Siphokazi Magadla reviews Violence and Solace: The Natal Civil War in Late-Apartheid South Africa by Mxolisi R Mchunu, a book that moves us away from statistics to give a language to how violence and its intimacy are understood.

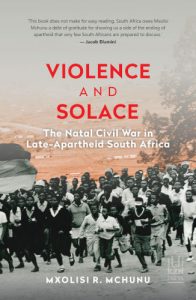

Violence and Solace: The Natal Civil War in Late-Apartheid South Africa

Mxolisi R Mchunu

UKZN Press, 2020

My childhood friend

My childhood friend Nolwazi died inside a car

Numerous bullets went through her body

It was alleged that she was killed by Duma

a man who was my classmate in grade six.

Duma, my classmate in grade six, the story continues

Shot my childhood friend Nolwazi after he shot her husband Mdu

Who had been driving their car, on their way home

Mdu was my brother Malusi’s mlabalaba buddy.

My grade six classmate Duma was not alone at the scene

He was with his com-tsotsi friend, a fellow football player Nkosana

Whose job was to organise a group of com-tsotsis in the community.

Nkosana was my cousin Zazi’s first boyfriend.

Nkosana I remember clearly was once a sweet boy

with a big black birthmark on his forehead,

full of humour, loved by many in our neighbourhood

He lived next door to my childhood friend, Nolwazi.

My childhood friend Nolwazi and her husband Mdu

Were with their three year old daughter Fikile

She too (a potential witness) died, after a shot in the head fired—

it is alleged—by Duma, the man who was my classmate in grade six.

—Makhosazana Xaba (Published in the anthology To Kingdom Come: Voices Against Political Violence, edited by Rethabile Masilo, 2016)

Makhosazana Xaba read this poem at the Poetry Africa festival in 2015. She explained that in the early nineteen-nineties,

One of the things that happened in this province, in the Midlands, when the rest of the country was excited about the rainbow nation, and the Mandela magic, was the violence. The media called it ‘black on black violence’, but of course we knew what was behind it. But people died. Thousands and thousands of people died. And what was frustrating for the people in this province is that the country was far too excited.

I was reminded of Xaba’s poem when I read Mxolisi Mchunu’s book Violence and Solace: The Natal Civil War in Late-Apartheid South Africa.

The work presents a historical overview of the violence in Vulindlela, KwaShange Location, known as udlame, between 1985 and 1996. What Mchunu refers to as the Natal civil war is a reference to the conflict between Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) and the African National Congress (ANC)-aligned United Democratic Front (UDF), which led to the death of an estimated 12 000 people and the displacement of 200 000 to 500 000 people. Mchunu’s book, like Xaba’s poem, moves us away from the statistics to the men, women and children who lived through these years, to give a language to how they understood the violence and its intimacy, how they survived it, and how they have found solace two decades after the end of the conflict, even as its survivors have found no justice.

Mchunu was eight when the violence started. He combines his training as a historian with his personal experience of the atrocities that defined his childhood and forever changed his family and community. Academic studies of the political violence in KwaZulu Natal are often written by researchers, most of them white, who have no personal connection to the place and the experience of violence. What Mchunu calls the ‘inside story of KwaShange, told by two of its survivors’—his mother and himself—forms part of a growing body of autoethnographic studies by African researchers.

Mchunu makes it clear that the civil war happened in the homestead. To avoid being attacked, Mchunu’s mother took him and his three siblings to sleep in a forest. They would return home at 4.30 in the morning, so that his mother could prepare to catch the bus to work as a domestic worker in the white suburbs at 5.30; and the children could prepare for school. This is how families negotiated the mundane—work, school—amid the immediate threat of violence.

Mchunu argues that both ‘Inkatha and the UDF were equally vicious with each other and the state exacerbated the situation’. Both groups were controlled, at least in part, by warlords, and Mchunu observes that ‘to date, there is no warlord in the Midlands who has accepted blame for violence committed by their supporters’.

By looking at the roles of four prominent local men, Mchunu is able to show how national politics played out in KwaShange, leading ultimately to ‘the breakdown of this community into civil war’. Two of them, Moses Ndlovu and Philip Thabethe, had ‘belonged to one church, played for one soccer team and exercised together as young men’. The other two, Nunu Mchunu and Chris Hlengwa, had also been friends before becoming political rivals.

What led to the KwaShange massacre in September 1987, known as ‘Ulwesihlanu Lwezibhelu’ (the Friday of Killings), was a preemptive attack by Hlengwa’s supporters on a homestead containing thirteen Inkatha Youth Brigade members who were alleged to be plotting an attack on the Hlengwa home. Upon arriving at the homestead where the youth had gathered, ‘one of Hlengwa’s men locked the door of the house from the outside and started shooting and throwing stones. One of the bullets hit the gas cylinder and it exploded.’ Mchunu contends that the massacre ‘marked the beginning of the end of “normal life” in KwaShange, Vulindlela and the province in general’.

By examining the evolution of violence in one community, Violence and Solace makes a significant contribution to a growing literature that illuminates the national and local manifestations of udlame. Mchunu’s book is a project of naming. He names udlame as a civil war, whose legacies endure. For Mchunu, the men and the boys were the combatants. He refers to the women as ‘non-combatants’ and ‘witnesses’—albeit to a war that ‘moved out of the battlefield and into every corner of civilian life’. I am suspicious of this depiction of women as ‘non-combatants’ in a war fought in their own homes. Mchunu’s interlocutor, Jill E Kelly, in her article ‘“Women Were Not Supposed to Fight”: The Gendered Uses of Martial and Moral Zuluness during uDlame (1990–1994)’ (2015), complicates this portrayal by calling attention to the fact that some mothers would dress their sons as girls, so that they would not need to remain in the homestead to fight, instead being permitted to flee to hiding places with their mothers. In addition, some daughters stayed behind in the homestead to protect their fathers. As Kelly argues, it is likely that ‘women may have picked up weapons in offence or defence but chose not to share this in their interviews, as they thought it would not be proper for Zulu women to do so’.

Violence and Solace contains a moving chapter that considers the substance of women’s dreams before and during the time of udlame. By doing this, Mchunu underscores the significance of dreams and visions in the African domain, where they are understood to be a link between the living, the ancestors and the creator, uNkulunkulu. As Ezra Tisani explains, in his thesis on Nxele (Makhanda) and Ntsikana, two nineteenth-century Xhosa prophets who were central actors in the Frontier Wars between the amaXhosa and the British in the Eastern Cape, the initiation process of a new inyanga includes a daily ‘exchange [of] information on dreams’, where they would be ‘analysed and interpreted’.

One of the women whose visions Mchunu discusses in Violence and Solace, MaZuma Khanyile, talks about dreaming of a ‘spilling of blood’ in 1985. She explains: ‘From then we began to have women’s prayer meetings in the area, every Thursday. After uManyano gatherings from our respective denominations, we would meet and pray against the evil we saw in the form of a vision’. These women’s dreams of coming trouble remind me of Lieketso Mohoto’s discussion of the concept of ‘uvalo’, which refers to ‘the fluid meaning of intuition’, also known as ‘Umbilini’ among Xhosa-speaking people and ‘Letswalo’ among Sesotho speakers, that ‘promotes a deep sense of knowing’. Mchunu affirms that these women’s dreams revealed that the times were ‘muddled’ (‘ukudunga’), a sign that their ‘bodies, their homes, their families and their sense of community’ would be ‘stirred up under attack by forces threatening to kill them’.

Mchunu also considers the use of muthi and ritual murder to provide a language for what he called, in an earlier publication, a ‘conspiracy of silence […] concerning the continuation of ritual murder and the use of body parts in war-doctoring’ during the violence. He outlines the central role played by izangoma (diviners) and izinyanga (traditional healers), who are alleged to have ‘sold body parts’ to this end. Among the ritual murders he describes are ukuqaqa, which is the ‘custom of disembowelling a fallen enemy’, and ukuhlabana, which is the ‘stabbing of the corpse after it was dead’—a ritual that was historically used when a group of men succeeded in hunting down a dangerous animal: ‘the act of participation was recognised when the men each came up and stabbed the dead beast’.

The people of KwaShange, as Mchunu’s book indicates, believe that this period of bloodshed should have been followed by a ritual cleansing. Instead, known perpetrators of the violence were rewarded with political office. Of the central political parties and leaders, none have accepted responsibility or been held accountable.

Last year, after receiving well wishes for his ninety-fourth birthday from the ANC in KwaZulu-Natal, IFP founder Mangosuthu Buthelezi expressed that what happened in the Natal Midlands was a ‘tragedy’, and that the IFP and ANC must ‘accept the need for healing’ and ‘embrace the path of reconciliation’. As Mchunu argues, however, ‘it may be unjust to ask victims to forgive if perpetrators do not express regret and remorse’.

In the book Autobiographical International Relations (2011), Naeem Inayatullah asserts that ‘working within the overlap between theory, history, culture, and autobiography … increase[s] the clarity, urgency, and meaningfulness of scholarly work’. Accordingly, Violence and Solace makes a significant contribution to the scholarly literature of political violence. It illustrates courageously how families, neighbours and communities were drawn into a battle to ‘win a seat at the negotiation table’—at any cost. The anthropologist Carolyn Nordstrom, in her book Shadows of War (2004), recalls asking a nurse in Angola about what one needed to know to understand that country. The nurse responded: ‘You need to understand death […] Everyone here is on intimate terms with death; everyone has lost someone they love to the war—death walks everywhere with people.’

Mchunu’s book is a reminder that for the survivors of apartheid, almost three decades later, ‘death walks everywhere with people’.

- Siphokazi Magadla is Associate Professor and Head of Department in the Department of Political and International Studies at Rhodes University. She is the author of the book Guerrillas and Combative Mothers: Women and the Armed Struggle in South Africa (UKZN Press, 2023).