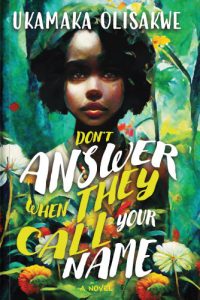

The JRB presents an excerpt from Don’t Answer When They Call Your Name, the new novel from Ukamaka Olisakwe.

Don’t Answer When They Call Your Name

Ukamaka Olisakwe

Masobe Books, 2023

Prologue

Mbido

Our story begins on a farm.

It was the year of the white yam, and Big Father was pleased with his harvest. Mother was not.

Big Father was a man of great height and resolve. A dedicated farmer, he had broken the hard soil and ridged the land. He planted his yams and when they had germinated, their tendrils creeping towards sunlight and tangling with each other, he drove stakes into the soil and watched as the plants curled around them, reaching for the sky; the healthiest yam farm in the whole of the universe, one that stretched from one end of the world to the other.

The yams flourished. The roots gobbled up the manure fed to them and they spread their hands, the tendrils thick and fat—the width of a baby’s hand. Weeds sprang from the earth and tried to suffocate the yam plants, and Big Father pulled every one of the weeds out and dumped them in a pile to whither. After he was done, after he irrigated the land and fed it cow dung and dead things—organic fertilisers that nourished his precious crops; after the yams grew without impediments, birthing tubers as fat as toddlers, he stood back and breathed, pleased with the work of his hand.

Big Father had a wife—Mother—who was eager to help, and who wanted to join in the farming of the yams, for she came from a race of industrious and ambitious women whose stories travelled the universe. But Big Father rejected her help. He gave her a small piece of land far from his yam farm, and said she must only cultivate female crops, like cassava and cocoyam; what mothers before her had done, and which to him were suitable for a woman.

Mother was furious. The first child of her parents, she had worked her father’s yam farm and made profits from selling the rich crop. Her father did not mind that she preferred to work on the land; he did not mind that she kept the profits she made after trading her harvest at the Universe Market; he did not mind that she did what sons were meant to do, because she was his only daughter and he would bend some rules to make her happy. He had initially insisted she work with her mother on the female farm, but Mother was a stubborn, cocky sort of child who did what she wanted. Her great-great-grandmother was Ifejioku, the mighty deity responsible for yams in their world, and to whom farmers prayed before and after they harvested the noble crop. But over time, men took over the responsibility of farming the crop, appropriated it, declared it ‘the male crop,’ because it had become a household staple and because they had gotten fat off the wealth they made from it. They dedicated their sons to the service of the crop and called themselves ‘Njoku,’ rising to the position of nobility in their communities.

Mother fought against this, insisted she must farm the crop. Her father tolerated this until she saw her first blood, then he quickly plucked her from her farm, audited all she had amassed for herself, and divided them among her brothers.

‘But, Papa,’ she protested.

He shut her up with a raise of his hand and reminded her that a girl would always leave her father’s house and move into her husband’s, where she would start her own family and raise children; where she could do as she pleased and manage her own affairs. Mother did not care about marriage or children, but the idea of doing as she pleased in her own home appealed to her, and so she obediently agreed to marry Big Father.

She danced energetically on her wine-carrying day. She smiled into the faces of her brothers, who had bought for themselves the rarest jewels and the finest silks from the proceeds of her hard work.

‘Watch me flourish,’ she told them as she left their world and moved in with Big Father on his vast farmland.

The sight of the blooming yams welcomed her—their rich green leaves, the properly manured ridges, the irrigation paths Big Father had crafted. She stood on that land, on the first day of her new life, and something lifted in her chest.

‘This will do,’ she muttered, then tilted her face to the sky, where she sensed that her brothers were watching. ‘Watch me flourish,’ she said again.

#

Her marriage began to disintegrate in less than a year.

Mother stood on Big Father’s farm and hissed at the rich crop taunting her with their fat, healthy green tendrils. She was nineteen years old and she didn’t want a child yet. She wanted to become a successful yam farmer and trader, just like the mothers before her who were famous for their exploits at the Universe Market. Getting Big Father to give her some seedlings or even allow her to venture into yam farming had become a major problem. And yet, despite her desperation, Mother would not beg; she was beautiful and arrogant and stubborn, and she tended to sulk. Her father would scramble to indulge her, to get her to smile for him; not her husband. Big Father did not bother to ask why she sulked, why she hissed when he walked past, why she would not share his bed, why months passed and she refused to farm female crops.

A neighbour noticed the rivalry between husband and wife and offered to hear their grievances, to make peace between them. But Big Father did not care at all; he would come home from the Universe Market and sit in the middle of their compound and spread out bags of jewels, his returns from the sale of his yams. That haughty display of wealth was hard to miss, making Mother angrier. When it became clear that he would never approach her to make peace, that her emotional fits would not break down the walls he built around his heart, she stopped sulking.

Mother was stubborn and arrogant all right, but she also had a good head on her shoulders. She knew that to get what she wanted, she would have to find a way to break down Big Father’s walls, to make small compromises so that she would be happy in his house, so that she would regain all she had lost to her brothers on account of marriage. She waited until the harvest season was over and harmattan had come and gone, and the rain had poured and prepared the earth for farming again, before she went to Big Father with a great plan.

There were many stories about Big Father depending on who you asked: some said his mother, The First Mother, suffered many stillbirths and so the creator, Onye Okike, built new bodies until they found the one who gave them children; that The First Mother finally gave birth to Big Father after a lifetime of trying; that the creator gave Big Father a farmland, which was this world, on the runt of the universe, to cultivate chosen crops and populate the earth; and Big Father worked it so assiduously, broke the hard soil and made much profit, more than all the other children; that he acquired more worlds from his siblings that stretched from one end of the galaxy to the other; that the humongous size of his estate was why everyone began to call him Big Father; and that he was a ruthless man who guarded his acquisitions jealously and was merciless towards anyone who trespassed on his property; that his mother was buried in this world, not on the hallowed grounds where Onye Okike and the first mothers rested; and so he loved this world like a child would their living mother. The stories about him were numerous, but they all agreed on one thing: Big Father would never budge on matters concerning his yam farm. And this was why he did not care for his wife’s petulance.

But Mother was undaunted by the stories. She had set a goal for herself, and with that, she went to Big Father’s quarters, at the front of their vast compound, bordered from hers by a short ogirisi fence. The distance between their quarters was a day’s journey. The dust whorled that morning as she set out, sweeping red upa into the air, tinting everything brown-red. Coconut trees flanked the entrance of his quarters, and birds pecked away at the overripe bananas dangling from the squat trees on either side of the compound.

She knocked on Big Father’s door and waited. She should not have had to, but she had been angry with him for a long time, and it had been months since she shared his bed. So she felt like a stranger again, just like she had felt that day, one year before, when he came to their house to ask her father for her hand in marriage. It took a moment, and then she heard the shuffle of his feet, the heavy thud of his steps as he approached the door, and then he stuck his head out first, his brows meeting at the middle in a quick frown before a teasing smile spread over his fine face.

‘This one you have decided to show up at my door, I hope everything is fine o,’ he said, clearly resisting the urge to laugh.

She clenched her teeth and clasped her hands behind her back; she wanted to punch his face. ‘I am well, my husband,’ she told him. ‘I have an important matter I must discuss with you.’

He laughed again, leaned against his door frame and folded his arms. ‘Ehen? What is this important thing that finally dragged you out of your hut to my quarters at this time of day?’ He looked at the setting sun, the orange glow washing into his yard. He raised a brow in mischief, stared at her hard. ‘Have you finally decided to return to my bed?’

‘Yes,’ she blurted, out of breath.

‘To give me children?’

‘On the condition that you will let me farm yam crops.’

He straightened up, dark clouds rising in his eyes. ‘You can only farm female crops.’

‘Listen, you are no longer a young man,’ she said. ‘You have to start thinking of the children who will take care of this place when you can no longer do everything by yourself.’

Her submission caused him to laugh, a loud cackle that shook the very ground she stood on. ‘Look,’ he said, ‘when I am desperate for sons who will take over from me, I won’t have to beg you. I can easily find women who will be willing to do what I want.’

‘Good luck finding anyone as resilient as me. Do you know the mothers I come from?’

‘Your great-great-grandmother is Ifejioku. We already know that.’

‘Yes! And we do not bend for anyone. We never succumb, no matter what. This is what you should want in your children. Children who would stubbornly defend your territories from those vultures you call brothers, who are waiting for you to keel over so they can take over your properties.’

Big Father reddened in the face. ‘No one would dare!’

‘You have no idea how jealous people are of your wealth.’

He breathed hard, his nostrils flaring. ‘You will not put ideas into my head, do you hear me?’

And she stood her ground, lifted herself to the tip of her toes so that she matched his height, so that she met the fire in his eyes with her rage. ‘Your mother did not give up—’

‘Don’t you dare talk about my mother.’

‘I never ever give up. Isn’t that what you would want in your children, a race that never ever succumbs, no matter the challenge life throws at them?’

Her words got to him; the mention of his mother always got to him. He turned abruptly and returned to his hut, his words carrying out from the dim room before he slammed his door shut. ‘Go home. I have to think.’

She waited for his response. She waited for days, then weeks. And just when she thought she might have to pay him another visit, he showed up on her front yard one early morning, breathing as though he had raced the entire distance to catch her just as she stepped outside to wash her face.

‘Four sons,’ he said. ‘You will give me four sons. Then you can have whatever you want and do whatever you feel.’

‘Four sons,’ she said, nodding her assent. ‘I will come to you when my body is ready for your children.’ And with that, she returned to her room. She held her joy tightly inside, tried not to sing out loud, until she was sure he had left, until she was alone again. And then she lifted her voice in a melodious song that carried out into the universe. Her music trilled for days.

#

Mother knew the best time to conceive sons; mothers who came before her had taught their daughters. They counted days after their periods, they knew the best time to get a boy, when to hold a girl. They could tell the sex of the baby from the feel of their breasts, the severity of their morning sickness. Mother felt all these, and when the time came, her first son, Eke, slipped into the world with a lusty cry.

‘Here,’ she told Big Father, who wrapped the baby in a soft ogodo. ‘You have your first son. Three more to go.’

‘You have done well,’ said Big Father. ‘You will have everything you ask for when you have given me four sons. I am a man of my word’—he smiled—’I always keep my promises.’

Mother got pregnant again within two months; she wanted to hurry through the process. Her body broke and swelled; her skin felt like a strange cloth she was trapped in, and she no longer knew how to wear it. Her yard was filled with the cries of her always-hungry son, Oye, and her nights were short. But then guests started pouring in from the worlds, bearing gifts of rubies and gold and diamonds and oils and scents. She welcomed them with smiles. She showed them her baby. She swayed in dance when they sang ceremonial songs for her. She drank the hot soups her mother prepared and took her sitz bath religiously. She told everyone that she was fine, but when she retreated into her room and closed her door, she slumped on her bed in fatigued grief.

Still, she brought her husband two more sons—Afo and Nkwo. The last boy came at dawn, when the moon was closing its eyes in sleep and the sky hung like thick grey hills. Big Father lifted his boy, smiled up at the bawling face, and said, ‘You have done well, my wife. He is beautiful and perfect.’

She sat up and cleaned herself. She put away her birthing clothes and washed and oiled her body with udeaki. She lined her eyes with otanjele. She scented her body with oils. After she had adorned herself as she remembered she used to be, even though a lot had changed in her appearance—her breasts were fuller, her hips wider, and her periods were heavier—she still had her mind set on her goals. She went to Big Father and asked for yam seedlings and an extra portion of land. Harmattan had come and gone, and the rains had fallen and prepared the soil for farming.

Big Father leaned against his door frame and squinted at her. ‘Our sons are still too young. Who is going to take care of them when you go to the farm?’

She took calming breaths; she would not let her rage overtake her cool demeanour. ‘We will employ good nannies,’ she said.

‘Nannies? To raise my children? To teach them whose values? No way.’

‘We had an agreement,’ she reminded him.

‘And I have not changed my mind. All I ask is for you to stay at home a little while, until our babies are strong on their feet, then you can have your yams and farm any portion of land you choose.’

He retreated into his hut, and before he would slam the door shut in her face again, she noticed something different in his mien—the smirk on his face, a proud set in his shoulders, and the steel in his eyes.

#

On the week of their son Nkwo’s tenth birthday, Mother came to a realisation about Big Father. He would never let her farm yams: he would never allow her to have what she truly wanted; he would keep making demands, stretching the years, until she had grown old, until motherhood had wrung her out.

Big Father threw the boy the best party in the universe, drawing people from far and wide to jolly with him. He employed the best caterers. He slaughtered the fattest cows. The grown-ups partied on the eve of Nkwo’s birthday until the following afternoon; they sang and drank and ate and danced. When they had exhausted themselves, their children took over in the afternoon, music booming out from the compound into the universe. Everyone noticed; everyone stopped by to pay their homage, for Nkwo was Big Father’s favourite and would later have the biggest market day dedicated to his name.

Mother watched all this from the corner of her eyes, offering bright smiles whenever people hailed her. She danced when they sang for her. She laughed when they called her a ‘strong, great woman.’ She carried her rage inside, bound it tightly against her body with her fine ogodo—the rarest akwete wrapper, a gift from her mother on her wedding day. She did not talk to her husband or go to him when he waved her over to come and dance with him during the jewel-spraying time. She watched him with their son, her body swelling with bile as they danced in circles, as the guests sprayed them with the finest and rarest jewels mined from exploded stars.

The following day, after the guests had packed up and returned to their worlds, and she had cleaned her yard and fed her children, she went to Big Father’s quarters, tightened her hands into fists, and brought them down on his door. She banged with all her might, and only stood back when she heard his angry voice from inside.

‘Who the hell is pounding on my door like that? Have you gone mad?’ And when he threw open the door and saw her, he sighed and hissed. In his hand he gripped a famous machete, lights shooting over its glinting surface, the same electricity that had climbed into his eyes. ‘Have you lost your mind?’ he asked her.

‘You never planned to keep your end of our bargain, did you?’ she said.

He put the machete away, and his eyes returned to normal, dull and human. ‘You must wait until my sons have grown into men—’

‘Your sons,’ she said, and smiled a sad smile.

Her words perhaps stung him, because he inched closer, and when he spoke again, his tone was grave. ‘You must wait until they are old enough to take wives, then you can go ahead and have whatever you want. That’s what a good mother is supposed to do.’

Her eyebrows shot up, veins popping on each side of her temples. She had expected him to deny the accusation, or even find a way to soften the blow, to consider her feelings despite everything. But his bluntness cut deep. He might as well have spat in her face. She wondered if he was really that heartless, that selfish; the vilest person , to whom she had given the best years of her youth.

She should say something angry in response. She should throw a fit, hit him, or worse, grab the machete and take a swing at him. But she only smiled and nodded. ‘I have heard you, my husband,’ she said, even though her mind was going in circles, roiling with thoughts, webbed with rage, seeking the best and perfect way to get back at him, this man who stole her best years and tricked her into bringing him children when her mind was not ready to take on the responsibility of motherhood, when she wasn’t even sure that she wanted to be a mother. ‘I will wait until our sons have become men, then I will farm the yams,’ she told him sweetly and went back to her hut.

#

It took two nights of thinking, two nights of her staring at the ceiling, listening to the sounds of night outside her window, playing scenarios over and over in an endless loop in her mind, reaching deep inside her to imagine what the mothers before would do in such a situation, what they would do to a man who snatched their youth and condemned them to an unhappy marriage. And then she arrived at a solution that she was sure would ring for the ages in the entire universe.

The following day, she waited until the sun had risen to the base of the trees in the east, when she was sure that Big Father would have left for the Universe Market, before she took her sons to her own hut and locked them inside. Then she marched to Big Father’s farm, stood in the middle of the vast land and looked at the sky. That afternoon, the clouds were a brilliant white, and the sun shone with a burning passion. She closed her eyes and summoned in her mind the map of the universe, whose paths she had learned when she was only a child. She listened, her mind tracing the orbits of other worlds, the position of the stars, the direction of the moon, the glory of the sun, and finally, the floating asteroids tumbling endlessly in the vast space. She tracked their dimensions with her mind, seeking the perfect one whose targeted fall should obliterate the farm without dragging its devastation to her doorstep.

It took a moment, before she sensed it, the debris from a dead star, buzzing past. She stilled her mind and reached deep inside where her rage sat boiling. Taking a deep breath, she stretched out her arms, arched them to the point where the asteroid floated, and let out a sharp cry, a sonic burst that pierced through the sky, bounced into space, and pulled the asteroid towards their world.

Her pores burst open. Her nose flared. Her chest heaved. The clouds groaned, darkened, blocking out the sun. The wind whorled, and birds flittered from the trees, flapping and flapping, winging out of the path of the catastrophe. She did not open her eyes as she pulled, as she dragged destruction to her husband’s precious farm, where he buried his mother; these grounds he worshipped and elevated and loved more than life itself.

The asteroid hurtled towards earth, carrying fire in its tail.

She moved away from its path just in time. And when it hit, the force lifted her into the air and rammed her back to the earth, knocking the strength out of her. Then the force rippled in waves, in a wide circle, obliterating everything in its wake. The thunder of its destruction reverberated throughout the universe.

Mother lay on the ground, drained. Dust covered everything. Her ears were ringing. The earth was still shuddering. She heard her sons’ cries. She heard the discordant voices of people arriving with rescue vehicles. She sat up slowly, looked around her, and saw that she was in a cavernous valley the asteroid had excavated. And the yams were gone, their leaves and tendrils now charred corpses smoking in black death.

She was thinking, where were her sons? Were they okay?—when she saw Big Father descending into the valley, his footsteps heavy, sad, angry—emotions that slowed his gait and hunched his shoulders. He gripped his machete tightly in one hand.

‘What have you done?’ His voice rang with defeat, the tone of one whose world was done, all hopes dashed; she had reached into his throat and ripped out that which he cared for most, above all things.

She looked at him and felt a smidgen of pity for him, this stubborn man who had sealed his ears against her plight, mocked her with his success, and pushed her to the wall, until she was forced to throw all fists at him, anything at all, to hurt him just as he had done her. The lights in his eyes shone so bright, they glistened with the tears that rolled down his cheeks. They rippled across his skin and turned his complexion into lightning, his voice clapping like thunder.

‘What have you done to my mother’s grave?’ he asked again.

She should be worried. She should be filled with remorse. She should get off her bottom and talk to him. She should do all those things women were expected to do to quell their husband’s anger. But then she remembered the mockery, the taunting, his satisfaction in her misery.

‘Now you don’t have yams and I don’t have yams. No one has yams. So, we are even, aren’t we?’ She began to laugh. She had wanted to cry. She wanted to wail about how her life had turned out, how her marriage had finally disintegrated into tatters; to wail that she regretted what she had done but would do it again if she could. But when she tried to cry, all that spilled out of her was laughter—searing, mocking laughter.

‘We are even now, aren’t we?’

She laughed and laughed.

She was still laughing when she saw it—the swing of his machete. It happened in a flash. He did not allow her a second to catch her breath. She only gulped as the blade rushed towards her head. Then a quick slash. Pain exploded in her eyes. A scream split from her throat. The world turned black. And she was falling into a deep, dank void.

~~~

- Ukamaka Olisakwe grew up in Nigeria and now lives in the United States. A UNESCO Africa39 honoree, a University of Iowa IWP fellow, a VCFA Emerging Writer Scholarship winner, a Miles Morland Foundation Scholarship finalist, and a Gerald Kraak Prize runner-up, her works have appeared in the New York Times, Granta, Guernica, Longreads, The Rumpus, Catapult, Google Arts & Culture, and elsewhere.

~~~

Publisher information

Don’t Answer When They Call Your Name is set in a fantasy multiverse rooted in Igbo mythology—imagine The Hunger Games set in Ben Okri’s The Famished Road. This is a story about an Aja who decides that it is time to wrest power from a merciless deity.

When the streams suddenly run dry in Ani Mmadu, the people know it is time to atone for a sin that goes back to the very beginning of their world; the consequence of one woman’s rebellion against the all-powerful and unforgiving, jealous god. To avert this catastrophe and for the waters to flow and nourish the farms again, the people must send an Aja—a child chosen by the Oracle—into the Forest of Iniquity, to atone for that great Sin. It falls on young Adanne to save her people this time. But the Ajas sent into the dreaded forest tend never to return. Is Adanne the long-awaited one who will buck the trend and end her people’s suffering?

Don’t Answer When They Call Your Name is an extraordinary novel bursting with kaleidoscopic worlds and beings. It is a feat of the imagination from a natural storyteller.