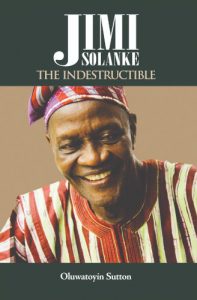

Sanya Osha pays tribute to the late Jimi Solanke, and chats to Oluwatoyin Sutton about her book Jimi Solanke: The Indestructible.

Jimi Solanke: The Indestructible

Oluwatoyin Sutton

Bookcraft Africa, 2023

Jimi Solanke’s artistic practice evolved in the decade following Nigeria’s political independence, when hopes were high and opportunities abounded. His multiple creative engagements reflected this sea of possibilities—so much so that he could be seen as the nemesis of any biographer, given the astonishing range of his activities.

Solanke, a prodigal in every sense of the word, died on 5 February, 2024, at the age of eighty-one. A singer, dancer, public jester, actor, mythologist, painter, folklorist, narratologist and teacher, he sometimes seemed to fall victim to his many gifts. But he also knew how to use his lavish sense of humour to defuse the extravagance and excess that were often associated with him. It was as if he was aware that his prodigality could be a source of shame or discomfort, and so he created endless opportunities to deflect and laugh it off.

By contrast, Oluwatoyin Sutton’s Jimi Solanke: The Indestructible, released less than a year before its subject’s passing, rehabilitates Solanke as a serious artist. As a performer, Solanke appeared in many of Ola Balogun’s films, and in the dramatic productions of Wole Soyinka and Ola Rotimi. He acted in popular television dramas, and as a storyteller he enriched the budding imaginations of children with several folk tales that drew heavily on communal wisdom and indigenous moral codes.

Perhaps an old Yoruba folk song named ‘Ojo je’, rendered by Solanke in his inimitable way, best captures the depth and power of his voice and soulfulness as a performer. ‘Ojo je’ encapsulates the unfathomable breadth and mystery of existence and the necessity to share Mother Earth’s gifts freely, having been blessed by her abundance. The song, lunging out of visceral depths, evokes the wonder of birth and the sorrowful dirges that accompany death and reincarnation, and embodies a melancholy similar to the delta blues of America’s deep South. Solanke’s art springs from this awe-inspiring existential and swampy chasm. Though he often tried to downplay its significance, the seriousness of his art broke out, in spite of his luminescence, boyish charm, and the sincerity of his disarming smile.

Indeed, as an avuncular presence with a rich, resonant baritone, Solanke was a cross between a divine, slightly off-kilter trickster and a mischievous court jester. That radiant grin of his was simply unforgettable. He embodied wide polarities of creativity in a bewildering manner. And yes, his profusion of gifts was such that it was sometimes difficult to take him seriously. He did not encourage his admirers to take him in earnest, aiming instead to remain simply ‘Uncle Jimi’, a folk hero, loved by many, derided by quite a few, with a joie de vivre some found annoying. How dare he live and love so freely?

From a marketer’s point of view, he must have been a nightmare. The manner in which he blithely broke down genres, defied corporate imperatives and expectations, and pursued extremes of artistic liberty wasn’t something the entertainment industry was built for. Instructively, he ditched pursuing a possibly lucrative career in Los Angeles because he wouldn’t participate in the cocaine culture that was prevalent at the time. He was both a puzzle and a headache.

Solanke’s range, experiences and cultural connections make for a baobab-scale branching out into West African cultural history. Due to his wanting to pursue his interest in the arts, particularly music, as a boy, his father sent him away from the bright lights of Lagos to live with a well-off uncle in Ibadan (Nigeria’s third-largest city, after Lagos and Kano). There, Solanke had more room to explore and develop his creative gifts. Hooking up with Afrobeat pioneer Orlando Julius, he began a formal apprenticeship as a singer by working with the likes of highlife greats IK Dairo, Eddy Okonta, and numerous other artists who either passed through or inhabited the great West African culture hub that was Ibadan.

But Solanke called Ile-Ife, the famed mini-city considered the metaphysical abode of the Yoruba, his spiritual home. Rich in cultural and spiritual lore, Ife remains mystical, slightly remote, retaining more secrets than it is willing to reveal.

Solanke had two major professional stints at Ife, between 1969 and 1972 and between 1982 and 1986, which is when, respectively, he worked at the Ori Olokun theatre collective and the university. Solanke did not become a permanent Nollywood fixture like his great theatre and movie contemporary, Sam Loco Efe, who eventually dominated the film hubs of Lagos and Onitsha. Instead, Solanke seemed to retreat into community service and cultural development—often involving children. He became the custodian of a deep-rooted cultural practice that mostly shunned commercialisation and corporate flamboyance. Perhaps this is what accounts for his limited forays into Nollywood’s frenzied and creative ferment.

At the Ori Olokun theatre, he was assistant director to Ola Rotimi (drama), Akin Euba (music) and the South African-born Peggy Harper (dance and choreography). Before this formal and elaborate apprenticeship, he gigged as a professional musician with highlife greats Roy Chicago and Chris Ajilo, in addition to the aforementioned IK Dairo and Orlando Julius. And all of this was behind him by his mid-twenties.

In his latter years, Solanke’s voice was weathered, yet his eyes continued to bulge with fire and defiance when he sang, mostly Yoruba folk songs. As noted earlier, ‘Ojo Oje’, his achingly beautiful rendering of the old Ile Ife folk tune, captures the bittersweet ironies of existence with bluesy depth. The haunting composition unveils the beauty and textured dimensions of Solanke’s voice, sheds his perennial comedic persona and points to a vast metaphysical unknown.

An archetypal showman forever betrothed to good times, Solanke was, as Wole Soyinka said, a son of the oracle, omo awo—a term of endearment meant only for proven initiates of esoteric cults. Soyinka further added that when the electoral crises struck the Western region of the First Republic of Nigeria during the turbulent nineteen-sixties, Solanke was often tasked to handle missions of a delicate and subversive political nature, during which he always acquitted himself admirably.

Solanke’s performance in Rotimi’s Ovonramwen Nogbaisi, which focuses on the tragedy of the modern sacking of the ancient kingdom of Benin in 1897 by British colonial adventurists, was so heart-wrenching that the Oba (king) of Benin asked that the production should cease; such was the depth and intensity of Solanke’s performance—which also netted him a post in the then Mid-western Region Arts Council under the patronage of Governor Samuel Ogbemudia. Solanke spent almost three years in that position, until he was invited by the late Professor Dapo Adelugba of the University of Ibadan’s theatre arts department to join the cast of Langbodo by Wale Ogunyemi. Langbodo, an influential dramatisation of DO Fagunwa’s Ògbójú Ọdẹ nínú Igbó Irúnmọlẹ̀ (‘The Forest of a Thousand Demons’) was Nigeria’s entry for Festac ’77, during which Solanke delivered yet another superlative performance, etching his name in the Nigerian public’s consciousness indelibly.

With funding from Unicef, Solanke was able to stage dramatic productions in the rural south-west of Nigeria, following his personal mission to service the arts at grassroots level. He channelled the same energy into forming deep relationships with thespians, colleagues and friends, many of whom later attested to his extraordinary efforts. Despite his peripatetic life, with stints in Lagos, Ibadan, Ile-Ife, Benin, London, New York and Los Angeles, he had several children, although he couldn’t, for the most part, have been a hands-on parent. His wife, Toyin, admitted he wasn’t always easy to live with; she had to draw on copious reserves of patience in order to endure his more erratic episodes. His home, in Ipara Remo, south-west Nigeria, is filled with sculptures and visual art he made in his spare time. There is a huge photograph of South African jazz musician Hugh Masekela. Clearly, he was a spirit enthralled by beauty in all its artistic forms.

In Jimi Solanke: The Indestructible, Sutton shows Solanke to be a formidable artist worthy of critical scrutiny, notwithstanding her subject’s tendency to undercut himself. The book also covers in detail the major signposts of his life and career. I asked Sutton to elaborate on a few specific points from Solanke’s biographical narrative.

Sanya Osha: Why wasn’t Solanke able to make a considerable impact in Nollywood?

Oluwatoyin Sutton: This is a good question, addressed at length in the biography. At a fundamental level, Jimi was a theatre man. He was trained in classical stage acting by people like Professor Wole Soyinka and mentors like Ralph Opara and Femi Johnson. Alongside Wale Ogunyemi, Yomi Obileye and co., JS was one of the first cohort of university-trained actors from the school of drama at the University of Ibadan in 1963-64. It was a craft he loved and excelled at. He dabbled in celluloid briefly in the nineteen-seventies (which is examined in detail in the book) and was in the earliest examples of Ola Balogun’s first films. In the late nineteen-eighties, the home video industry was emerging, as 35mm celluloid gave way to the cheaper, quicker and more accessible forms of film technology. Many of Solanke’s contemporaries on stage—practically all of them, in fact—made the transition to Nollywood. Solanke made a couple of attempts but hated the experience intrinsically; in particular, the many takes, waiting on location and the prolonged experience of filming, often filled with technical hitches in those early days—these did not sit well with him. The experience of acting with a live audience in a theatre was always the ultimate definition of how he perceived himself as an actor and theatre professional. He called it ‘serious acting’. He chose not to pursue Nollywood. It was a considered and deliberate decision made in the late-eighties. For him, it was simply about the principle of acting. He stuck to this decision tenaciously, even as many of his peers carved new celebrity careers.

Sanya Osha: What was Solanke’s relationship like with Sam Loco Efe, the late, great Nollywood actor who worked with him on Wale Ogunyemi’s Langbodo during Festac ’77? They were similar in many ways and yet towards the end of their careers their paths diverged widely.

Oluwatoyin Sutton: Loco Efe, only three years younger than Solanke, was a well-loved friend and contemporary. I got the impression that Efe felt the same. They were, as you said, similar in a couple of ways—especially when JS was younger.

From Jimi:

‘I had a great relationship with Sam Loko till he passed on [in 2011, at the age of sixty-seven]. We met a long time ago while I was at the Midwest Arts Council.

‘We were always at the MTV premises, where all great artists in Benin gathered in those days. Good, great times.

‘We both worked on Langbodo for Nigeria’s drama entry for Festac, under the direction of Prof. Dapo Adelugba.

‘Long after Festac, when I was a consultant for Unicef, using drama to sensitise the grassroots on their programmes, I invited Sam Loko to work with me leading the acting team that I dispatched to the Bendel axis.

‘We were great pals.’

As to why their paths may have diverged, as you alluded to, I can only surmise that Efe threw himself into Nollywood and JS did not, for reasons explained previously.

Sanya Osha: Do you think marital life might have curbed his creative flight as an actor?

Oluwatoyin Sutton: The answer to this question is a resounding no. However it requires further elaboration. Jimi got married in 1983 and started a family the year after. He was at the University of Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University) with Professor Soyinka as a drama instructor. When he left in 1985, there were fewer stage plays in general compared to a decade earlier, and since he had made a decision not to do Nollywood, he pursued his music and children’s television instead.

- Sanya Osha, scholar, writer and author of several books, lives in Cape Town, South Africa.