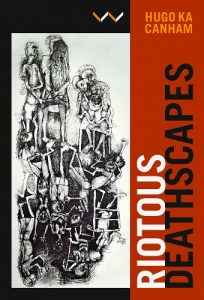

The JRB presents an excerpt from Hugo ka Canham’s forthcoming book Riotous Deathscapes, to be published mid-May.

Riotous Deathscapes

Hugo ka Canham

Wits University Press, 2023

Read the excerpt:

To be relegated to the margins is to be in a state of being perpetually emotionally charged. Feelings coursing near the surface. Catching feelings. Shackled to emotions. In a defensive posture. Touchy. Surly. Chips on our shoulders. Charged in ways that those who are fully human do not have to be. Charged in ways that surprise others. Seeing into the past and future and connecting invisible but sedimented histories of trauma. Over-analyzing. I write this book from the place of catching feelings. From the chip on my prickly body. From the disorientating vortex of repeated catastrophe and joyful paradox that is the black condition. This book is about amaMpondo people of Mpondoland, but it is also about black people who are subjugated throughout the world.

Mpondo Orientations

My mother’s life is lived quietly in the former Transkei apartheid homeland, in deep rural Eastern Cape, South Africa. We are generally referred to as the Xhosa people. To be more precise though, we are Mpondo people who speak a derivative of isiXhosa or isiMpondo. In my mother’s village of Emfinizweni, electricity arrived in 2006 when she was about sixty-five years old. Piped water is a pipe dream. Her candlelit life has been marked by repeated trauma. In the last few years she has fallen on her back at least eight times. In the first of these falls, in 2011, I was with her. She landed with a thud that fractured three vertebrae in her spine. On this occasion, the two of us were marooned in a flooding valley. At her insistence, I stopped the car that we were travelling in. She was worried that the wheels of the motor vehicle would miss the overflowing and crumbling bridge and we would plunge into the river that had burst its banks. She climbed out of the vehicle and after a few steps in the thick mud, she slipped and fell, landing on her back. The falling rain washed the mud from her face as she lay looking into the weeping sky. Her wet hair clung to her forehead, a forehead whose design inspired my own. Beside myself with fear, I extricated her from the mud. Her mouth froze and her breathing stopped. Desperation struck her eyes. A heart attack, I thought. Leaning into her frozen body, I held her mouth and breathed my panicked breath into her—giving her the air that she’d bequeathed to me before my birth. I would later learn that this was the beginning of heightened panic attacks and not a heart attack. I liken this to the Rwandan condition ihahamuka—which means without lungs and is common in the wake of trauma such as genocide. My mother and I did get out of the valley. But faced with roads that jut dangerously out of slippery hills and overflowing riverbanks, my mother lay in bed with a fractured spine for four days over Christmas before the roads cleared sufficiently for us to take her to the hospital. The conditions where people eke out livings in the rural Eastern Cape make black trauma, kaffirization, a quotidian event. My use of the term kaffirization is to signal the work of the term beyond the taboo. Its use has always been pejorative. I use it here to point to its unhumaning intent.

In a fall in 2015, my mother was shoved over by a young man wielding a smoking gun at her face. She landed with a thud to her head. She screamed cries that echoed in the distance to signal to my younger brother to escape from the house. Forcing her to the floor, her attacker tramped on her chest, forcing her ribs to yield, until she quieted. Hearing the screams and gunshots, my brother gathered his crutches and stumbled out of the back door, swinging on his single leg. He hid in the garden, and using his mobile phone, he called for help. My mother has screamed for help in agony so many times that her jaws have a way of locking. This is a sign of panic setting into her body. Freezing her. Draining the air from her lungs. Attacking her. Her screams carry memories of her husband, our father, who died young. I was six then, and my brother was a year old. She has been attacked so many times that she sits near windows to scan the road for assailants. Every sound must be accounted for. ‘What was that?’ The remote control resides in the folds of her lap ever ready to mute the television. ‘Did you hear that?’ She no longer watches the news and violent scenes on the television. Violence triggers panic. She flips through the channels to avoid bad news. Her favourite television programs are those whose dialogue she cannot hear. She sits and watches in the darkness late into the night, willing and repelling sleep, waiting for gunshots so that she can hobble away because she can no longer run. She is afraid to fall asleep. The trauma has eaten into her bones and resides in her joints, swelling and crystallizing them with arthritis that makes her body ache and age. Her diminished immune system means that the slightest cold gives way to pneumonia. The large bump on her head has subsided now. Through her snow-white hair, her scalp glistens in pain. She is no longer conscious of pain in her ribs. A pain that would wrack her body with every inward breath she took. Her diaphragm heaving with the movement of her lungs. Crime is rampant. Unemployment supported by neoliberalism’s insistence on separating people from land and self-dependence has alienated the youth and is driving them to attack the vulnerable bodies of the aged and debilitated. Young men prowl for money. Raised in a violent historical arc of political, masculinist force, violence is a familiar and ready tool.

My brother, too, knows trauma intimately after multiple encounters. From the car accident that led to his amputation to the stabbing of his abdomen and head and the multiple robberies. Kaffirization is when the doctor does not recognize that a vein needs suturing and applies plaster of paris instead. When the leg becomes gangrenous and the rural hospital cannot do anything about it because it has almost no medical personnel and inadequate medical supplies. When rural life is so cheap that it goes to hospital to die. When it became apparent that my brother’s leg was in danger, an ambulance was miraculously found and after a night and ten hours of driving through the rain and mist, my brother arrived first at Mthatha’s Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital where he couldn’t be helped and then in Durban where he was dropped off at Nkosi Albert Luthuli Academic Hospital. From one Nobel Peace Prize winner and antiapartheid hero to another.

I found my brother unconscious on a stretcher in the emergency department of the Durban hospital. He was unattended while his leg decomposed, because the doctor wanted his next of kin. I was told, ‘ To save him, we need to amputate the leg.’ Here I was, faced by the literal non-choice between gangrene and amputation of which James Baldwin (1984) once wrote. The world spun, sweat surged through my pores. My star athlete, twenty-three-year-old little brother whom I had watched learning to crawl and then to walk. And then run like the wind. My brother whom I had cheered as he won all his races at school. I signed the documents and authorized the amputation. Because the gangrene had spread, they cut high. Above the knee. We told him when he regained consciousness. When the phantom pains wracked his body, we coaxed the leg and told it that it was gone. Talking to the (absent) body. Pleading for the brain to catch up to a past that is ongoing. Two years later, the same body and brain had to process stab wounds. Someone waved a car down when they saw him stagger onto the road with his intestines pushing out of his abdomen. In recent years, we have started to worry for his liver, battered by all the drinking. For brutalized young men, drinking alcohol is not a passing relief or rite of passage into adulthood. It is constant because there is no relief for the haunted.

We worry about my mother and brother. We coax them to move to the city where safety can be purchased at a price. They refuse. They are attached to place and land, graves, the river, and the hills that encircle my home. They are disoriented when they are away from the place they call home. The hills enfold them, and the rivers imprison, soothe, and protect. As for me, I witness the deaths and regular brutalization from both near and afar. Sometimes I am at home with my mother. At other times I was in cities such as Cape Town, Durban, and Johannesburg where I have studied and worked. I escaped the fate of most black people that I was raised with because of these movements that have assured a middle-class life of relative safety. I now live in Johannesburg and consider myself to have two homes: one in Johannesburg and one in the village.

Mpondo Orientations

Riotous Deathscapes is the story about the failures of modernity in a place with alternative modes of being that looks to different timescapes and defies death/life binaries. The different chapters suggest that while the incursions of modernity leave devastation in their wake, the Mpondo people make meaningful livings of survivance in the black deathscapes that mark this place. Riotous Deathscapes crafts a Mpondo theory. This theory is conceived in the confluence of the natural world and the jostle of oral narratives against officially sanctioned histories. Its components are a constellation of death, life, the ocean, hills, rivers, graves, and spirits. The theory therefore moves against anthropocentric struggles that invest in the human taxonomy of the Chain of Being. Amid the multiple dyings in Mpondoland are a defiant people whose timescapes root them in a temporality that rubs against colonial time. What emerges is a livingness that points to blackness and indigenous life precariously unmoored from modernity. We witness a hopelessness that does not surrender to helplessness. This is an ethic of black indigenous people. It is a refusal to languish in a state of victimhood but instead craft rampant dying as a way of living. Riotous Deathscapes suggests ways of attending differently to black life on the margins. It offers ways of looking askance as a methodology for black studies from the African continent in conversation with those in the black diaspora. To attend askance is to attend queerly, not in the tradition of Western queer studies but in a queerly African way of looking. To be queerly African is to fail at being a self-contained and actualized modern subject. It is to be in relation to multiple others, to eschew the linearity of settler time, and to refuse social formations that are made for Man. To live queerly is to stay in struggle without seeking escape and transcendence. It is to be both black and indigenous, always porous to possibilities of being remade over time. It is to live in the tributary and confluence of varying crosscurrents that signal relation. Oceanic, spiritual, climatic, death, life, erotic, queer. It is to be attentive to emergent geographies of gendered, sexual, transnational, and racial identities that arise in the wake of rupture. Riotous Deathscapes charts a course of black life in vast deathscapes. It is a portrait of life among the dead.

~~~

- Hugo ka Canham is a writer and professor of research at the University of South Africa’s Institute for Social and Health Sciences and co-editor of Black Academic Voices: The South African Experience. He studies the phenomenology of living at the margins of human value, suffering and death.

Publisher information

‘This is, quite simply, one of the most remarkable books I have read in a long time. Written in anger, despair, and disenchantment, this book is nonetheless about hope. From the spectacularly scenic but stunningly poor South African region of Mpondoland, Hugo ka Canham finds what he calls Mpondo theory, a body of knowledge that eschews capitalist notions of ownership and instead favours communal, environmentally conscious uses of the land and the ocean. If South Africa has been waiting for the postapartheid text par excellence, the sad, powerful, and insightful Riotous Deathscapes could well be that text.’—Jacob Dlamini, author of The Terrorist Album: Apartheid’s Insurgents, Collaborators, and the Security Police

‘Hugo ka Canham’s Riotous Deathscapes is a Mpondo theory-method that “looks askance”, “crafts rampant dying as a way of living”, and “draws on black and indigenous ways of being and resisting”. Canham’s work is particular (to Mpondoland and then to other African and global South communities) and it is diasporic; it is a profound vernacular theory of being in an antiblack world.’—Christina Sharpe, author of In the Wake: On Blackness and Being

In Riotous Deathscapes, Hugo ka Canham presents an understanding of life and death based on indigenous and black ways of knowing that he terms Mpondo theory. Focusing on amaMpondo people from rural Mpondoland, in South Africa’s Eastern Cape, Canham outlines the methodologies that have enabled the community’s resilience and survival. He assembles historical events and a cast of ancestral and living characters, following the tenor of village life, to offer a portrait of how Mpondo people live and die in the face of centuries of abandonment, trauma, antiblackness and death. Canham shows that Mpondo theory is grounded in and develops in relation to the natural world, where the river and hill are key sites of being and resistance. Central too, is the interface between ancestors and the living, in which life and death become a continuity and a boundlessness that white supremacy and neoliberalism cannot interdict. By charting a course of black life in Mpondoland, Canham tells a story of blackness on the African continent and beyond.