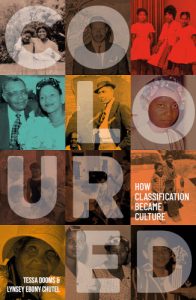

The JRB presents an excerpt from Coloured: How Classification Became Culture by Tessa Dooms and Lynsey Ebony Chutel.

Coloured

Tessa Dooms, Lynsey Ebony Chutel

Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2023

Awê! Ma se kind: Finding our mother tongues

By Lynsey Ebony Chutel

For all its comfort as a common tongue for many Coloured people, there is an ambivalence about Afrikaans itself, and its place in South Africa today. The role of Coloured people in the very creation of the language—both historically and in the present—is also contested. That debate finds itself within a much larger national conversation about language and a resurfacing of ethnicity that is increasingly looking to the past, challenging accepted historical narratives and the creation of South Africa itself. If we were to use language to create a border around identity and culture, as has sometimes been suggested to rectify colonial geographic and ethnic delineations, we risk robbing that language and its people of their history and nuance. Language does not evolve in a straight line, in logical steps: the people come first, and then come the grammar rules. Language stretches and contorts as people describe their experiences, and give names to things, places and feelings as they discover them. This, of course, is not a neutral process, and power shapes that creation of language, regardless of the discourse that stems from it. Often, it is the oppressor whose words prevail but, between the lines, the oppressed have subverted languages around the world. When we accept the victor’s tale or the loudest voices’ version of a language and its creation, language becomes a tool of othering, manipulating ethnic identities and histories to create an us and a them. The official history of Afrikaans has done that, making it the tool of the oppressor and ignoring its evolution as a language of subversion and necessity for the Africans whose tongues fashioned it from Dutch.

When Africans first began to speak Dutch, it was for the purpose of interpretation in the early naiveté of the relationship between Dutch traders and the Khoe. Among the first speakers was Autshumao, the leader of the Goringhaicona clan who lived on the beaches of the Cape coast and first encountered the settlers. Autshumao had learnt Dutch and English after travelling with English sailors to Bantam, an English colonial hub in the Philippines. On his return, his ability to negotiate with these new traders made him a rich man. But as the trade relationship continued to develop, the Khoe found that their transactions with the European traders were becoming increasingly lopsided. Here already, four centuries ago, the use of language tipped in favour of maintaining European power. There are few accounts of the Dutch learning the language of their Goringhaicona trading partners. Instead, in a world that was beginning to change irrevocably, the language that had created Autshumao’s advantage also left him isolated from his own people. Trade soon turned to war, and his relationship with the settlers did not guarantee him his freedom—his former trading partners exiled him to Robben Island, as one of that windswept island’s first prisoners.

This relationship also cost Autshumao his name. For centuries, his name has been forgotten, with colonial historians and, later, apartheid-era history textbooks simply calling him the derogatory name ‘Herry the Strandloper’. Even the recorded name ‘Goringhaicona’ was a mangling of !Uri ’ae ona. His fellow translator, Khaik Ana Ma Koukoa, was dubbed Claes Das, his name too complex for incurious European tongues. Autshumao’s niece, who also acted as a translator and became a doomed envoy between her people and the settlers, was named Eva. Her name was Krotoa, and the reclaiming of that name in post-apartheid South Africa has become a battleground for the retelling of the story of the Cape but also of the role of African women in those early years of colonialism.

The records we have of the lives of Autshumao, Khaik Ana Ma Koukoa and Krotoa are single stories, clerical accounts of their lives in relation to the Dutch settlers or the one-sided memoirs of ordinary, often mediocre, European men who have recast themselves as the heroes of conquest. Their stories are written in a language that was unable and unwilling to name and describe the dignity of the Africans with whom they came into contact.

We know little about the anguish of isolation they must have faced, the cultural schizophrenia of what we call code-switching today, as those first translators searched colonial Dutch for words to describe their culture, and their values. Anyone who speaks more than one language knows that language is more than syntax and grammar—proverbs are a short history, jokes are tales of survival, greetings are unifiers, and one gesture could be a whole poem. So much must have been lost in translation, and we feel that loss acutely now as we slowly start to understand that European languages overlook much of who we are as Africans. It is harder still for Afrikaans-speaking Coloured people, who claim a mother tongue that has tried to reject them, to recast itself as a White man’s language, denying its origins for the sake of the White supremacist project of Afrikaner nationalism.

As the Cape Colony took shape in the early seventeenth century, graduating from an outpost to a thriving city, Dutch was the lingua franca, reflecting the political and economic power structures already entrenching themselves into the soil of the Cape and which endure today. Yes, the French Huguenots were not permitted to teach their language, but their culture endured in part because of the long, written history of the French language as well as the innate social standing of the French refugees who came to the Cape. When the Dutch East India Company (VOC) brought enslaved people to the Cape from Angola, Mozambique, Madagascar and Indonesia, it forced each one to learn Dutch at the expense of the language of their homes. Those born at the Cape spoke only Dutch. By the early eighteenth century, the population of these Dutch-speaking enslaved people equalled the number of European settlers. In a life that allowed little dignity, fluency in the language of the master and the mistress was rewarded with a trite gesture that gave them some pride in a warped system: the enslaved peoples who were allowed to wear hats were the people—privately owned—who were deemed acceptable to serve in the homes of, or close to, their colonial overlords.

This loss—of names, places, histories and dignity—is why it is such a victory that South Africa is beginning to acknowledge that the language we know as Afrikaans today owes much to the enslaved people who spoke it. Much of the syntax, rhythm and even new words that differentiated Afrikaans from Dutch were formed in the mouths of enslaved people. It was the descendants of these enslaved people who printed the first Afrikaans text, in the eighteen-forties, written in Arabic script. As the language broke away from Dutch and defined itself, it created a unifying identity not only for a generation of European settlers born in the Cape, but also for the descendants of the enslaved Africans and Asians who had adapted to life in the colony, despite its hardships. Afrikaans also became the medium of instruction in the Muslim schools permitted at the colony, and the language of sermons in the mosques in the eighteen-fifties.

Still, this creolisation of Dutch into Afrikaans is one of several stages of the evolution of the language we know today. If adaptation and exploitation first necessitated the shift from Dutch, the Whitewashing of Afrikaans was driven by political power and White supremacy. There was a growing need among White settlers to separate themselves from the enslaved and servants—the Black and Brown people—who had quite literally built not only the Cape, but also the language that was now being used to create a sense of independence. This separation would require severing any ties between Afrikaans as an African European language and the enslaved people who created it.

As we’ve seen, to succeed, racism must create an us and a them, must separate master and slave and declare the superiority of one over the other. Academically, it isn’t hard to understand, but psychologically and emotionally there is a brutal intimacy to the racial violence and malice of the purification project. Imagine a group of people ripped from their homes, their families, their histories, robbed of their languages and their names. Now, picture those people raising the children, feeding the families and building the homes of their kidnappers and oppressors. Imagine, then, the resilience and creativity of these people, the ancestors of Coloured people, in taking a language used to subjugate and disempower them and turning it into something that is their own.

~~~

- Lynsey Ebony Chutel is a journalist and writer. She is a reporter for the New York Times and has worked for South African and international news outlets, along with stints in scriptwriting for an international Emmy-nominated news satire show. She holds a master’s degree in journalism from Columbia University and a master’s degree in international relations from the University of the Witwatersrand.

- Tessa Dooms is a Director at the Rivonia Circle. She is a sociologist, political analyst, and development practitioner with 15 years’ experience. She holds a Master of Arts from the University of the Witwatersrand. Tessa is a trustee of the Kagiso Trust.

~~~

Publisher information

Coloured as an ethnicity and racial demographic is intertwined in the creation of the South Africa we have today. Yet often, Coloured communities are disdained as people with no clear heritage or culture—‘not being black enough or white enough.’

Coloured challenges this notion and presents a different angle to that narrative.

It delves into the history of Coloured people as descendants of indigenous Africans and a people whose identity was shaped by colonisation, slavery, and the racial political hierarchy it created.

Although rooted in a difficult history, this book is also about the culture that Coloured communities have created for themselves through food, music, and shared lived experiences in communities such as Eldorado Park, Eersterus, and Wentworth. Coloured culture is an act of defiance and resilience.

Coloured is a reflection on, and celebration of Coloured identities as lived experiences. It is a call to Coloured communities to reclaim their identity and an invitation to understand the history and place of Coloured people in the making of South Africa’s future.