The JRB presents an excerpt from Maye! Maye!: The History and Heritage of the Kwa Mai Mai Market by Sipho Sithole.

Maye! Maye!: The History and Heritage of the Kwa Mai Mai Market

Sipho Sithole

Jacana Media, 2023

Kwa Mai Mai: Not your usual hostel

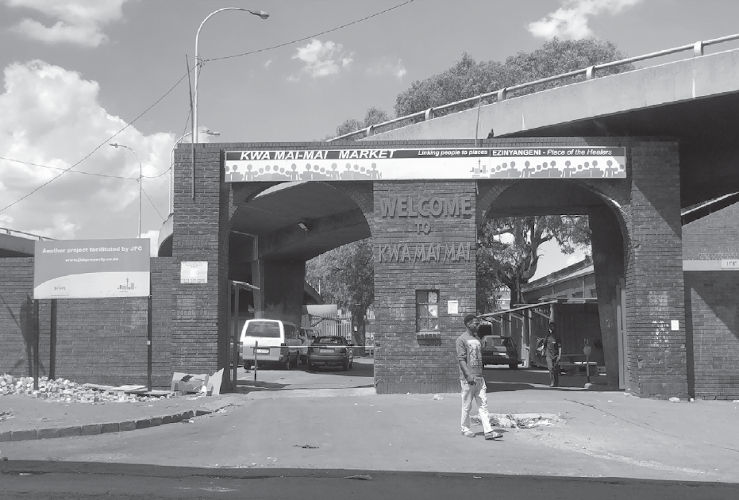

A sign above the gate saying ‘Welcome to Kwa Mai-Mai’ can mean different things to different people, depending on their cultural persuasion and emotional triggers.

In Zulu, kwa means ‘at’ or ‘place of ’, which can be used in an associative or possessive sense without attaching it to the full noun. When kwa is used together with Mai Mai, the name starts to become interesting. Because the name is used colloquially and not in a formal sense, it is easy to get ‘lost in translation’. Yet when it is applied properly and pronounced as Kwa Maye Maye, there is a spike in interest, especially among those who understand the language. Inevitable questions are posed: What really happened here? Why was this place given this name?

Imagine a place called Kwa Mshaye Azafe, which means a place where one is beaten to death. There are place names that denote some form of activity or inherent significance, as when Johannesburg is referred to as Kwa ndonga ziyaduma (walls that thunder) or Kwa nyama ayipheli kuphela amazinyo endoda (a place where meat is in abundance and only teeth wear out from eating it).

In Nguni, maye maye is an expression of shock, disbelief or exasperation, which will inevitably induce some awkwardness and discomfort in those who pass through the gate for the first time. Hearing someone down the street or a next-door neighbour screaming ‘Maye Maye’ or ‘Mai Mai’ could easily persuade you to call the emergency number. It can only mean that something is very wrong and needs the urgent attention of whoever must come to the rescue. As previously explained, it was popularly believed that ‘Maye Maye’ was the signature scream of a particular mine manager whenever there was an accident in the mine. The Salisbury and Jubilee mining compound could not rid itself of this name, and so, when the compound relocated to the current site, the name persisted.

Today, the new Kwa Mai Mai is sandwiched between Anderson Street, one of the nine oldest streets in Johannesburg, and Durban Street, which has no particular link to the city of Durban (located more than 500 km from Johannesburg). With everything under one roof, Kwa Mai Mai is a place where village migrants-turned-ethnic entrepreneurs have converged to supply products and services to clients, who include both tourists looking for souvenirs to take back to their cities or countries and those making a deliberate trip to look for items that only Kwa Mai Mai supplies.

Tucked under a bridge in downtown Johannesburg, and far from the gaze of economic hitmen and venture capitalists, is a place where culture, heritage and tradition (as championed by its residents) converge and find expression in the creative pursuits and cultural narrative of migrant workers who, once on the margins of society, have become ethnic entrepreneurs. The story of Kwa Mai Mai conjures up Marx’s notion of ‘man as a producer’, in that a migrant class has succeeded in elevating itself, through a major reorganisation, from a position of subordination to one in which it owns and controls the means of production.

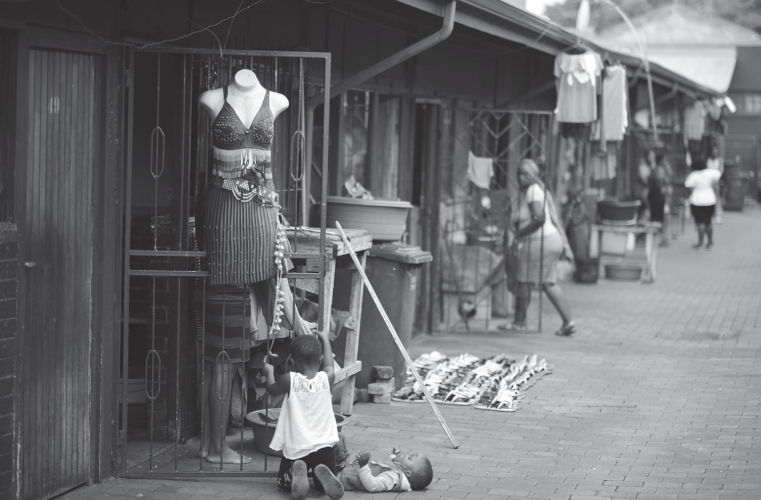

Beyond the gate is a busy cultural economy, built from the ground up by those from the edges of society who were rejected by the formal employment system. Not willing to go home and face the prospect of mockery and rejection in the villages as abashaywe iGoli (those who failed to make it in Johannesburg), they have created an economy based largely on a social system woven from their combined beliefs and traditions. It is a place that has become a refuge for those who left their villages to look for formal employment but soon abandoned the search when it became clear that such opportunities did not favour them. A determined group of ex-migrant workers took over a space that initially was the preserve of an elite, capitalist class, that is, a stable for the horses belonging to those who enjoyed privileged positions in society. With vision and ingenuity, a single-purpose stable was transformed into a thriving cultural hub.

There is something intriguing about the way in which Kwa Mai Mai has managed to survive and resist property developers who have combed most of Johannesburg in search of areas in which to establish upmarket trade zones, which would be partitioned off and rented back to traders at a premium. Refusing to succumb to the challenges of unemployment, poverty and inequality, this cultural market has also refused to be swallowed up by property developers eager to turn traditional African marketplaces into shopping malls, which would eventually disparage the very people whom these trade zones were designed to serve in the first place.

There is much more to Kwa Mai Mai’s socioeconomic character than meets the eye. Unlike ‘Chinatown’ or a market named after a homogeneous ethnic or racial group, Kwa Mai Mai constitutes a multi-ethnic group of South Africans bound together by the spirit of entrepreneurship and creative innovation, and embodies a community at work that has embraced the concept of vukuzenzele (self-help) and created an industry that has stood the test of time.

Kwa Mai Mai may not be a gated community such as those that characterise the lifestyle of so many in the northern suburbs of Johannesburg. There is no intercom for visitors to press or register to sign to be admitted through the gate. However, not a single visitor goes in or out unnoticed. Whether or not there are barriers to trading is determined by one’s ability to assimilate and accept the traditional leadership structures that have been in place at the hostels for decades. Some visitors come to Kwa Mai Mai not just to buy cultural goods; they are interested in the social structure or make-up of the place. However, unless one is coming to buy cultural goods or to consult with traditional healers or diviners, it may be necessary to seek permission for the visit from the induna (the headman). After satisfying himself and having consulted with isigungu (a committee that looks after the affairs of Kwa Mai Mai), the induna will either grant or deny access to a prospective visitor, depending on the nature of the permission being sought.

Kwa Mai Mai may not bask in the same light as other emerging collaborative hubs where culture meets business and entertainment is the tie that binds. It may not be in the same league as the creative enclaves of the privileged few, which are located uptown or downtown in places such as Maboneng or Braamfontein. It should also not be forgotten that these other cultural precincts have had their fair share of economic challenges. Precincts such as Maboneng, the Market Theatre and Braamfontein have experienced mixed success and have been subjected to severe economic buffeting. Because of urban decay and security concerns in downtown Johannesburg, all these precincts, despite their best efforts, have proved to be hard to sustain, within what is largely a problem of ‘location’.

What makes Kwa Mai Mai distinctive, despite its urban setting, is its all-encompassing character, which sees it alienating neither the marginalised nor the prosperous. In other words, it does not distinguish between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’. Having endured all sorts of socioeconomic challenges, Kwa Mai Mai has been around for seven decades—at least in its new location.

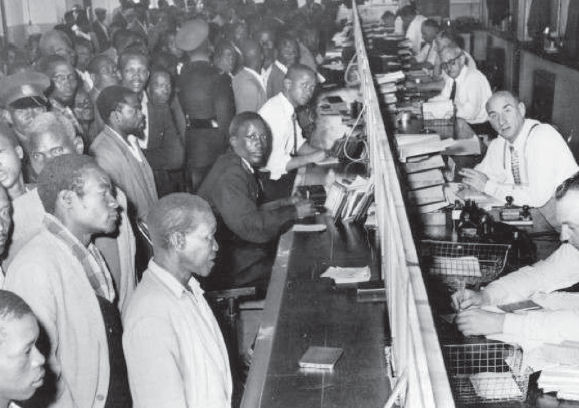

Fortunately, none of the traders and cultural entrepreneurs in Kwa Mai Mai are subjected—as they were in the past—to the long queues at the Bantu Affairs Department, originally a few blocks up the road, to obtain a permit legitimising their presence in the city. They are no longer the so-called natives seeking permission to enter, leave and work in Johannesburg. As Lauretta Ngcobo (1999:11) remarks in her book And They Didn’t Die, the residents and traders of Kwa Mai Mai have survived what she calls ‘the burial ground of all human dignity’.

Today, the residents and traders of Kwa Mai Mai are spared indignity and humiliation—at least at the hands of Europeans. Even those who frequent Albert Street to ply their trade as car washers and parking attendants for the more well-heeled (who typically reward these entrepreneurs with a paltry collection of coins), do not need to produce a permit.

Inside the Kwa Mai Mai compound is a group of proud villagers who have dug deep into their tradition and heritage to unearth the long-hidden treasures that make them truly unique and distinguishable from other urban dwellers. In the process they have discovered what in the villages was often taken for granted—the everyday life of a rural community who followed a daily routine and practised ancient rituals through the medium of dance and song, adorned in traditional garb and using simple, inexpensive artefacts to add to the display.

Determined to reimagine a new life for themselves in the postcolonial era, these villagers-turned-city dwellers have managed to build businesses on the strength of their belief in the economic value of a culture that for many years had been exoticised for the amusement of spectators. Escaping the margins of society, these urban villagers have entered a space traditionally reserved for merchants and traders of other races, who would typically operate as middlemen, employing migrant workers to produce cultural artefacts which they would then sell for a considerable mark-up, leaving the migrant workers out of the profit loop.

Kwa Mai Mai is unlike the popular road-side spots where street vendors crowd the city’s pavements, selling anything from sunglasses, belts and amagwinya (fat cookies) to cell phone chargers, fruit and vegetables. Rather, the thriving economy of Kwa Mai Mai has thwarted attempts to turn black city traders into small-time vendors of basic essentials. Kwa Mai Mai today is not only what, on the surface, looks like a trade zone for crafts, shisanyama, traditional medicine and herbs; it is also the epitome of how people, driven by a desire to beat the odds, have risen to the occasion and taken control of their own destiny.

Kwa Mai Mai has always been known for its herbal medicine, for the craftsmen who produce wedding kists and boxes for mineworkers to store their personal clothing and other items, for traditional garments made of skin or fabric, and for traditional fighting sticks and shields decorated with cow hide. As mentioned earlier, one of the items produced in Kwa Mai Mai is the wedding kist, which is still very popular among migrants returning home for a visit or among mineworkers whose contracts have expired. For many years, returning migrants would not dream of going home without a wooden kist—lavishly decorated with mirrors on the lid and/or the sides and with an African motif worked artistically into the surface of the wood in the form of a wood cut or through a burning process.

Kwa Mai Mai has also long been a convenient location for an interesting cross-section of self-employed village migrants, such as skin/hide workers, carpenters, snuff producers, sjambok and spear makers, and bangle makers. The bangle makers are very skilled at intricate designs, which are often applied to beautifully crafted, ornamental ‘dancing sticks’ and purses. The compound is also home to healers and several well-known herbalists, whose shops are veritable cornucopias of remedies comprising herbs, animal extracts, snake skins and dried snake venom. Traditional medicine is a major industry today; and some shops are very large indeed.

There is a high demand for traditional regalia and assorted ornaments among the mineworker dance teams: weekend entertainment is popular at the mines and has translated into a thriving trade for those skilled in producing cultural goods. If it so happens that customers do not visit the compound, craftsmen sometimes travel across the reef, laden with goods they have made, visiting one mine compound after another.

Of course, villagers are known for their ability to travel long distances on foot, travelling from one village to the next or even across different izigodi (wards). With the discovery of diamonds and gold during the middle and latter part of the 19th century, Africans used to practically walk the length and breadth of the country to join the labour force. It was not uncommon, for example, for job seekers to walk for a week or more, or even a month, to get to Kimberley or Johannesburg, the country’s diamond and gold mining hubs. On these long journeys, they wore handmade sandals known as izimbadada or izingxabulela, which have become ubiquitous and are highly sought after from the skilled craftsmen at Kwa Mai Mai.

The sandals are multi-purpose footwear, used mainly by Zulus, who wear them both during their traditional dance routines and for their day-to-day movements in and around the city. Though simple in design, they are particularly sturdy and have withstood competition from many other (including foreign) footwear designs, even coexisting with leather sandals and flip flops, which were unknown to Africans. Today, these sandals are popular among various traditional dance groups, such as those who dance umzansi from Bergville, ushiyamen from the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands and isibhaca from the south coast of KwaZulu-Natal, and those from Nongoma, the heartland of the Zulu Kingdom.

The snuff makers import a wide variety of very crude and harsh tobacco from the Transkei and mix it with aloes and other vegetable matter, after which they dry it and pound it into fine powder using a large mortar and pestle. In this way, they make sure that inveterate smokers get their fix. Among others, izinyanga (traditional doctors) and izangoma (diviners) use snuff, which has always been regarded as the conduit to the ancestors when the living wish to appeal to the departed for the well-being of the earth. Using snuff and burning incense are prerequisites if the ritual of communicating with the departed is to deliver the intended results.

~~~

- Dr Sipho Sithole is a Research Fellow at the Johannesburg Institute for Advanced Study and holds a PhD in Anthropology from Wits University. Sithole’s research interests are marginality and belonging, language and identity, music and society, culture and celebration, migration and integration, postcoloniality and re-imagining, as well as the creative economy.

~~~

Publisher information

This book will let the reader into the world of migrant workers and how they have used their culture and heritage to reimagine and create a new socioeconomic order through the production of cultural goods and services.

This is the story of Kwa Mai Mai; an economic trade zone that has captured the imagination of people who dared to dream. Kwa Mai Mai is the beginning of everything Johannesburg is meant to be, the City of Gold, a place where dreams deferred become true.

The book tells a story of a people’s culture, wrapped in beautiful memories of life in villages left behind but collectively remembered by those who refuse to forget, lest they lose themselves in the concrete jungle that knows no mercy.

This is a story of how cultural memory, sacredly preserved and transported to new geographies, can serve both as cultural weapon that can be used to resist subjugation, while unleashing it as an economic weapon to turn those priceless traditions into tradeable commodities. The book narrates a story of how those who are the keepers of cultural memory can wield it as a weapon of survival and use its power to petition the entrepreneurial and creative spirits buried deep down in the souls of their true being.

The book raises an argument built on an assumption that if cultural memory can be stored and retrieved through artefacts, sites, ceremonies, myths and rituals, including texts, then Kwa Mai Mai assembles and converges these into one place and space of worship and celebration.

This is a place where the hypervisibility of its bearers is always in a constant fight against being eclipsed by those who would rather pretend it did not exist—the City that created it.

The book combines both the author’s observation and interpretation gathered from ethnographic work of over four years, as well as the voices of those who reluctantly remained in this city when no other alternative presented itself, short of returning to the villages in absolute defeat.