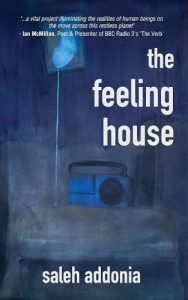

The JRB presents an excerpt from ‘She is Another Country’, a short story from The Feeling House, the debut collection by Eritrean–Ethiopian writer Saleh Addonia.

The Feeling House

Saleh Addonia

Holland House Books, 2022

She is Another Country

1

After the authorities refused us asylum and the court of appeal dismissed our appeal, we went underground. The grounds of our applications were to seek Her. In our applications, we stated that in the country where we grew up she was nowhere to be found so we fled to fall in love with Her.

While we were in the detention centre awaiting deportation, we tried to kiss Her; she was our lawyer. She was the first of her kind to whom we came close, face-to-face alone in a room. She dropped our case and asked us to find another lawyer, but we didn’t bother.

We escaped the detention centre and walked into the city. On our way, we passed a park and spotted Her lying on her back on the green grass, one leg draped over the other. She was wearing yellow underwear, a pair of sunglasses, and was reading a book. We stopped near Her. We stared at her legs in wonder, very seriously. But before we could examine the rest of her naked flesh, she noticed us. She stopped reading her book, lifted her glasses and shooed us off.

We arrived at a contractor’s office—an address we obtained at the detention centre. As if the manager had been waiting for us, he stood up and got out from behind his desk. He was a man in his late thirties, fat but well dressed. He looked each of us up and down.

‘Are you allergic to dust?’ the manager asked.

We looked at each other and said, ‘No.’

‘Do you want to work as street sweepers?’ the manager asked.

‘Yes!’ we shouted.

‘You’ve got the job,’ the manager said and walked back to his desk. ‘You have to work hard. And please remember, you are easily replaceable.’

We were based in the city centre. We each used a two-wheeled trolley bin, a shovel and a brush set. In addition to our uniforms—bright red overalls and gloves—we wore high-visibility yellow vests in the summer or jackets in the winter with bright red capital letters on the back that said:

FOR A CLEANER PAVEMENT

We cleaned in all weather conditions because getting the sack was unthinkable. We worried about our foreman and feared the authorities, though our job eased the latter—we wore our uniforms from home to work and vice versa. We swept dirt off the pavements and curbs with our brushes and shovelled it into our carts. We collected the rubbish from the public bins and took them to collection points. While working, we ignored men and children and observed only Her. And she was everywhere around us. Our eyes enjoyed their new-found freedom as if they were at a banquet; they roved everywhere to spot Her. We were captivated by the variations of her face and its shapes, the texture of her skin. And almost on a daily basis, we would be halted by a sudden spasm with a glimpse of her bare legs or arms or shoulders or cleavage or her well-rounded breasts or bum or miniskirt or tight trousers. We’d always get so excited. We’d feel her image taking possession of every fibre of our being. As if possessed, we’d put our shovels and brushes into our bins, but then we’d remember we had a job to do. Then we’d think it was love at first sight and we’d spend hours talking about it.

We tried to draw her attention to us; we offered her our uninterrupted gazes, we stopped and sometimes bowed for Her to pass while we were sweeping, smiled when we saw Her approaching and on occasions we whistled politely when we saw Her walking on the other side of the pavement or when her back was turned to us. And sometimes we stopped working and took up a particular pose, pretending to look elsewhere as she passed or came out of a shop or appeared from a corner, in the hope she’d notice us.

Whenever we met after work in our room, sitting on the floor or lying on our bunk beds, she was the subject of our conversation. We talked about her face, which we concentrated on while at work so to familiarise ourselves with it. Each one of us tried to remember it and then argued about her hair, nose, eyes and lips. Sometimes we’d look for similarities between the face we’d remembered and the black & white pictures that we’d brought with us from the country we grew up in, which were now hanging on the wall above our beds. Or sometimes we’d look at the cut-outs from porn magazines that we stuck on the remaining walls, or some pictures from the tabloids that we’d look at daily. And god knows how we yearned to look at her bare flesh, beyond the fabric that covered some of her skin, under which we imagined all sorts of things. In our beds, we’d hear each other masturbating every night; our dreams were the same.

One day while we were pushing our carts into the park for our lunch break we saw Her; her head was lying on his lap; he was sitting on a bench. Her eyes were closed; she seemed to be at peace; and he was staring down at her face in silence. We stood nearby and gazed at them without the man taking any notice of us. We left our carts somewhere in the park and sat on a bench to eat our lunch. Half an hour later, we looked at the couple again. The man’s head was still in exactly the same position, looking down at Her and her eyes were still closed. We were astonished. We couldn’t understand how the man would stare down at her face for that long without moving his head an inch. We thought we might have seen love at work. ‘How would it feel if we were in love?’ we asked each other.

‘Perhaps, like him,’ we answered.

In our room, we talked about what we would do if we fell in love with Her. We asked each other where we would take Her. We looked at the bunk beds and underneath the lower beds; they were filled with shoes, food bags and luggage, old tabloid papers, porn magazines and ashtrays. Then we looked at the walls above the upper beds; there our clothes, including our uniforms, were hanging up alongside porn magazine cut-outs. We sat on Surag’s bed and opened the shutters. Through the window, we looked at the tree in the garden, daydreaming. We dreamt of building a small cabin for Her. And we dreamt of Her lying next to us inside that cabin one morning. We’d wait for Her to wake up, and in the afternoon we’d sit under the tree with her head on our lap and we’d stare at her face for hours, like the man in the park.

We looked at each other. We smiled until we could see each other’s teeth. But all of a sudden, we shouted, ‘Aaaaaaaaaargh!’

We went back to our beds, each of us sitting and looking at the one opposite, and we began to cry.

We saw Her thousands of times but she never once smiled, returned our gaze or took any notice, apart from those passing glimpses that weren’t even directed at us but necessary to navigate her way down the street. This was in stark contrast to our thoughts prior to arriving in the country. We thought she’d welcome us. We thought it was simple: Her love.

Over the days that followed, we stopped looking at Her in the streets. At home, we threw away all the pictures of Her on our walls and stopped buying the tabloids. We stopped talking about love and romance. And when we played cards on the floor between our bunk beds, filling the tiny space with our bodies, we tried not to think about Her or imagine Her; we were tired of imagining. But this seemed impossible: We would see her limbs whenever we saw each other’s limbs, our naked hands, legs, chests. Then we’d be afraid and we’d try to cover our faces with both hands. And when we were bored or tired of playing we retired to our beds. Our silence was only interrupted, from time to time, by a cough here or a limb movement there; a leg, hand or head dangling over the bed. The only time we laughed was in the early mornings when one of us would wake up earlier than the others and hide Sami’s hearing aid which he wore on his left ear. Sami would wake up and look for his hearing aid. Then he’d go into fits and shouts and we’d spend 10–20 minutes looking for it with him.

Then came New Year’s Eve. We were in the city’s main square. As the clocks truck midnight, fireworks exploded and lit up the dark sky. Everyone around us jumped up and down, shouting, ‘Happy New Year!’ They kissed and hugged each other and danced. We looked on in silence, then followed the crowd and began shouting, ‘Happy New Year!’ and hugged each other. Then we saw Her in front of us. She said, ‘Happy New Year!’

‘Happy New Year,’ we said.

She kissed one of us on the mouth as we looked at each other with our eyes wide open, and soon we hurried to kiss Her one after another. When we kissed Her, we felt her tongue moving inside our mouths, so we moved ours too. It felt so good when the tongues licked each other. And we couldn’t believe we were sharing our saliva too. Her lips were so warm despite the weather being so cold. And from her lips we tasted alcohol for the first time in our lives. We went on saying Happy New Year followed by kisses on the lips till the early hours.

We and many other street sweepers were cleaning the city’s square on New Year’s Day, early in the morning; we didn’t sleep. All our thoughts were on the lips we kissed the night before. We kept counting them but we never agreed in the final number; sometimes it was 30 lips or 35, sometimes 39, 45 or 50; we had never felt this kind of joy and happiness in our lives before. We felt our journey wasn’t wasted after all.

Later in the night, we discussed the reason for our migration: Her love. We were ecstatic, then got confused, then angry and rebellious. We were lost for days. But we never stopped thinking of the number of lips we’d kissed and we had the urge to kiss more new lips.

‘The question,’ we said, ‘is to love or to fuck?’

We couldn’t understand our question because, if we were honest, we knew neither fuck nor love. But we knew the kisses of all those lips on New Year’s Eve. We smiled at each other. That night we said, then shouted, ‘to fuck!’

~~~

- Saleh Addonia is an Eritrean–Ethiopian writer. He grew up in a refugee camp in Sudan, where he lost his hearing at the age of twelve. He migrated to Saudi Arabia and then to London some twenty years ago. The Feeling House is his first collection of short stories, and has been published in an Italian translation under the title Lei è un altro paese (Edizioni Casagrande, 2018).

~~~

Publisher information

‘There is nothing to forget’

A young girl awakes alone next to a burning truck and befriends a nearby cloud; an Eritrean refugee studies interior design as he attempts to build his new home; a group of illegal immigrants embark on an arduous journey in the city as they desperately seek: Her.

Darting from the dark underbelly of London to the sexually impenetrable home, Saleh Addonia writes stories of displacement and frustration. Tinged with isolation and alienation, each tale strikes the imagination as Addonia weaves the surreal into devastatingly human stories.

With a fable-like wisdom and poignancy, The Feeling House is a compelling, sometimes moving, portrayal of years of a profound disorientation that has fractured time and memory.

‘A vital project illuminating the realities of human beings on the move across this restless planet.’—Ian McMillan, poet and presenter of BBC Radio 3’s The Verb

‘The ultimate refuge for the loss of love and meaning.’—Xiaolu Guo, author of A Lover’s Discourse and writer and director of She, A Chinese