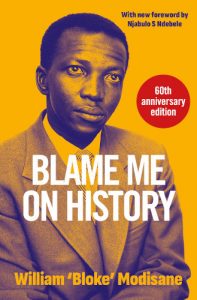

The JRB presents Njabulo S Ndebele’s Foreword to the new sixtieth-anniversary edition of William ‘Bloke’ Modisane’s Blame Me on History.

Blame Me on History

William ‘Bloke’ Modisane

Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2024

Foreword

Njabulo S Ndebele

‘My physical life in South Africa had ended.’ The last sentence in Bloke Modisane’s Blame Me on History begins this foreword. It also concludes the last and only chapter in the book that has a title, ‘Postscript’, rather than a chapter number. In the same way that this book evoked so many of my childhood and teenage memories of the 1950s and 1960s, the word ‘postscript’ also called up some nostalgia.

In the practice of our parents and grandparents before us, my generation of hand writers would write ‘P.S.’, for ‘postscript’, at the end of a letter already signed. This was a useful device to signal the addition of an afterthought and avoid having to rewrite an entire letter by hand. The practice died out with the advent of word processors such as WordPerfect—in their turn decimated by the likes of Microsoft Word. In the same way, Blame Me on History recalled for me sensory childhood memories of location life in the second half of the 1950s and in my early teenage years during the 1960s. South Africa has changed a great deal since then. What would it be like to read this book in today’s South Africa? This is a question that can only be answered by readers who place this latest edition in their hands and turn its pages.

As I turned the pages of my father’s 1963 edition of Blame Me on History, numerous feelings and thoughts erupted in me through the shifting boundaries of time. To begin with, I recalled that in the first half of 1969, the year I turned 21, I read my father’s now-lost 1959 hardback edition of Down Second Avenue by Es’kia Mphahlele, and immediately thereafter Blame Me on History. These were two among several banned books that my father hid in a wooden box in the garage at home, a story I have told in the preface to another book. The copy of Modisane’s original hardback survived for me to read it again.

Writing this foreword in 2023 is a fortuitous moment for me to recall this personal, book-length reading connection I established 54 years ago with two of the most influential Drum writers of the 1950s. Adding to this recall is the emotional resonance of reading about Mphahlele’s memory of his last moments in the land of his birth before he departed into exile in Nigeria.

‘Just before I boarded the plane at Jan Smuts Airport,’ Mphahlele recalled, ‘my friend, Bloke, said to me: “If you ever feel you want to come back, Zeke, take lots and lots of booze to work the urge out your system.”’ At different times and in different ways, the two friends and colleagues ended their ‘physical lives’ in the country of their birth: temporarily for Mphahlele; permanently for Modisane.

A year and two months after the student uprisings of 16 June 1976, Mphahlele ‘officially returned’ to South Africa as he and his wife, Rebecca, landed at Jan Smuts Airport on 17 August 1977, her birthday. Modisane died in Dortmund, West Germany, on 1 March 1986. His remains rest far away from his country, the one which, on every day of his life living in it, had assaulted his sense of self and of home.

I sensed too that Modisane’s last words to Mphahlele would, at that very moment, have rekindled memories of shared speech mannerisms developed and evolved in the newsroom of Drum magazine, which pulsated with the lively, professional camaraderie of the stimulated minds of journalists who loved to write what they spoke, and to speak what they wrote. One could call the language culture of the magazine’s newsroom ‘Drum speak’. In such a context, the word ‘booze’, used by Modisane and Mphahlele at that emotional moment of parting, would have evoked shared experiences of ‘nice time parties’ in shebeens they may have patronised, or in one another’s homes, where they may have enjoyed some hard liquor, albeit anxious that if they did not have a permit to buy such liquor, they risked arrest by police.

Mphahlele describes the Drum style as ‘racy, agitated, impressionistic, it quivered with a nervous energy, a caustic wit. Impressionistic because our writers feel like at the basic level of sheer survival, because blacks are so close to physical pain, hunger, overcrowded public transport, in which bodies chafe and push and pull.’ Of Todd Matshikiza, journalist and composer, Anthony Sampson writes: ‘Todd transformed Drum. He wrote as he spoke, in a brisk tempo with rhythm in every sentence. He attacked the typewriter like a piano. Our readers love “Matshikese”, as we called it, which was the way they talked and thought, beating in time with jazz in them.’

Mike Nicol may have had this kind of ‘Drum speak’ in mind when he observed that Drum writers, modelling themselves after American writers and movie stars, would have Casey Motsisi writing, ‘“By the way, pardner, let me introduction you” when he meant “introduce”. Or their highly inventive imaginations would call plain-clothed policemen the “ghost squad” or prostitutes “night specials”.’

To Mphahlele, Modisane’s parting appeal to him could have meant, ‘My friend, at those searing moments of nostalgia, do what we have always done back home: booze up.’ Modisane’s advice could well have been accompanied by a naughty wink and, in return, by Mphahlele’s knowing, mirthful laughter.

This parting of Mphahlele and Modisane fondly reminds me of Modisane’s own last moments at Johannesburg’s Park Station just before the train took him away to Botswana (then Bechuanaland). Among those on the platform to see him off was ‘faithful friend, Lewis Nkosi, the boy I had privately and unofficially adopted as brother’. Here was another parting of Drum friends. This time there would be no friendly advice for the departing friend from those remaining.

Their last shared memory was an incident at the station kiosk. To escape the awkwardness of the tension among the small farewell party, which included his wife, Fiki, and their daughter, Chris, Modisane decided to go with Nkosi to buy a packet of cigarettes. At the kiosk, ‘two Afrikaner women went on talking together deliberately ignoring my presence’. This was one of the last memories of the banality of white racism that Modisane took away with him.

Because I read their books one after the other, I also remember that each book affected me differently. Mphahlele’s autobiography flowed more easily as a story told with a page-turning pace. Blame Me on History, on the other hand, was more demanding, requiring me to read it slowly, stopping to ponder as I read on. This book was no page-turner for me, a high-school graduate about to travel to Lesotho to begin undergraduate studies.

Looking back, I realise I had yet to be initiated into Modisane’s kind of analytical narrative, its powerful drama fused with its cerebral yet emotional writing. I think I missed the extent to which he unsparingly revealed himself to his readers and his deeply self-conscious relationship to the world around him. Into this was built mutual racial hostility, a violent township and family strains, which reduced his marriage to Fiki Plaatje to a partnership of loveless tolerance. Modisane partly blames a class-based ‘snobbishness’ in his wife, ‘which perhaps was responsible for the relationship with Ma-Willie [his mother] who was a shebeen queen’.

The undergraduate and graduate parts of my long initiation towards a second reading of Modisane, 54 years later, took me through, among others, Ayi Kwei Armah’s The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born (1968), Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952) and Albert Camus’s The Stranger (1942). The undergraduate literature syllabus was varied. For the first time, I read and studied the writings of Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Christopher Okigbo, Ousmane Sembène and Mongo Beti, as well as some of the more traditional English literature offerings.

Blame Me on History would yield its full pleasures to me much later in my intellectual life. But I also know that the rediscovered pleasures were founded on the experience of having ploughed through the entire text at a time when something I did not fully understand nevertheless pulled me on to the end, perhaps extending, without my knowing, the capacity of my mind to wrestle with complexity. Two books I read at university in Lesotho were my light bulbs: Camus’s The Stranger and Ellison’s Invisible Man. Something rang familiar about their very different main characters: a self-consciousness that could come across as detached in Camus’s character or insightful and complex in Ellison’s.

An understanding crystallised at post-grad level in Cambridge when, as part of my long essay project, I chose to study the writings of Fyodor Dostoevsky. I now found Camus’s character Meursault rather remote, despite, or perhaps because of, his being too engrossed with himself. It was when I read Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground that I recalled, even if dimly, the resonance of Modisane’s pitiless, critical self-awareness and innermost probing of self, whose fullest implications may have been above my understanding in 1969.

Some of the relevant highlights in my graduate work included readings in the stream of consciousness as a literary technique, taking me through a ponderous yet increasingly absorbing James Joyce in Ulysses, while Notes from Underground floated frequently into my mind as I reread Modisane. It was clear from his public journalism that Modisane, while far from being ‘underground’, was never free of the daily stresses of being above ground. Rather, it was his country, in its hostility to him and his kind, that drove him, and millions of others, into a fear-ridden inner world of debilitating self-awareness and powerlessness, which had them continuously simmering with rage. They were driven to obliterate their inner selves even as, and probably because, they were so unavoidably visible to a powerful and violent white political and social order that hated the sight of them even as it could not do without them.

But the agonising details of Modisane’s inner life triggered much more of my curiosity than did Dostoevsky’s ‘Underground Man’ in Russia, or Camus’s French character in colonial Algeria. With a second reading of Blame Me on History, this time for this preface, I was so much more intrigued by Modisane’s unravelling of his inner self in his autobiography that I began to ask questions about myself, the reader, who was confronted this time with a much more familiar African man, with whom I have shared an anguished country. If this was Modisane in the 1950s and 1960s, who was I today? Who are we South Africans today? These are questions that may arise for other South African readers.

But in 2023 I could now also find in Modisane’s autobiography epiphanic moments I had missed despite there having been so many. I could now clearly see how Modisane revealed his inner agonies, the burdened self-consciousness of an oppressed, gifted, sensitive, educated black man living in the depths of the political, economic, social and legal hell the apartheid ideology imposed, differentially, on the peoples of South Africa.

Yet there was always the gift of resourcefulness available to enable survival—not just to keep breathing but also to develop the level of intelligence with which to beat the white system at its own game. Today’s sophisticated looting of Eskom may have a long history of anti-system inventiveness now flying on autopilot, wreaking havoc in a new state that needs rigorous and committed nurturing from every South African. It is a kind of self-destruction that lacks, and may desperately seek, the redemptive power of Modisane’s often brutal self-awareness.

Modisane employs detailed recall to take us through the hell in which he nevertheless does not allow us to drown. Certainly, part of the hell was the brutal destruction of Sophiatown, a destruction that was to him a murder. Like many other acts of violence around him, a murder would remind Modisane of the way his own father had been battered to death: ‘Sophiatown was like one of its own many victims; a man gored by the knives of Sophiatown, lying in the gutters, a raisin in the smelling drains.’

But Modisane also found beauty in his community: ‘Whatever else Sophiatown was, it was home; we made the desert bloom; made alterations, converted half-verandas into kitchens, decorated the houses and filled them with music. We were house-proud. We took the ugliness of life in a slum and wove a kind of beauty which set a pattern of communal living, far richer and more satisfying—materially and spiritually—than any model housing could substitute. The dying of a slum is community tragedy anywhere.’

This takes me back to ‘Postscript’, the summative last chapter of Modisane’s autobiography. It is no less than a meditation on ‘the law’, whose essential meaning in South Africa at the time Modisane describes: the ‘standard of this law is white, its legislative authority is white, its executive authority is white, and as a black man I had to adjust myself to it though I accepted it as unjust. The discriminations are written into the law, to protest against the discriminations is to be produced against the authority of the law. I see South African law as the basis and instrument of my oppression. I am black, the law is white.’

From 1948 until the advent of democracy in 1994, ‘the law’ in South Africa authorised apartheid’s tangled banality: the lawlessness of its laws, designed as they were to control and use, at the whims of the white state, black people as the universal instrument of labour whose muscle would build the glittering edifice of white South Africa into what it became and continues to be. A daily assault on the humanity of black South Africa, ‘the law’ manufactured violence both in enabling white control of black people and in black people’s resistance to that control. Often the violence would flourish among the township dwellers themselves, who let it out among themselves in a continuous assault on their shared humanity. Today, South Africa is still experienced by many of its own citizens as a violent country.

The last paragraph but one of ‘Postscript’, the very last chapter of Blame Me on History, reads like a parable. It is a horrifying vignette of the way ‘the law’ in South Africa deformed the humanity of all its peoples. It is better read in the book than quoted in a foreword: the last paragraph but one.

Modisane’s book, read today by all South Africans, will expose our raw pasts, private and public in their nature, which are still present in many forms as unacknowledged antecedents. Indeed, this time, many years later, engrossed and fascinated, I turned the pages of Blame Me on History as fast as I could.

~~~

- William ‘Bloke’ Modisane (1923—1986) was a South African author, playwright and actor who worked on the staff of Drum magazine in the nineteen-fifties. He emigrated to Europe in 1959 and died in Dortmund, West Germany, in 1986.

~~~

Feeling an exile in the country of his birth, the talented journalist and leading black intellectual William ‘Bloke’ Modisane left South Africa in 1959. It was shortly after the apartheid government had bulldozed Sophiatown, the township of his childhood. His biting indictment of apartheid, Blame Me on History, was published in 1963—and banned shortly afterwards.

Modisane offers a harrowing account of the degradation and oppression faced daily by black South Africans. His penetrating observations and insightful commentary paint a vivid picture of what it meant to be black in apartheid South Africa. At the same time, his evocative writing transports the reader back to a time when Sophiatown still teemed with life.

This sixtieth-anniversary edition of Modisane’s autobiography serves as an example of passionate resistance to the scourge of racial discrimination in our country, and is a reminder not to forget our recent past.