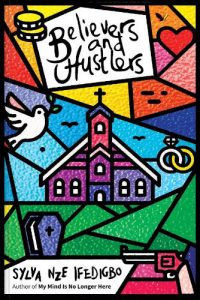

Believers and Hustlers by Sylva Nze Ifedigbo, winner of the Chinua Achebe Prize for Literature, explores the sinister underbelly of organised religion in Nigeria, writes Jerry Chiemeke.

Believers and Hustlers

Sylva Nze Ifedigbo

Parresia Publishers, 2022

In African public discourse, religion is always a hot topic. With the proliferation of fierce and polarising views on the subject, it is an easy way to generate engagement in mainstream media, whether for the purpose of pushing relevant conversations, or just seeking eyeballs.

Discussions surrounding Christianity in particular have the potential to be fire-starters. Imported into the continent centuries ago, the religion has assumed a militant, vibrant flavour in these parts. The TV evangelists from the nineteen-nineties and early two-thousands have morphed into influential statesmen, with congregations the sizes of small nations. From theatrical displays in Durban to miniature concerts in Lagos, Africa’s clergymen move like rock stars, and judging from the opulence and flamboyance that is frequently on show, they may as well be.

It has been argued that the human urge to reach out for a higher power, when placed side by side with a grim economic reality, is the main reason people on the African continent are heavily tethered to religion. Hope is a potent drug, but when churches are run like protection rackets, there is a lot of questioning to do.

These are the dynamics that Nigerian writer and columnist Sylva Nze Ifedigbo puts under the microscope in his Chinua Achebe Prize-winning book Believers and Hustlers. Published in 2020 (but released in 2022) by Parresia Publishers, with editions in the United Kingdom (Abibiman Publishing), Canada (Griots Lounge) and the United States (Iskanchi Press), this compelling novel attempts to encapsulate the look and feel of modern-day Christianity in the world’s most populous black nation.

The impetus of the book derives from Ifedigbo’s characters, who are driven by avarice, ambition, vengeance, paranoia and desperation. There’s Pastor Nicholas Adejuwon, the head of Rivers of Joy Church, the largest megachurch in the cosmopolis that is Lagos, who is armed with the requisite humble beginnings, as well as wit, charisma, and his wife Nkechi as arm candy. He dreams of transforming his ‘cathedral’ into an empire, and there is little to stand in his way: he has his flock in the palm of his hand, and he has the ears of the country’s bigwigs. His hypnotic sermons do not preclude him from a few sporadic indiscretions, but he is able to keep everything in line. Then we meet Ifenna, a brilliant albeit struggling journalist, who has his curiosity piqued by a mysterious death that takes place on Pastor Adejuwon’s church premises. When he asks the ‘wrong questions’ at a press conference hosted by the clergyman, his decision to veer off script costs him his employment, and he resolves to deploy his storytelling gift to launch a crusade against fraudulent men of God. Nkechi, meanwhile, is perennially incensed by her husband’s infidelity but determined to keep up the appearance of a model couple. However, when she caves in to her friends’ suggestions and decides to investigate her husband’s philandering, she discovers secrets far more dangerous than she imagined.

Ifenna watched as his mother became another person. One Sunday, she took them to a different church, which they had to take a bus to get to. The walls were freshly painted in a cream colour and had a smell that tingled the nostrils like insecticide spray … she stopped wearing jewellery and threw away all the rollers she used to curl her hair. She cut her hair low and began to wear a hat that looked like a hair wrap when she went out. She also began to read the Bible so intently and made Ifenna and Nkoli memorise whole verses from a daily devotional that had white people with hair the colour of milk on its cover …

In vivid prose, Ifedigbo explores the murky and sinister underbelly of organised religion. In particular, through the narrative lens of Ifenna, the master-slave dynamic that permeates pentecostal Christianity in Nigeria is laid bare. A young man commits matricide because of a prophet’s utterances. A church worker believes that calling on the name of his pastor’s God will enable his car to operate without the use of petrol. A grieving father is blamed for his child’s death following his refusal to accede to ridiculous demands for sacrifice. A cleric’s apprentice buries items in a family’s compound to set the stage for a phantom deliverance session. As a protagonist, Ifenna may exude a degree of smugness, but it’s difficult not to be enthralled by his cynicism.

What makes Believers and Hustlers tick is how recognisable the events of the novel are as the plot unfolds, and how the narrative resonates through its diversity of characters. Theirs are stories we have read about—sometimes the stories are so on the nose that they could have been pulled from a national daily—but that is what gives the book its soul: it could be anyone’s story. From thieving pastors who get their women members pregnant, to infighting among church leaders who prey on the gullibility of their flock, it’s hard not to regard this novel with a sense of the uncanny, the familiar. Anyone who has ever attended a public university where a student pastor lorded it over members of his fellowship, or read about a revival service where the miracles were clearly staged, will read these pages with something approaching affection.

Ifedigbo doesn’t rely on his subject matter alone to draw his audience in. He could easily have done so—religion’s a captivating topic, after all—but instead serves up a narrative replete with unique back stories and points of conflict, coupled with a deft use of flashback. He deploys the city of Lagos as a character, too, with streets flowing into pubs and police checkpoints in a manner that Cyprian Ekwensi would have been proud of.

The smell of the incense filled the cool night air, driving the solemness of the event into their souls. Then, there was a strong breeze from the ocean that put out the flames on the candles and everywhere turned pitch dark. As he waited for the duo to light up their candles, he heard the loud shrill of a baby crying, which startled him gently and made him drop the pot of incense to the ground …

Believers and Hustlers is by no means a perfect work. There are a few editing sins that a keen editor’s eye should have spotted, there are certain timeline inconsistencies—events that occurred in the early 2010s are lumped with occurrences that played out in 2016—and there are points where the writing feels a little pedestrian. But these drawbacks take little away from an entertaining, well-fleshed-out read. The novel is an advancement on works that have explored similar themes: it runs with more specificity when compared to Olukorede Yishau’s In the Name of Our Father, and it expands on the ideas expressed in Elnathan John’s graphic novel On Ajayi Crowther Street.

It’s a testament to Ifedigbo’s artistic growth, too, that in Believers and Hustlers there’s little sign of the didactic feel that permeated his previous work, the migration-themed My Mind Is No Longer Here. In these pages, Trials of Brother Jero meets People of the City. Is Christendom in Nigeria being pilloried, or is it being subjected to much-needed scrutiny? Dear reader, that’s for you to decide.

- Jerry Chiemeke is a writer, cultural critic and lawyer. His works have appeared in Inlandia Journal, Agbowo, The Republic and The Guardian (Nigeria), among others. A lover of long walks and alternative rock music, he lives in Lagos, Nigeria.