Wamuwi Mbao reviews The English Understand Wool by Helen DeWitt, a book that contains ‘one of the most alarmingly enjoyable literary moments I’ve experienced in a long time’.

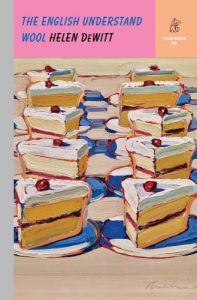

The English Understand Wool

Helen DeWitt

New Directions, 2023

This is a review about a short novel. Short novels elicit a degree of suspicion in many people. The novel is, after all, a machine for finding inventive ways to describe our deepest preoccupations back to us. A short novel thus feels like a bit of a rebuke: it seems to say, ‘we’re not as complex as we think we are.’ However, some of the best works in fiction happen in one or two withheld breaths. Think of Alex La Guma’s A Walk in the Night, James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room, or Annie Ernaux’s brief, beautiful memory-novels (belatedly floodlit by the Nobel Prize), or the captivatingly truncated works of Cynan Jones. In an age of noisy, brimming contemporary fiction that is given its impetus by the chaotic meshing of inner and outer worlds, the short novel does well to distinguish itself. This is not so much a complaint as it is an observation: many contemporary novels feel like they’re on the make, straining to hold your attention long enough to impress you with the way they work through the question of how a person should be in the world.

Helen DeWitt’s novella The English Understand Wool is a refreshing shift in direction. A superb macaron of darkly satirical fiction that runs to sixty-four pages, the novel enfolds a hilarious story about a gamine a la Francoise Sagan into a hilarious skewering of the mendacious publishing industry. Plotwise, the book follows Marguerite, in whose personage is invested a great deal of social observation. Raised by her mother (or the woman she believes to be her mother) in conditions of utmost wealth, the aristocratically chic Marguerite seems every bit the ingénue, sophisticated in matters of etiquette and haute couture—’If one goes to Ireland for linen, which is, of course, unavoidable, one must avert one’s eyes from the monstrosities perpetrated’—but unschooled in how things ‘really’ work. To be sure, Marguerite has spent her short life under the guidance of her ‘Maman’, jetting between Marrakesh and Paris, or pony-trekking for six weeks at a time in Wales—’In England […] it is important to ride as though one had been riding from the age of five, or rather it is important if one is invited to a country house, and the simplest method is, of course, to be taught to ride at the age of five’—in expectation of life continuing on in its hand-stitched, gold-paved way. But when Marguerite is suddenly pitched into peril by a shocking turn of events, our narrating naïf is forced to rely upon what seems to be her only resource: her story.

What initially seems like a cruel revelation (that she is, without warning, penniless and bereft of guidance) turns into an opportunity, albeit a barbed one. Pursued in the street and badgered by agents, producers, publishers and other avaricious types eager to turn her story into sales, Marguerite—reluctant to subject herself to further scrutiny—believes that ‘a book, a text, this is something one can control’. On the urging of ‘a man in New York with a reputation for getting impressive deals’, she flies to that city on the promise of publishing a splashy tell-all. ‘Sympathy’, her new manager tells her, ‘is the key to the whole project.’ Within a week, there is a seven-figure book deal for the North American rights to her story.

What unfolds next is an instructive bit of fiction as well as a terrific satire. The ever-quirky, always opinionated Marguerite drives a story forward that is not, as it initially promises to be, about the crime that catalyses the plot, but actually about the unethical manipulations of the adults who need Marguerite’s story to be as sordid as possible in order to recoup their pound of flesh. It’s a novel that happens in New York without being a New York novel. It’s a novel about writing that isn’t starry eyed with its own cleverness. And it’s hilarious.

In an age where everyone is constantly using an ironic voice, the humour in The English Understand Wool arches towards an older comedic mode. On this small canvas, where every line is doing a job, the effect is exquisite, provoking the same temporal confusion one might experience during an episode of Archer. What is the timeframe of a novel in which the young Marguerite excogitates that ‘It is good for one to be reminded of the depths of idiocy to which one can sink even when, or perhaps particularly when, one means well’—? The style of the novel is one of its highlights—it is both well crafted and elegant, and the hilarity of each rapid chapter (one reviewer likened the pacing to a Howard Hawks film) never falters.

In the end, The English Understand Wool is an immensely enjoyable novel of manners, but the term as it operates in DeWitt’s book is more mockery than description: it lampoons the risible vacuity of the contemporary preoccupation with moral relatability in literature. As a gap begins to emerge between what has happened to Marguerite, and what she is prepared to say about it, her publishers begin to agitate for the kind of expressiveness she seems reticent to give. A false-ringing mail from her editor goes:

Hi Marguerite

This seems like a lot of backstory, making the reader wait for the main event. If you don’t talk about your feelings, there is nothing to engage the reader and keep them turning the pages. I get the impression you’re still bottling things up. Would it help if the two of us met and talked and I just recorded you on my cell to get it all down so there’s something to work with? Or maybe you should skip ahead to the point when the truth came out?

Bethany.

Marguerite is nonplussed, musing, ‘perhaps there were people who would like to hear about feelings, but I did not think they were people I would want to know.’ At first, we fear for Marguerite, alone in deep water as the sharks begin to circle. But our dawning realisation that Marguerite is not who everyone has reckoned her to be, is one of the most alarmingly enjoyable literary moments I’ve experienced in a long time. We think we know who she is, because the novel has piled up a richness of details about Marguerite, but the details don’t mean what we think they do. DeWitt’s superlative narrative control is flaunted here. What we don’t know about Marguerite’s inner depths is as moving as if she had been written over five hundred pages.

In this regard, The English Understand Wool pokes at certain readerly entitlements with a sharp cudgel: what do you think you’re entitled to learn about a character, for them to become whole to you? What aspects of their story do you need to hear for a work to be believable? This is not a minimalist work: far from it. What it does give us, it gives in an articulately maximalist way. Or at least it appears to. The novel’s great trick is to present itself as ambiently digressive, while the actual plot slips along with a lithe exactitude. Here is the first paragraph:

My mother sat on a small sofa in our suite at Claridge’s, from which the television had been removed at her request. She held in her lap a bolt of very beautiful handloomed tweed which she had brought back from the Outer Hebrides. She had in fact required only a few metres for a new suit.

Not only is this striking set-piece a masterly literary characterisation (why the television? Why the tweed?), but it is also an example of how to pressurise a scene by what remains off the page. As Marguerite herself says, it ‘makes intelligible’ that their lives have a certain luxurious texture that will never be fully fleshed out in the narrative. Marguerite, with her quirkily humane intellect and her inventory of fine opinions, never wobbles emotionally before us, and this unflappable elan is never presented as a neurotic quirk. Rare is the contemporary novel that allows its protagonist’s emotional quiddity to remain undisturbed, and DeWitt’s writing is positively sensuous with the tactility of its withholding.

Reviews of this shock of a novel have made deserved reference to DeWitt’s underappreciated status on a Western literary scene that gives its approval sporadically and tiresomely neglects good work. There is indeed much to be said about the failure to appreciate DeWitt’s fine-wired writing, with the author seemingly doomed to that unfortunate category, the writer’s writer. To label a writer with that calumny is almost always to say something about one’s own elevated tastes. DeWitt’s work certainly deserves better than to languish, and with The English Understand Wool she has distilled what is so very pleasurable about her fiction into an essential read.

- Editorial Advisory Panel member Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on Twitter.