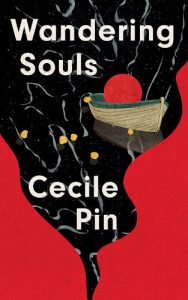

The JRB presents an excerpt from Cecile Pin’s debut novel Wandering Souls, longlisted for the 2023 Women’s Prize for Fiction.

Wandering Souls

Cecile Pin

HarperCollins Publishers, 2023

1

November 1978—Vung Tham, Vietnam

There are the goodbyes and then the fishing out of the bodies—everything in between is speculation.

In the years to come, Thi Anh would let the harrowing memories of the boat and the camp trickle out of her until they were nothing but a whisper. But she would hold on to that last evening with all her might, from the smell of the steaming rice in the kitchen to the touch of her mother’s skin as she embraced her for the last time.

Her mother, she would remember, preparing her daughter’s favourite dish, caramelised braised pork and eggs, while humming ‘Tous Les Garçons et Les Filles’ by Françoise Hardy. The French had left Vietnam twenty-five years prior, but their music still lingered, the yé-yé melodies filling the homes of the village of Vung Tham.

Anh was packing her rucksack in the bedroom next door, debating what to take and what to leave behind. ‘Pack lightly,’ her father had told her. ‘There won’t be much room on the boat.’ She held her school uniform to her chest, pleated skirt and white shirt whose sleeves were too short for her sixteen-year-old arms, and placed it in her bag.

Her brothers Thanh and Minh were doing the same in the bedroom across from hers, their belongings scattered over the tiled floor, and she could hear them arguing. They had to share a rucksack between them, and Thanh maintained that because his clothes were slightly smaller, as he was ten and Minh was thirteen, Minh should pack fewer items than him. ‘Your clothes take up too much space. It’s only fair if I pack more than you.’ Their mother went to the room to investigate the noise, the smell of the caramelised pork following her. As Thanh began to explain the problem to her, his voice faded, her exasperated face quieting his trivial concern. ‘Sorry,’ he muttered, as Minh looked at him with a triumphant smile. ‘It doesn’t matter.’

Through her open door Anh saw their younger brother Dao watching the quarrel unfold from the edge of his futon. He fiddled with his blanket anxiously, his blue T-shirt too big for him, a hand-me-down from Thanh. He didn’t like his brothers arguing, Anh knew, anxious over having to pick a side and vexing one or the other. Out of all her siblings, Anh worried about Dao the most. She worried about life for him in America, that his shyness would make it hard for him to make friends once there. She had spent the past few months trying to break open his shell, encouraging him to play Đánh bi or Đánh đáo with the other children of the village by the banyan tree. ‘No, please,’ he would say, half hiding behind her. ‘I’d rather stay with you.’ Their mum pulled him up from his bed, his hands outstretched and holding on to hers. ‘Come on, Dao,’ she said as she picked him up. ‘Your brothers need to finish packing.’ Together they left the brothers’ bedroom and as they passed Anh, Mum asked, ‘Are you done? I could use your help with dinner.’

‘Yes, Ma,’ Anh said, stuffing her rucksack with the remaining pieces of clothing spread out on her bed. As she followed them into the adjacent kitchen, her mother released Dao from her arms. ‘Can I help too?’ he asked. Their mother gently brushed the hair off his face and said, ‘No, there’s no tasks for little boys tonight. You can go in the living room with your father.’ He nodded, disappointed, and after glancing at Anh with his round eyes he went to the living room. Anh suspected that her mother had wanted a moment alone with her in the kitchen, to treasure an instant with her eldest daughter before her leaving.

Her baby brother Hoang was asleep in his cot, lulled by the rhythmic sounds of his mother’s cooking, clinking pans and simmering oils. Anh stirred the pork as her mother chopped the fermented cabbage into small chunks, a tremble in her hand. It was as if they were acting a scene; a normal mid-week evening, the kitchen their stage and the pots and pans their props. But as the two of them moved around the small space they avoided one another’s gaze, their usual chatter reduced to the occasional instruction: ‘Make sure you get the scraps at the bottom of the pan’ and ‘Add a bit of nước chấm’. Several times Anh saw her mother opening her lips as if to speak, as if to let out a thought that had been weighing on her, but only sighs would come out.

Her younger sisters Mai and Van were setting the table, carefully juggling stacks of bowls and plates in their small hands, their long hair flowing behind them, the tap of their bare feet scarcely audible. While doing so they revised their school lessons of the day. ‘Four times four, sixteen; four times five, twenty; four times six, twenty-four,’ they recited in a singalong voice, one of them making the occasional mistake, the other one telling her off for it. ‘Twenty-eight, not twenty-six,’ Van said to Mai as they made their way back to the kitchen. Anh plated up the pork, steam rising from the pan, and handed them each a dish. They liked bringing the food to the table because they could snatch a few bits along the way, crumbs on their white vests giving them away. Sure enough, once they were out of sight, Anh heard Mai say, ‘That’s too big a piece,’ while Van shushed her.

At the back of the living room, her father sat by the home altar, his back crouched, while Dao watched him attentively from the worn-out leather sofa. The altar was adorned with framed photos of their grandparents. There was Ông nội and Bà nội, standing in front of their house and looking sternly at the camera, a newborn Van in their arms. In the background was their neighbour’s chicken, roaming on Vung Tham’s dry and dark soil, their laundry hanging between their kitchen window and the nearby palm tree. There was Bà ngoại, posing by an ornate staircase at her daughter’s wedding, small heels on her feet and her hair in a bun. And there was Ông ngoại, looking like an old Hollywood star in his close-up portrait, his white teeth showing and his hair barely grey. The four of them had died successively in the last three years, after Saigon had fallen and the last soldiers had gone back to America, like a gust of wind rippling through waning leaves. By then they were old and weary, and their deaths hadn’t come as a surprise. But the rapid pace made Anh wonder if the war had had something to do with it, if hope could be a source of life and its vanishing a harbinger of death.

With the back of his sleeve, Anh’s father wiped the dust off the portrait of his mother, inspecting the frame by the candlelight. Once he was satisfied with its cleanness, he put it down carefully next to the others and lit up some incense. He held the burning stick in his hands as he prayed, and soon her mother emerged from the kitchen to join him. She struck a match and lit the incense with it, and as they prayed together Anh heard them murmuring her name alongside those of Thanh and Minh, pleading for safe travels and calm seas. Dao stood up from the sofa and approached them, pulling on his mother’s shirt. ‘Can I have one too?’ he asked, and she handed him her incense stick, lighting another one for herself. Anh watched as his timid voice joined his parents’ prayers, the three of them on their knees, their ancestors watching over them. After a few minutes her father stood up, clasping his hands. ‘Time for dinner,’ he said.

~~~

- Cecile Pin grew up in Paris and New York City. She moved to London at eighteen to study philosophy at University College London and received an MA at King’s College London. She writes for Bad Form Review, was longlisted for their Young Writers’ Prize, and is a 2021 London Writers Award winner. Wandering Souls is her first novel.

~~~

Publisher information

‘A deeply humane and genre-defying work of love and uncompromising hope.’—Ocean Vuong

An extraordinary story of the journey of one young family through love, loss and unwavering hope.

There are the goodbyes and then the fishing out of the bodies—everything in between is speculation.

One night, not long after the last American troops leave Vietnam, siblings Anh, Thanh and Minh flee their village and embark on a perilous boat journey to Hong Kong. Their parents and four younger siblings make the crossing in another vessel but as weeks go by it becomes clear that only one party has survived the voyage.

Anh, Thanh and Minh suddenly find themselves alone in the world, without family or home. They travel on, navigating refugee camps and resettlement centres until, by a twist of fate, they arrive in Thatcher’s Britain. Here they must somehow build new lives with only each other to turn to, but will that be enough in a place that doesn’t seem to want them?

In this piercing debut, the siblings’ faltering journey is deftly interwoven with the voice of their lost younger brother, Dao, following them from a place between the living and the dead, and the records of an unknown researcher intent on gathering the strands of their story.

Wandering Souls paints a heart-wrenching portrait of a family in crisis while exploring the healing power of stories.