Salimah Valiani chats to Anna Stroud about maps, trees and all the ingredients for love one can find in Johannesburg—and shares a brand new poem all the way from Canada.

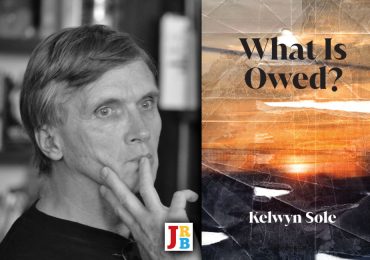

IGoli/EGoli

Salimah Valiani

Botsotso Publishing, 2024

Anna Stroud for The JRB: In your 2019 story-poem, Dear South Africa, you write:

like a small glass of genuine tequila

you are one of the best intense places I’ve

experienced

If South Africa is ‘like a small glass of genuine tequila’, what is Johannesburg?

Salimah Valiani: Jozi, as I like to call it—such an affectionate, familiar naming—is the unblossomed tiger lily bud and red canna caught in a line of sun, as I say in the opening poem of IGoli/EGoli:

‘On love (xxxiii)’

as with

tiger lilies

all buds

do not

blossom

but like a

red canna

caught

in a ray of

sun

the hope

of the memory

of the hope

that the bud

would blossom

is tall and

red

looming blood star

Tiger lilies are indigenous to East Asia, but cultivated in various parts of what used to be the British Empire, including Johannesburg. Its bulb has healing and medicinal qualities, as does Jozi, for the many diasporic peoples escaping to Africa’s largest world city. So even if the bud doesn’t flower, the tiger matters. Its being makes a difference. Canna, on the other hand, is a flower native to the Americas, from the Caribbean to the Andes to northern Chile. It is a tuber that can be eaten, and its long stalk and bright flower are just as grounding as the starch of its root. The canna is a flower I first noticed in 2006, when I was living in Canada’s capital city, Ottawa. The poem was actually written then, but I did not publish it until I put together this collection and realised the poem is so fitting to Jozi, apart from the connotation it had for me when I wrote it.

The JRB: Your new collection, IGoli/EGoli, published by Botsotso, is described as a ‘sociopolitical reading of Johannesburg’. What does that mean and what is the significance of the title?

Salimah Valiani: I am a poet with a doctorate in sociology, so my research tends to be constructed in original, out-of-the-box ways, and my poetry often involves research. With this poetry collection, I think I’ve done the most research for poetry ever in my almost fifty-year life as a poet. It’s a non-fiction poetry collection—with ninety-nine pages and seventy-seven footnotes! This is because I think there is history to the political and social fabric and ecology of the city that many of us living in iGoli do not know. We just go about our days in Jozi, surviving, partying, brooding, without necessarily stopping to step back and see. Poetry helps us do this in a light, experiential way that research and analysis rarely permit.

The JRB: Let’s talk about the cover. I love the juxtaposition between the Jozi cityscape on the front and the lush vegetation on the back. How and why was this design chosen?

Salimah Valiani: As much as possible I have walked in Johannesburg, and taken photos, as I have in all places where I have lived. I gave the pictures to Vivienne Preston from Advance Graphics, who designed the book. For the cover, all credit goes to Vivienne, who lifted this particular statue—a woman and child, versus the male images we always connect with Johannesburg—for the front cover, and used one of her own photos of trees indigenous to Jozi for the back. As an old hippie painter, Vivienne captured the essences of the book through the design, for which I am ever grateful. You will notice that two different fonts are used for the two sections of the book—also Vivienne’s creation. Botsotso had no problem with this unconventional choice, which I am not sure many other publishers would have accepted. Botsotso connected me with Vivienne, so all of this tells you of the intimate, spiritual process of producing this book, which makes it quite radical in a variety of ways.

The JRB: You dedicate IGoli/EGoli to ‘the visit to the Women’s Prison, Constitution Hill, Johannesburg, that put my life on a new plain’. Tell us more about this encounter.

Salimah Valiani: I spent my first golden moment of iGoli at the Women’s Prison, with my lover-to-be, Phumi Mtetwa. The Women’s Prison is a special part of this story and its beginnings. I have written about it for Brittle Paper in a story titled ‘The girl next door’. The story was published in Fourteen: An Anthology of Queer Art, Vol. 1: We are Flowers, a project by queer people in Nigeria who wanted to mark the first year of Goodluck Jonathan’s regressive, anti-queer legislation with something that was both celebratory and evoking resistance.

The JRB: I’m obsessed with the map of your poems at the front of the book, and the images introducing each section. Could you speak to the inclusion of visuals in the collection and the theme of mapping and remapping in your poetry?

Salimah Valiani: Thank you, Anna, for these brilliant questions and such a close reading of my collection! I thought of doing a map in the book because we rarely see maps anymore. When I first moved to Jozi in 2015, it took me a long time to find a full map of the city. Online apps aren’t quite the same thing! I thought it would be great to map the poems of IGoli/EGoli to help bring out the city as I live in it and see it. Two of my closest friends are map-makers. One of them, Peter McLaren, in Toronto, agreed to do it. I asked Peter if we could map not only the poems about Greater Johannesburg, but also those referring to the places with which Joburg is connected through its many migrants, who are integral to the city. But with GIS [geographic information system] technology, which is what Peter used—in collaboration with me over two Zoom sessions lasting some six hours—the mapping is to scale, so a map the size of a house would be needed to illustrate the world city that Johannesburg is and that IGoli/EGoli reaches for. We settled on Greater Johannesburg, using some poem titles, and some poem page numbers, to mark up the map at the start of the book. As for the other visuals, these were again skilfully selected by Vivienne when designing the book. Most of them are pics that I have taken over the years.

The JRB: You have more than twenty-one poems titled ‘On love’ in your collection. What is the ‘love’ you’re evoking through your work and why is it important?

Salimah Valiani: I began to consciously conceive of love poems in my second poetry collection, Letter Out: Letter In (Inanna Publications 2009), which was inspired by the year I lived in Cape Town. At the beginning of that book I included three epigraphs:

They can move mountains/But only love/Can set us free

—Toots and the Maytals

In my ear love murmurs

my soul has fainted

All colours melt in

Love’s transparent sky

I am only an empty cup.

—Maulana Rumi

umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu

—South African proverb, meaning ‘a person is a person through other people’.

I very much attribute my conscientisation around the larger love, and my use of poetry as a means to explore it, to my experiences of South Africa. Through my various poetry collections since, the love poems have persisted. And the experience of iGoli crystallised the message of the larger love. I realised in 2017 or so that I needed to bring together the various love poems of my four published collections, along with new love poems conceived in Johannesburg. That process created 29 leads to love (Inanna Publications 2021). The book was launched online during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, and was the 2022 winner of the International Book Award for Contemporary Poetry. The message of love is resonating in ‘a world built and crumbling from taking’, as I put it in On love (xxx), the opening poem of my audiobook, Love Pandemic (Daraja Press 2022).

The JRB: One of my favourite poems in IGoli/EGoli is ‘Greenhill Grocer or, On love (xIix)’:

tucked among

raw mangos

curry leaves

Durban methi

sugar bean pods

coconut cubes

kumquats

drumsticks

umbili

garlic shoots

green bananas

tofu

I see

glassy red

glistening wrap

impossible first crunch

just like forty years

four countries

ago

Those final lines, ‘just like forty years / four centuries / ago’, are so beautiful. You’ve been a world traveller since you were very young (and even before that, given your parents’ transcontinental heritage). Could you tell me more about the role of travel and food in your poetry?

Salimah Valiani: We have actually been a transcontinental family and community for centuries, given my particular mix of religion that has crossed borders, persecution-driven migration in various rounds, and colonialism and its legacy, which landed us, most recently, in the settler state of Canada in the nineteen-sixties. Journeying is in my blood, with my first trips being camping as an infant in western Canada, and going to my mum’s birthplace, Uganda, at the tender age of one and a half! Seeing and living in new places, tasting new fruits and vegetables, or even the same ones in different places, are all learnings for me about our interconnected world. They are also leads to love—the hospitality with which people greet you as a stranger, the art and care in meal preparation and invitations, the under-recognised acts of cultivating and sourcing fresh raw foods for city dwellers, like I tend to be, to cook.

The JRB: Speaking of transcontinental stories, I recently read Paperless by Buntu Siwisa and your poems ‘On love (xIii)’ and ‘Footsteps (iii)’, especially the lines, ‘how often you noted / the way African sons / become estranged never returning home’, remind me of themes in his novel—characters from Africa trying to navigate the world without papers and the separation of families across continents. Could you speak more about these themes?

Salimah Valiani: Buntu is a friend, and toward the end of my reading of Paperless, I said exactly this to Buntu—so I am very impressed with our synchronicity, Anna! We must tell Buntu. When one is outside of Africa, one is always shaken by the breadth of the African diaspora, and the ongoing struggles of Africans, even after leaving what is often the mayhem and super-exploitation of home. But I found the same thing in iGoli, and began writing this poem, mainly about men I have known over a span of some thirty years of traipsing through world cities. In writing the poem I realised I am part of this very same phenomenon, having left the place where I was born and raised thirty-six years ago.

The JRB: Tell me more about your poems, ‘Ontvangs B Helen Joseph Hospital’, ‘Mammogram Waiting Room Roodepoort’ and ‘Pholosong Emergency’. How does your academic work on health and care influence your poetry?

Salimah Valiani: Health and healthcare are central issues around the world today. I explore them wherever I can, trying to point out inequalities and injustices, as well as visions of something better for all. In these three poems I am juxtaposing public and private hospitals in various parts of Greater Johannesburg, to highlight the gaps I fear we take for granted. In my research article here, I provide action that people in South Africa, including the privileged, can take to radically undo the gaps in healthcare. These are solutions that I don’t get to in the poems, which are asking us, for a start, to simply look closely and feel.

The JRB: I have a family of spotted eagle-owls that sometimes visit me in Melville, punctuating my workday with their ‘hoo-hoooo’ and ‘hoo-hoo-hooooos’. So your poems set in and around Melville, Meldene, Westdene and the Melville Koppies bring me so much unhinged joy. I’m particularly fond of ‘big little forest’:

yellow white purple

floating off the koppie

sun pacifying dark fruits

golden herb patching red black yellow white

towering poisonous mushrooms stubby umbrellas cone hats

cheetah trunk sitting trunk leaf frill skirted

weaving branches

nutty fruit

owl rock tilting with wind

proliferating lightness

Talk to me about your experience of Johannesburg through its diverse plant life. You walk a lot, don’t you?

Salimah Valiani: As much as I feel safe doing, I walk in Johannesburg. Mostly the suburbs where I live and the surrounding areas. I began wondering why there are so many trees in the Savannah? Why iGoli is said to be the greenest city in the world? This pushed me to do my research and find out. As I put together the poetry collection, I realised the trees of the city provide a subtext for many things: the history of colonisation and settlement, the conquering, and the many meanings and purposes of the indigenous trees most of us know little about, but which were once widely known.

The JRB: You write in so many different languages and styles, adding depth of feeling of nuance to your poetry. Why is that?

Salimah Valiani: Along with the trees, I wanted to highlight the breadth of the languages of Johannesburg. Some official, but less recognised languages, others not official, uncelebrated, but present. When the Johannesburg urbanist Tanya Zack—whose important book about the inner city of Jozi and its people, Wake Up, This Is Joburg, is a must read!—read IGoli/EGoli, she put a word to my technique. She called it the de-centring of English. So while I am writing in English throughout the book, I am also bringing words from the range of languages spoken in iGoli, which simultaneously brings out EGoli, the many underlying connections of Jozi with other parts of Africa, and the world as a whole. If we were to all actually grapple with this multiplicity, the teachings that come from knowing words and idioms in a host of languages would bring us closer, bring answers we may be looking for, and make us all wealthier.

The JRB: In ‘Dorothy Masuka in Sophiatown 2018’, you crafted a poem based on excerpts from a conversation with the Zimbabwe-born jazz artist before she died in 2019. Tell us more about the construction of the poem—where other people listen to a talk, do you hear poetry?

Salimah Valiani: There are several poems in the book that appear in italics. These are poems that I heard, as you have sweetly phrased it, in conversations with people in Johannesburg. In the Dorothy Masuka poem, the words I have reproduced, at least in essence, were said by Mam’Dorothy and the other artists in conversation with her at Sophiatown the Mix. It was likely the last singing performance she gave, and I am honoured to have been there. I want to note that Mam’Dorothy said that evening, as I have included toward the end of the poem, that Zimbabwe is not her land, simply her place of birth. This is an idea I am asking, in different ways throughout the collection, South Africans to reflect on.

The JRB: Finally, when you signed my copy of IGoli/EGoli, you dedicated the poem ‘Natalia Molebatsi and Bab’Themba Mokoena in dance’ to me. Thank you! Please tell me about the influence of poets and musicians in your work and your life.

Salimah Valiani: I love all you poets and novelists and painters and sculptors. You bring out the subterrain, the interiors, the hidden of our lives and our world. I am inspired by other artists and try to hold the moments they create by conceiving of poems, and sometimes other art, that add to, embellish or underline their brilliance.

The JRB: How would you like to end our interview? With a poem, perhaps?

Salimah Valiani: Poetry is always a good beginning and ending. So here goes, a new love poem:

On love

the day your love in Jozi

makes pizza with the dough you left her and

forgets the sauce a spirited stranger in Calgary says

with the warmth of the Shanghai cab driver and

so many Joburgers

not just Hello

How are you?

but even Thank you when you reply

and you know

we are finding one another

in a wide world whispering One

- Anna Stroud lives and writes in Melville, Johannesburg. Follow her on X or Instagram.