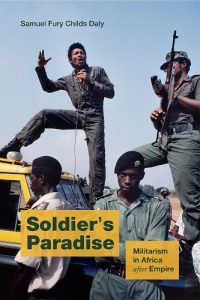

The JRB presents an excerpt from Samuel Fury Childs Daly’s new book, Soldier’s Paradise: Militarism in Africa After Empire.

Soldier′s Paradise: Militarism in Africa after Empire

Samuel Fury Childs Daly

Duke University Press, 2024

~~~

A group of men crowds around the news anchor’s desk looking ready for a fight. They wear full combat gear—camouflage, helmets, bulletproof vests. All of them are young and big, seemingly chosen for this task on the basis of size rather than seniority. Their drab uniforms contrast with the cheerful lighting of the tv station, which is better suited to weather reports than coup announcements. They pose like actors in an action movie, and they’ve cast themselves in the leading roles. These soldiers have taken over their government, and they’re not the first of their kind to do so.

After the end of colonialism, dozens of African countries experienced military coups. Across the continent, societies that had just won their independence from Europe became military dictatorships. Once soldiers were in charge, politics shifted course. Promises of liberty were replaced by a vision of discipline, and military principles like rank, readiness, and obedience supplanted the softer political values—equality, nondomination—that civilians had preached. Politics became a war of position between men in uniform, and in some countries that war raged for decades. Eventually most armies returned to the barracks, and for a while it seemed like Africa had left military rule in the twentieth century.

It has not. From 2020 to the time of writing, soldiers have brought an end to civilian government in Guinea, Mali, Sudan, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Gabon. The journalists and diplomats who didn’t see them coming have fumbled around for an explanation, usually landing on shortsighted theories involving Russian meddling or foreign mercenaries. But these coups didn’t come out of nowhere. The soldiers in the tv studios are building on a deep political tradition: For much of the late twentieth century, Africa’s most pervasive ideology was militarism.

From the 1960s to the 1990s, African politics revolved around soldiers’ blood feuds and power grabs. The men who staged them were intoxicated by their own strength, brimming with ambition and nervous energy. ‘It has proved infectious, this seizure of government by armed men, and so effortless,’ wrote the South African sociologist Ruth First in 1970. ‘Get the keys of the armoury; turn out the barracks; take the radio station, the post office and the airport; arrest the person of the president, and you arrest the state.’ On the surface, their coups were about corruption, or bad behavior by politicians, or low pay. But militarism was not always reactive or reactionary. Nearly all militaries wanted to transform their countries, even though they didn’t always spell out exactly what they wanted them to become. Coups also came with ideas, and militarism—the ideology of rule by soldiers—aimed to make a new kind of society.

[…]Militarism is the most neglected of the modern era’s isms, but we ignore it at our peril. Like communism or capitalism, wars were fought in its name and societies were made in its image. Nigeria was one of them. So were Brazil, Pakistan, Indonesia, and wide swaths of southern Europe, Latin America, and the South Pacific. A large share of the world’s population lived under the jackboot in the late twentieth century, and for this reason alone soldiers’ political philosophies are worth our attention. So too are their psychologies. ‘One function of authoritarianism is to lock an entire people in a single man’s mind,’ Patricia Lockwood writes. In this era, millions of people were locked in the ‘military mind,’ as Samuel P. Huntington called soldiers’ mentality—a mind that was cynical, nationalistic, and obsessed with discipline. In Africa, the conservative realism of the military mind met the liberatory spirit of the decolonizing mind, and some strange ideas were born.

Many military leaders wanted to remake their societies in their own image—as colossal armies, real or figurative. Some believed that making their countries into vast open-air barracks was what would make them truly free. This wasn’t a contradiction to them. Soldiers equated freedom with self-control, and they argued that true freedom came only from the mastery of one’s own instincts. They saw civilians as a chaotic rabble who needed to be brought to heel. They valued discipline as an end in itself, and they saw no reason why this principle, which structured their lives, might not serve as a philosophy for everyone. With the reckless confidence of young men, they believed they could bend Africa into a shape resembling themselves.

Officers had total faith in the military way of doing things. If a factory owner ran his business more like an army, he would produce more and waste less. If a woman selling produce on the roadside could be made to think like a warrior, then she would become free—no longer a slave to her own impulses, discipline would allow her to ‘self-actualize’ (officers swore by pop psychology). If everyone did this, they argued, Africa would become a well-ordered Arcadia. To be clear from the outset: they were wrong, and my description of their martial philosophy is not an endorsement of it. The idea that discipline is freedom, beloved of drill sergeants and self-help books for men, makes for a very illiberal kind of politics. The ‘freedom’ of rigorous discipline feels like no freedom at all.

Militarism’s true believers hoped to make military values public values. Rules would be followed, authority figures would command universal respect, and everyone would be ready when the battle came—which was the telos that all soldiers trained for and many of them longed for. They were vague about exactly what that battle would be, but that wasn’t the point. Militarism was a way of life, an ethos, and a design for living. Its champions called it a ‘revolution.’ It had a procreative logic. The army would pluck promising young men from the countryside and induct them into the ranks. Those men would marry wives who would be partners in the military revolution. Their children would be raised to be good soldiers or good wives to soldiers, and the cycle would continue until the revolution was complete. If the colonizers came knocking again, this time Africa would be ready for them. To militarists, building a strong army and building a strong society were one and the same. Making the state into a war machine was what would make it work.

Soldiers believed they were building a paradise, and that belief is critical to Africa’s modern history. But this was a soldier’s vision of paradise, which was not a place most civilians wanted to live. ‘Everyone looks to government to lead the country into the paradise that was promised during the period of agitation for Independence,’ wrote the Ghanaian coup-plotter General Albert Kwesi Ocran. But paradise meant more than one thing in independent Africa. To the poor, ‘the promised paradise is more and cheaper food to eat, cheap clothes, … shelter, soap, kerosene, drink.’ To the rich, ‘paradise means more high offices and better pay for themselves, improved living conditions, higher education (if possible free), improved roads, more industries, more imports of foreign goods.’ In public, military officers insisted they were creating a paradise for the downtrodden. Behind closed doors, they reassured the bourgeoisie that they were building a different kind of society—one designed for them, where contracts would be juicy and capital would flow freely. But what they ended up creating was a paradise for neither the rich nor the poor. They built a ramshackle utopia for themselves, at the expense of everyone else.

As one military regime gave way to another, the distance between soldiers and civilians grew. Officers began to see themselves as a caste apart, cut off from the public they ostensibly served. They were different from the ordinary people who milled around outside their parade grounds, ill-mannered and unwashed. Soldiers had their own rituals and values, their own lingo and dress. They lived together in barracks or on bases with their families, and they saw those bases as islands of order in seas of chaos. The military depended on civilians for less and less as time went on, and officers began to speak of ‘taming’ people, as if they were wild animals.

During militarism’s bloody denouement in the 1990s, Nigeria’s military would abandon its goal of transforming society. Under the dictatorship of General Sani Abacha, soldiers no longer spoke of military rule as a mission; it was an opportunity to loot the state, which they did brazenly. They still compared civilians to animals, only now the goal wasn’t to ‘tame’ them—it was to cage them. A Lagos businesswoman looked back on these final years of dictatorship with undiminished fury. The ‘jackboots’ who ran the country into the ground were ‘hot-blooded young lions with no respect for human life,’ Nkem Liliwhite-Nwosu wrote. ‘Blue-blooded aristocrats who spoke with authority through the nozzle of the gun; ignorant greenhorns who claimed to have the solution to problems which their refined, erudite, old fathers could not solve, and who ended up compounding the problems for us all.’ Many civilians shared her rage about what soldiers had done to their own countries.

~~~

- Samuel Fury Childs Daly is Associate Professor of History at the University of Chicago and author of A History of the Republic of Biafra: Law, Crime, and the Nigerian Civil War.

~~~

Publisher information

In Soldier’s Paradise, Samuel Fury Childs Daly tells the story of how Africa’s military dictators tried and failed to transform their societies into martial utopias.

Across the continent, independence was followed by a wave of military coups and revolutions. The soldiers who led them had a vision. In Nigeria and other former British colonies, officers governed like they fought battles—to them, politics was war by other means. Civilians were subjected to military-style discipline, which was indistinguishable from tyranny. Soldiers promised law and order, and they saw judges as allies in their mission to make society more like an army. But law was not the disciplinary tool soldiers thought it was.

Using legal records, archival documents, and memoirs, Daly shows how law both enabled militarism and worked against it. For Daly, the law is a place to see decolonization’s tensions and ironies—independence did not always mean liberty, and freedom had a militaristic streak. In a moment when militarism is again on the rise in Africa, Daly describes not just where it came from but why it lasted so long.

2 thoughts on “‘In Africa, the conservative realism of the military mind met the liberatory spirit of the decolonising mind’—Read an excerpt from Soldier’s Paradise by Samuel Fury Childs Daly”