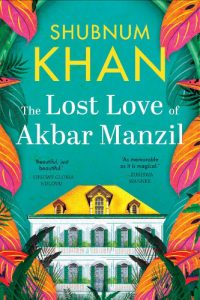

The JRB presents an excerpt from The Lost Love of Akbar Manzil, the forthcoming novel from Shubnum Khan, which will be published in South Africa in January. It will be published as The Djinn Waits a Hundred Years in the United Kingdom (February) and United States (January).

The Lost Love of Akbar Manzil

Shubnum Khan

Pan Macmillan South Africa, 2024

Prologue

1932

In an old wardrobe a djinn sits weeping.

It whimpers and murmurs small words of complaint. It sucks its teeth and berates the heavens for its fate. It curses the day it ever entered this damned house. It closes its eyes and tries to imagine a time before it came here, before it followed the sound of stars from the shore, before the world turned dark and empty.

Something thuds somewhere and the djinn is drawn from its misery by a commotion happening outside. It stops to listen and sounds begin to emerge; doors bang, windows shut, and things are thrown about. There are shouts as orders are given and people hurry through passages. They run up and down and bump heavy things along the stairs.

The djinn pauses, then it uncurls its limbs, swings open the cupboard, and steps out.

There is the patter of footsteps, then the front door slams downstairs and everything is suddenly still.

The djinn steps into the passage and looks around curiously. The floor is scattered with clothing and bedding. It wanders into the rooms; in a child’s bedroom, next to a smoking fireplace, twenty-seven plastic soldiers wait for a French army to advance. In a woman’s bedroom, a silk camisole slips off a swinging hanger in a cupboard.

The djinn creeps downstairs. In the kitchen, a dish of potatoes soaks beneath a dripping tap. Steam rises from a set-aside kettle. A basket of fresh laundry waits to be ironed.

The djinn wanders into the long dining room, among the high-backed chairs, and peers into the entrance hall where a grandfather clock ticks loudly. It pulls open the heavy front doors and looks into the bright, clear light of early morning. The stone stairs are strewn with opened trunks and scattered books. The driveway lies empty. The djinn steps outside into the pale pink light and looks to the still, shimmering ocean.

It turns to the looming house behind and wails.

One

2014

No one in Durban remembers a Christmas as hot as this.

The heat is a living breathing thing that climbs through windows and creeps into kitchens. It follows people to work and at queues in the bank and on trains home. It crouches in bedrooms, growing restless until at night in fury it throttles those sleeping, leaving them gasping for breath. It sweeps through the streets and bursts open pipes, smashes open green guavas, and splits apart driveways. It burns off fingerprints and scorches hair and makes people forget what they are doing and where they are going so that they wander around beating their heads. At the taxi rank in town people wave newspapers under their arms and wipe their foreheads with pamphlets that promise to bring back lost lovers. Witch doctors’ phone numbers drip down their temples and into their pockets in inky-blue puddles. Bananas blacken in the sun on pavement tables. The humidity grows and strangers are drawn to one another without meaning to and they cling together in a sweaty unhappy mess.

Out in the suburbs people sit in their inflatable pools with party hats and sip cheap wine from plastic cups. They eat bunches of litchis and hunks of watermelon and burn meat black on the braai. Maidless madams push hair out of their eyes as they hang up washing and count down to the end of the holidays. Dirty dishes pile up in sinks, garbage bags burst open with maggots.

At the coast the sky opens wide and burns the sea white. Little children in multicoloured swimsuits skip across the hot sand and shriek in thrilled agony. Families with pots of biryani and lukewarm Coke sit under small umbrellas fanning themselves with Tupperware lids as they dish rice onto paper plates.

The pier stretches on to eternity like a foreboding finger.

Sana Malek winds down her window and searches for a breeze. The dark curtain of hair flies off her neck to reveal her mother’s chin, and she turns this way and that as she struggles to make it her own. She is neither girl nor woman, hovering in that space between the two, where at the edge of her thoughts, curling at the eaves, is the glimpse of a fluttering light that promises something wonderful: a knowledge that the world is going to change.

She carries it close to her chest like a secret box.

She is going Home. It is not really home, but her father says it is because he believes it. He says Home can be many places, even places you haven’t been before. He says Home can also be a memory if you return to it enough. Sana wants to know exactly how many times you have to return to make a memory Home and her father says you will know when it happens.

Which isn’t really an answer but she accepts it anyway.

She accepts many things about him, like the fact that he lives by a collection of axioms of his making: Home can be a memory, rivers are more reliable than roads, and the ground keeps problems in. She accepts he will never be like the fathers she reads about, strong-minded and determined, wearing suits and cracking knuckles. She accepts that without her mother he has lost some anchor and like a ship he has strayed off into uncharted waters. And so when he announces one morning that he has finally found Home, she is not surprised and simply packs up and leaves with him in their Isuzu.

Since her mother’s death four years ago her father has become obsessed with coastal towns, marking cities along maps. He studies weather graphs and learns about the histories of towns along the South African coast. The west coast, he says, has many good things, like mussels and otters and small, wild roads, but it is cold and windy and there are too many white people. You can’t trust a place with too many white people, he says. The east coast has warmer waters, smoother stones, and a brighter sun—and warm places help you forget the past. They help you leave behind the painful things, he adds.

When they enter the city, the salt hits the air and a streak of blue skims the horizon. They work their way towards the ocean, passing little shops, conference centres, and brick buildings, and come to a knot of streets filled with graffiti, the smells of cooking food, and blaring foreign music. As they move past Nigerian pawnshops and Somali haberdasheries, African immigrants give way to Asian ones as Pakistani chicken tikka stalls emerge between Chinese fashion outlets. Farther down, Indian immigrants adjust the signs of their small spice stores, shift uneasily away from the crowds of new foreigners, trying to make it clear they are not as fresh off the boat. They tack signs onto their storefronts that say estimated 1918 and mutter about the good old days when everything did not come from China, when customers filled their stores searching for quality cloth and spices.

The secret box in Sana’s chest throbs. She is on the brink of womanhood and everything feels full and heavy with expectation; there are Discoveries That Are Waiting and Experiences to Be Had, and for a moment she allows herself the pleasure of wondering what a new life will be like.

Everything feels shivery and waiting.

‘I think we’re close,’ her father says, pointing to the small mosque with a green dome on the side of the street. He turns down a narrow road between apartment buildings that press so close together people can pass notes or pots between the windows, if they like. After a moment the tight buildings fall away and the land opens up around them.

They are driving up a hill along the ocean.

At the top they find a rusting gate, which she swings open for the Isuzu to pass. Ahead of them, in front of the driveway, stands a large house distorted by the shadows of the setting sun. Its windows seem to turn like empty eyes to watch them as they drive up.

Sana wonders if Home can be something that swallows you up. They turn into a gravel driveway, and in the last of the light Sana sees that the entrance has the crumbling stone letters ‘Akbar Manzil’ above it. She looks up and on the top floor she sees a figure: a girl outlined in the arched window above, watching them. Sana’s breath catches and she closes her eyes quickly. She tells herself she is imagining things, that she is just tired from the journey. That nothing can follow her here. She counts to ten and opens her eyes.

The window is empty.

She sighs in relief and jumps out of the car and begins helping her father off-load the luggage. As she heaves out bags, she hears the front door open. In a pool of yellow light in the doorway stands an old man leaning on a cane. He smiles, limping as he comes towards them.

‘Welcome!’ he calls out.

Behind him the lights in the house stutter and go off.

~~~

- Shubnum Khan is a South African author and artist. Her first novel, Onion Tears, was shortlisted for the Penguin Prize for African Writing and the University of Johannesburg Debut Prize for Writing in English. She holds a Master’s degree in English and has been selected for a number of literary fellowships, including the Octavia Butler Fellow at Jack Jones Literary Arts and as a Mellon Fellow at Stellenbosch University. When not travelling, Shubnum lives in Durban writing and drawing for a living.

~~~

Publisher information

Sana and Meena will never meet. The two women share little beyond Akbar Manzil, the sprawling mansion they call home. When Meena fell in love with the owner of the house, it was the grandest residence on South Africa’s east coast near Durban. Eight decades later when Sana and her father move to the house, the latest of Akbar Manzil’s long list of tenants, it is in near-ruins, crumbling, shabby and dark. This is a place where people come to forget. Or to be forgotten.

Full of questions about her new home, Sana is drawn to the deserted east wing, home to a clutter of broken and abandoned objects—and to the locked door at its end, unopened for decades. Soon, Sana begins to discover the tangled, troubling history of the house, awakening the memories of the house itself and dredging up old and terrible secrets that will change the lives of everyone—living and dead—at Akbar Manzil.

Sublime, heart-wrenching and lyrically stunning, The Lost Love of Akbar Manzil is a haunting, a love story and a mystery, all twined beautifully into one young girl’s search for belonging.

One thought on “[Fiction Issue] ‘No one in Durban remembers a Christmas as hot as this’—Read an excerpt from Shubnum Khan’s forthcoming novel The Lost Love of Akbar Manzil”