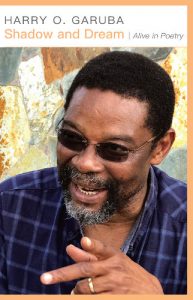

The JRB presents Sanya Osha’s Foreword to the new reissue of the late Harry Garuba’s poetry collection, Shadow and Dream.

Francis Nyamnjoh (Dept of Anthropology, University of Cape Town) and African Studies scholar Ahmet Sait Akcay, a former student of Garuba’s, have been the main drivers behind the reissue.

Shadow and Dream: Alive in Poetry

Harry O Garuba

Langaa RPCIG, 2023

Harry Garuba: A Priest at Christopher Okigbo’s Shrine

Harry Garuba arrived on the Nigerian poetry circuit as a fully formed poet even though he was a young man in his early twenties. He was immediately received as not only a prince of poets but also a man of the people on account of his untiring gregariousness, effortless charm and almost heartbreaking tenderness. Harry adored beauty, and most especially, poetic beauty. He was born a poet. He didn’t even have to write poetry. Remarkably, he managed to fill the seemingly barren moments of his life with poetry and its varied cadences. His looks, smile and composure radiated poetry and the intimacy of gentle and perpetual communion. He embarked on a quest by standing still but his stillness was not informed by stasis or regression. Instead it seemed to be buoyed by the energetic movement of deep waters beneath the surface of a river. Harry’s apparently simple poetry masked easily overlooked layers of meaning, pathos and ellipsis.

The flow of his poetry mirrored the natural patterns of his speech and the manner in which his soul moved and revealed itself as calibrated sequences of creative grace. He was exceptionally courageous in offering up his inner truths and vulnerabilities. He broke down hardened defences with his generosity and naiveté. Indeed his poetry was an integral part of his carefully moulded world, and his world was nurtured through a warm, fuzzy glow that was similar to the air that gave luxuriant leaves even more colour, density and radiance.

Harry did not find his voice totally independent of illustrious forebears. He was an acolyte of the great Christopher Okigbo. He never grew weary of reciting lines from the visionary poet’s oeuvre or finding new ways by which to celebrate and immortalise him. Okigbo was the undisputed patron-saint of the poets based at the University of Ibadan (UI), Nigeria, where Harry had studied and worked. They sang and rhapsodised at Okigbo’s altar, they drank wine at his fount and inhaled the mists that emanated from the face of the immortal poet’s moon. Indeed Okigbo was akin to a deity whose name was not mentioned recklessly or in vain. Harry never baulked at teaching his own significant gathering of admirers how to honour and revere Okigbo. He was first and foremost a high priest in the hallowed shrine of the inestimable poet.

Along with a few friends, Harry established the Poetry Club at UI Ibadan in the early nineteen-eighties, and Okigbo Night was the highlight of the academic calendar, in which poetry competitions, readings and reflections were held to commemorate the slain poet, who was killed during the Nigerian Civil War in 1967.

Indeed Okigbo was not only a poet’s poet but also an incorrigible man of action. And so nothing could prevent him from playing a role-which turned out to be fatal—in the horrendous war. Okigbo’s unchallenged lyricism is expansive, celestial and borderless. In his unique existential trajectory, the supreme lyrical poet embraced unequivocally, the fate of a star-crossed man of war with utterly devastating consequences.

Harry, on the other hand, committed to the art of lyricism and the unalloyed purity of the supreme poetic vision. Indeed he was a lyrical poet blessed with a lyrical spirit and the thought of wreaking unwarranted violence upon anyone or anything was difficult for him to conceive. The realm of politics was also not meant for him as an active participant. He preferred to eschew the cloak and dagger realities of politics and chose to pursue Okigbo’s original idea of aestheticism to its ultimate resolution which was to locate, isolate and refine the essence of poetic beauty in extremis.

Such a radical conception of the art of poetry was cultivated and nurtured in the poets who converged around Harry at Ibadan. He demonstrated that in life, poetry could also be the defining philosophy of both consciousness and action. If one was not a poet and couldn’t compose acceptable lines, one could, at least, will oneself into being a poet by assuming the ways and consciousness of a bard. One simply declares, ‘I live poetry with beauty and equanimity in my soul, thoughts and deeds. I illuminate ether with my inner light, I bless every company that encounters me with my charisma. I sing the songs that my ears have never heard but emanate directly out of you. I disregard my physical limits and confinement in order to become you.’ What could be greater poetry than that? This was a central credo of Harry’s life.

Harry formed his uniquely tender poetic sensibility based on affect, the ethics of friendship and communion. This lyrical sensibility was evident at the very beginning and stayed with him throughout his life. It was also a sensibility much given to the beatific virtues of song, verdant nature and the unblemished human subject. Arguably, this is a vision that might have been fashioned even before he encountered Okigbo and may have been integral to who he was as a human being.

There was also a sly element of dusky and slightly mysterious melancholia in Harry’s outlook that encompassed Pablo Neruda, Cesar Vallejo, Octavio Paz, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Mario Vargas Llosa, Manuel Puig, and all the other great poetic souls (who were some of Harry’s favourite authors)—even when they were ostensibly prose stylists—of South America. The grotesque sense of the macabre that convulsed and terrorised Latin America was similar to the tragicomic visitations of gargantuan proportions that erupted frequently in Africa. If Latin America could come up with magic realism, Africa on its part, had a more original version, animist realism, with the likes of DO Fagunwa, Amos Tutuola, Sony Labou Tansi and Ben Okri providing us with scenarios and characters that continue to haunt us in our dreams.

Agreeing with a visiting American scholar who called Ibadan poets ‘tortured souls’, Harry milked this ingenious moniker for all it was worth. He demonstrated that there can be a shroud of tranquillity in the manner in which distress and agony could be confronted. He showed that melancholia and unrequited love could be significant ingredients for composing timeless poetry. And when he offered a smirk in the face of life-crushing tragedy, he was only affirming the verities of immutable bitter-sweet realities. Indeed the aftertaste of sublimation bears a taint of melancholy. After a period of light and grace, there was also the inevitable descent into gloom.

Harry was a child of the Niger Delta. He understood the hidden music of its deep brown rivers and creeks. He recognised the voices of the birds that sang across dark, lush vegetation and forests. And just like the other great Nigerian poet of the delta, John Pepper Clark-Bekederemo, he understood the elemental force of nature’s poetry.

Harry’s Shadow and Dream and Other Poems represents his first completely realised song about a poet’s awakening at dawn. Naked in front of his baptismal waters, his reflection is pure, uncluttered and utterly inviting. He is inviting the world to drink out of the purity and generosity of his spirit, to bask in the muted illumination of unadulterated youth. He is calling on his audience to follow his reverie with the hope, courage and loyalty of first time initiates. Harry is both an initiate and a high priest tenderly making his way through frail ferns and thick grasses and the entire gamut of human emotions and consciousness to a horizon of recognition and acceptance. The fortunate denouement of this quasi-mythical-cum-poetic journey, is that Harry, leading his band of trusting followers, reaches his destination with all the poetry of his soul and the tenderness of his vision still very much intact.The importance of this slim collection of verse can be perceived in the totemic status it maintains among the so-called ‘third generation of Nigerian writers’, most especially those engaged in poetry. In contrast to Okigbo’s landmark Labyrinths, which is an epic of grand quests both personal and collective, Shadow and Dream and Other Poems is a nuanced song of poetic efflorescence, a eulogy for youthful experience, élan and emotional adventure. But much of its subtle power stems from its measured understatedness. Devoid of the customary braggadocio of youth, it is a guarded celebration of affect, tenderness and wholesome feelings. Ultimately, its subtlety, equanimous undertones and delicate but unfailing charm, lent a profound sense of poetic liberation to an entire generation of poets.

Sanya Osha,

Cape Town, September, 2022

~~~

- Sanya Osha, an author of several books, works at the Institute for Humanities in Africa (HUMA), University of Cape Town.

~~~

Publisher information

‘I try to think what Harry would have thought when I face difficult local/global questions. He is alive in my work.’—Professor Gayatri C Spivak, Department of English and Comparative Literature, Columbia University

Harry Garuba’s Shadow and Dream, a slim yet highly influential collection which immediately gained a cult following, has continued to elicit the awe of poets and lovers of literature within the Nigerian literary scene.

First published in 1982 when Garuba was still in his early twenties, it demonstrates an uncommon maturity, vision and understated confidence that have rarely been encountered ever since its initial release.

With the publication of this edition together with a new Foreword and Introduction, Garuba’s landmark work moves from cult status to canonical validation.