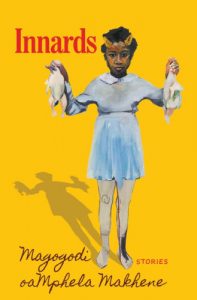

The JRB presents an excerpt from ‘7678B Old Potchefstroom Road’, from Innards, the debut short story collection by Magogodi oaMphela Makhene.

Innards

Magogodi oaMphela Makhene

Atlantic Books, 2023

7678B Old Potchefstroom Road

They came riding cattle lorries. Their whole world travelling with them, herded onto truck flatbacks. Thick woollen blankets folded into warm wishes. Matching chairs and lorry-scratched dining tables bought piecemeal on layaway. And head-scarved Granny, wrapped at the waist in a brown plaid blanket that doubled as cot when the baby fussed.

Out, those cattle wagons drove. Out. Past the city, Park Station behind them and old Ferreirasdorp decaying with the sunset. Out, meandering with Commissioner Street beyond an empty yellow wasteland dumped by Crown Mines. Out and into a barren veld bordered on either side by municipal sewerage farms.

They came like that, curious about this place. Curiouser still—entire families and their lives packed into the same space where a lamb probably hoof-kneaded sheep shit on its way to the slaughterhouse yesterday. The lorry beds were all metal and wooden plank, with mesh cage roofs like a chicken coop. Swine haulers, those lorries, now overloaded with babies, steamer trunks and loose cupboard drawers. Everything unhinged.

I wasn’t sure which family was mine. And by the standing around and waiting, pointing at numbers, eyes searching, these natives themselves seemed uncertain which of us was whose.

A short man with an orange moustache and a squat face took control, clipboard in hand, a neat row of pencils peeking from pocket. ‘Yebo Baas,’ the men answered him, showing their dompass. The Baas then gave each man a key with his number. Some slipped a few shillings into his hand for another number promising an indoor toilet. Then they packed off for this house. A thin mattress balancing on the wife’s head. A heavy washtub carried one-one on either side by the children.

—7678B? Clipboard Baas called my name. A man in a dark suit walked toward me, his wife behind—her white heels stepping into his imprints, so that their soles cleaved to one another in the dust. The children’s weren’t far behind. Stop, Granny shouted, Stop! Stop that running! But the mother was running, catching her husband’s shadow and moving past him, toward me. He watched her; let her. So that a woman first entered my threshold.

Her heels were soiled by now, the colour of rust, but she didn’t notice, running into my rooms, thrusting windows to the world, standing with her arms the width of my walls. As if embracing my full girth, everything inside me. As if to say, Yes. This will do.

Only with her children also running in and out of the rooms—rooms so small they could be folded up and stuffed into the lorry-fastened wardrobe—only then did the dirt floor disappoint her. Little feet kicked up dust and stone. The wife looked around, shushing the children, but her gaze met her husband’s and the steady smile growing on Granny’s face. We’ll have to plaster, she said. And … paint.

Men arrived. In long trousers that sat low, far low, below bare chests and taupe sweat. Ethel—I know her name now—Ethel hummed as she cooked, knifing tenderly through gummy seeds, fingering small tastes to her tongue. The smell of fried onion skin sizzling in sunflower oil and ripe tomatoes filled me, as if I were lungs.

She brought a tray out to the men. The tray held a small washbasin with soapy water and a clean cloth. Next to this was a large dish offering last night’s leftovers fattened with fresh tomato gravy. Ethel bent to pass the cloth and washbasin around, putting the food on the ground. Bodies close, she smelled how the sun made itself rancid on the men’s skin. She wound her neck—slowly, absently. When she took her lunch inside with Granny, her fingers caressed her nape just as absently, the same space between neck and spine that Tom’s hands and tongue had chiselled smooth late last night.

—It’s quite tasty, Granny said.

—Yes, Ethel smiled, e monate.

Tom—Ethel’s husband—was the sole sound I heard whispering to the night. It was quiet. Ethel was quiet, nervous their hunger would stir the children. She forced her pleasure into the pillow. A pleasure as silent as muffled pain.

—Have you heard the one about the Boer and his missus? Tom asked.

—No, she shook her head, gently, as if a full head shake would wake the baby beside them and the children on the now plastered floor.

—The missus, said Tom.

—Asks her Baas …

Tom stopped. Chuckling.

—That’s how krom daai man is, he says, still laughing.

—He orders his wife call him Baas!

Ethel smiled, wry. I could see her bare teeth flash at the asbestos roof that is my own mouth.

—Anyways, Tom goes on, the missus asks her Baas: But where were you, just now getting in, so vroeg in the morning? Where did you spend the night? The Boer scratches his head a bit and thinks quick on his feet:

—Ag, man, vrou! the skelm begins. Woman! I was at that friend of you’s. Susanna.

Go on, the wife’s face seems to say.

—Well. Her husband took a turn. For the worse. And just like that … Poop! He snaps a finger. The hairy bliksem died. He’s dead! The Boeremeisie sniffles. You know how you women are. Seeing this, the Baas is bloody chuffed with himself, swelling at his stupid cleverness. He doesn’t even notice his missus scratching about till she’s fully dressed, fetching her gloves and looking for a scarf to cover her head.

—Vrou? he asks. Waarheen nou?

—To Susanna’s, the missus replies. She’ll need to borrow you another night and maybe some other things also.

—Nee man! says the Boer, quick-quick on his feet, again scratching that head.

—They ring while you dressing. Turns out that old fat bastard isn’t dead after all. He rose. Up! Just now-now. Like Jesus! He rose up from the dead!

Ethel put a finger to Tom’s lips, stifling their giggles. She peered over his body at the young ones, sleeping below the mattress. Little chests rose and fell with the deep breath of children’s dreams.

More families arrived, taking up the empty numbers all around me, until the neighbourhood pulsed with fat gossip at communal taps, with hammering nails shouting response to workmen songs. Radios belted out news from faraway places where news happens—places so scary the fear seeped through the speakers and settled beneath my trenched roots. Stray chickens wandered in. Flocks of ashy children pecked about the street in grey packs that smeared their idleness and wonder everywhere people sprouted. Life grew without record or resolve. Daily routine—sewerage bucket dumps early mornings and coal deliveries before sunset—made rhythm out of time.

~~~

- Magogodi oaMphela Makhene is a proudly Soweto-made soul, who now makes her home anywhere with sunshine and writing space. An Iowa Writers’ Workshop alum, Magogodi is a Caine Prize, Hedgebrook, MacDowell and Rona Jaffe Award honoree. She leads immersive courses and experiences at Love As A Kind of Cure, a social enterprise she co-founded to dismantle white supremacy.

~~~

Publisher information

This incendiary debut of linked stories narrates the everyday lives of Soweto residents, from the early years of apartheid to its dissolution and beyond.

Set in Soweto, the urban heartbeat of South Africa, Innards tells the intimate stories of everyday black folks processing the savagery of apartheid with grit, wit, and their own distinctive bewildering humour. Rich with the thrilling textures of township language and life, it braids the voices and perspectives of an indelible cast of characters into a breathtaking collection flush with forgiveness, rage, ugliness, and beauty.

Meet a fake PhD and ex-freedom fighter who remains unbothered by his own duplicity, a girl who goes mute after stumbling upon a burning body, twin siblings nursing a scorching feud, and a woman unravelling under the weight of a brutal encounter with the police. At the heart of these stories about deceit and ambition, appalling violence, familial turmoil, and love is South Africa’s history of slavery, colonisation and apartheid. Innards’s characters must navigate the shadows of the recent past alongside the uncertain opportunities of the promised land.

Full to bursting with life, in all its complexities and vagaries, Innards is an uncompromising depiction of black South Africa. Visceral and tender, it heralds the arrival of a major new voice in contemporary fiction.