sure you have seen this picture before. It was 16 June 1976. That’s us here, Scorpion and I. We were in standard eight at Orlando High.’

Ursula and I take a closer look. Mr Gama takes a small sip from his whisky glass as if unaccustomed to alcohol.

‘Everything started with a police dog,’ he says as he puts the glass on the table. ‘It was a German Shepherd. I remember it very well. The police set the dogs on us. We were young and determined. We pelted the dogs with stones. Few stones hit one German Shepherd and it screamed with pain. That’s when all hell broke loose. The police became very angry and started shooting at us.’

‘What a story!’ Ursula says, holding the picture.

‘I know it sounds exaggerated, but it is the truth. That’s why even today I’m afraid of dogs, especially the German Shepherd. When I used to live here, the sight of dogs everywhere always gave me nightmares. Some people didn’t understand where my cynophobia came from.’

I make an effort to look fascinated by his story out of pure politeness. Ursula listens without making a face, not even nodding or shaking her head to indicate agreement or otherwise. I’m glad we left Ginger at home.

‘So, you were in exile here in Berlin?’ I ask.

‘Only for less than a year of training. I was in East Berlin, and then sent to Algeria and Zambia. I haven’t been here since the wall came down.’

‘That’s interesting to know.’

‘Yes, our solidarity with the GDR dates from our exile days. This is where I met a few comrades from Angola and Mozambique in the early eighties.’

‘How did you lose contact with Scorpion for so long?’ Ursula asks.

‘Well, while I was in Lobatse in Botswana in 1979, the ANC leadership tried to recruit us. We were fiery then and they wanted us to fight under their party instead of our Black Consciousness Movement. I agreed to join them, but Scorpion said no. The ANC took me for training here. I left Scorpion in Botswana. He was angry at me. He felt I had betrayed Steve Biko and the movement. We never spoke again.’

‘That’s sad to hear.’

‘I tried to get hold of him. I heard he was in Belgrade, and then Monrovia. At some point he was rumoured to be dead. I had thought this until I saw your post.’

A ghost smile lightens on his face, before he covers his mouth with his hand and wipes his forehead and eyes. He speaks as if he is always conscious of the sound of what he said before.

‘How is Scorpion’s mother?’ Ursula asks. ‘It must be very hard for her.’

‘Of course a mother’s love is a law of nature. My aunt is okay, but not well. She keeps asking me about him.’

‘So he never wrote to her?’

‘Writing letters was the most dangerous thing to do. The security police killed a lot of freedom fighters with letter bombs.’

‘That makes sense.’

‘Yes. My aunt last received a letter from Scorpion in 1981. He never said where he was, but he told her he was fine. That was the last she heard of him. She still has that letter today. But her memory of him was when we left the country in 1979. After Biko was murdered in 1977, the apartheid government tried to arrest every Black Consciousness member. Scorpion and I were known BC activists at Orlando High. We were constantly harassed by the security services. We knew we were targets, and so we fled the country.’

We say goodnight to our host with mixed feelings. Ursula tells him that after midday is the best time to meet the next day.

‘Berliners are late risers. They only wake up in the afternoon, especially at the weekend.’ I nod in agreement, as I have experienced the empty streets in the morning when I walk Ginger. ‘We’ll see you at one in the afternoon.’

As we make our way home, Ursula tells me she is not happy about Mr Gama’s hatred of dogs. ‘I am not convinced by his reasoning,’ she says. ‘Although I do feel pity after hearing his story of exile.’

***

It is not hard to locate Scorpion the following day. He is at his usual place, the Mauerpark, sitting on a concrete slab with another man. It is Ursula who spots him first. The man next to him has a thin, sharp face that is splotched with red. My heart races in happy anticipation as we approach. Scorpion is rolling a long cigarette. He seems entirely oblivious to us. With patient skill he carefully tears his Rizla into a rectangle. Lying between him and his friend is a well-fed black sausage dog. Ginger gives it a sniff, and Ursula and Scorpion’s friend start making smalltalk about the dogs in German. After a while they switch to English, to accommodate us.

‘I speak only French to women, German to my dog Bowie, Spanish to God and my friend Julio here,’ the man says. He has a hoarse voice with what sound like damaged vocal cords. ‘And then in English I speak the truth.’

‘But I’m a woman too, and you are speaking to me in English and German,’ Ursula says.

‘That’s right. I only speak French to single women,’ he says, and laughs at his own joke. ‘I mean, there’s always fish to be caught in Berlin if you speak French.’

‘Okay, I think you must give that tip to the guys. Not me.’

The man is dressed in tattered jacket, patched trousers and disintegrating shoes. He is narrow-chested and forever coughing, as if he has TB. His thick black eyebrows meet above his nose. It is the first time I’ve met a German with such a sense of humour. After two years in this city, I had come to the conclusion that Germany is not a nation of small talkers, unlike South Africans. They are serious people, always working on big projects, with no time to waste.

Mr Gama casts sidelong looks at Scorpion and says nothing. Scorpion is shaking the tobacco evenly along the trench of his Rizla. He has not looked up. He arranges his tobacco smoothly with the tip of his finger. His nails are thick. Some of them are the deep yellow of soaked lentils. Others have brittle white layers and look ragged from dryness. When he is satisfied with his arrangement, he rolls the paper deftly into a tube, licks one edge and pastes it down, before licking the whole paper to make it stick. In all this time he makes no effort to raise his head and look at us. Next to me, Mr Gama looks agitated. Finally he speaks: ‘Senzo, Scorpion. It’s me, your cousin, Lindani Gama? Remember me? It has been a long time. I have been looking for you all these years.’

Scorpion looks up quickly and it is as if he has seen a ghost. I see his hand shake violently. His eyelids take on an inflamed look, the sort you cannot forget. The cigarette he has taken so much time to roll falls out of his fingers. Then he takes a deep breath and frowns. He turns to Ursula and me, as if we are people he has once known and now has to struggle to remember. Angrily, he points at Mr Gama with his trembling finger.

‘The only Lindani I know is a traitor. I will never talk to traitors in my life. Go away!’

‘Please, let bygones be bygones,’ Mr Gama says. ‘Now we are old men we must do the right thing and give life a chance without holding on to the past. Aunt Dorah needs you. We all need you back home. It has been a long time.’

‘I will bury the past on my terms. I cannot be dictated to by traitors,’ Scorpion says, with a look of disgust. ‘Where were you when I was imprisoned in Italy for ten years—and in Spain for eight years for those stupid immigration charges? Where was your ANC then? You left me wrapped in a thick fog of fear, sadness. Because of your greediness you left me vulnerable.’

‘I’m sorry about how you feel. I don’t want to dampen the atmosphere between us with the heaviness of the challenges at home, but your mother is sick. She is ninety-two. She is always talking about you. Your brother, my cousin Samora, passed away two years ago from Corona, and your sister Rosie died last year.’

At the mention of these names, Scorpion looks uneasy. Without a word, he picks up his cigarette, lights it and puffs quickly. Smoke trickles from his nostrils.

‘I cannot be bribed into returning to what you call home. Your performance will not force me. This is my home now. Coming here changed something in me. It awakened the possibility of what my life can become beyond the boundaries of apartheid, prison and your betrayal.’

‘I cannot go back without you. I promised that to Aunt Dorah. The least you can do is to visit.’

‘You cannot come here and tell me to go home when I have finally managed to scrub off the humiliating memory of your betrayal. Your Senzo Nake no longer exists. He was replaced by Julio Hernandes. I let go of Senzo in Lobatse, where you left me, and I have accepted that life goes on without you. I have found hope, restoration and rest here. Now I will politely ask you to leave.’

‘Please don’t do that to us. I know the mood in exile was always sombre and void of hope, but it was gloomy for all of us. Now the country is free. Let’s go home and enjoy the fruits of our freedom.’

‘You want me to leave my friends and family here to go and start from scratch because it will boost your selfish ego. Never. Only traitors like you will survive in that godforsaken country. I’m fine here. Now I really want you to leave me in peace.’

Their conversation is turning loud, and attracting attention. Scorpion looks around him, boring his eyes into each person in front of him. For an instant he hesitates, as if he has something he isn’t sure whether to tell us. Then he stands up and walks towards Bernauer Street.

‘If you keep following me I will call the police.’

Mr Gama looks desperate, humiliated and disappointed. As we leave for the U8 U-Bahn at Bernauer Street, doubt assails me. I’m stunned by the realisation that Scorpion has a life full of holes and secrets that he cannot share.

‘I’m sorry it didn’t go according to plan,’ I say. ‘This must be very hard to bear, probably the hardest thing.’

‘No need to be sorry,’ Mr Gama shrugs. ‘I’ve grown to value life’s unpredictability. It is also my fault. I was shortsighted when I left him alone in Botswana all those years ago. I’m hurt that he won’t permit me to be part of his life again. But I’m not giving up yet. Even if it means I have to stay here another week. I will find a way to convince him.’

‘I think letting his mood simmer for a few more days will be the best option,’ Ursula says.

***

Over the following few days, Mr Gama and I walk in the park every afternoon, in the hope of seeing Scorpion or his friend again. At first, we are unsuccessful. But then, two days before Mr Gama is due to leave Berlin, we come across Scorpion’s friend walking his sausage dog. At first he won’t talk to us, and he ignores us as he passes. But then he turns back to say something.

‘My friend has disappeared because of you.’

‘Disappeared to where?’ Mr Gama asks.

‘You tell me, because I don’t know. I have not seen him since last week when you made him angry.’

‘I was only trying to bring my cousin home.’

‘I have lost a great friend because of you. Now I don’t know where to start looking for him. I blame you for meddling in his past and his painful memories that he didn’t want to be touched.’

‘I’m sorry too. But I hope you understand the pain and all the emotion of losing a friend and a cousin for more than four decades.’

‘He is my friend too. He and I both come from far away. I’m originally from France, and I met him here at the park about seven years ago. You see, back then I had a neighbour who liked taking showers between nine and eleven at night. I asked her to shower earlier and she ignored me. The sound disturbed my peace. I decided to walk to the park every night to ease my mind.’ He coughs, and it sounds like the explosion of a faulty engine. ‘During one of those walks I met Julio. We became friends. When the person I shared my apartment with moved out, Julio moved in with me. He taught me my Spanish, which is now perfect.’

‘I understand. We have both lost a dear friend. Maybe we should help each other look for him.’

‘We will see.’

Before he catches his flight back to South Africa, I promise Mr Gama that I will let him know if I see Scorpion again.

‘At least I know he is still alive,’ he says.

~~~

Niq Mhlongo is the City Editor (on hiatus). He was born in Soweto, and has a BA from Wits University, majoring in African Literature and Political Studies. He has published five novels, Dog Eat Dog (winner of the the Mar de Letras prize), After Tears, Way Back Home, Paradise in Gaza and The City is Mine, and three short story collections, Affluenza, Soweto, Under the Apricot Tree (winner of the Herman Charles Bosman Prize) and For You, I’d Steal a Goat.