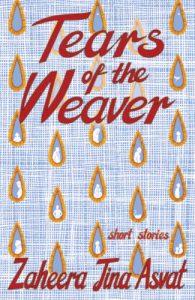

The JRB presents an excerpt from Zaheera Jina Asvat’s short story ‘Birds Kept in Cages, Curse …’, from Tears of the Weaver, her forthcoming short story collection.

Tears of the Weaver

Zaheera Jina Asvat

Modjaji Books, 2023

Birds Kept in Cages, Curse …

Juleikha’s eyes flutter open, and a shiver cascades down the full length of her body into the soles of her ageing feet. She anticipates the events of the day soon to unfold. It is the most auspicious day of the week, Jummah Friday—when, once a week, she performs ablution of the full body and washes the coconut old off her hair before her early morning prayers. The moonlight cascades through the naked windows, casting silhouettes onto the whitewashed walls of her room. The neon green hands of her small, rectangular-faced alarm clock point to the twelve and three. She needs time on her side today, as she has far too much to do. Juleikha climbs out of bed, places her feet into her sandals, and heads in the dark to the bathroom. On her way, she reaches for the steel hanger on the cupboard door handle that holds her Friday attire. She closes the door behind her and places the hanger carefully on the steel screw knocked in at an awkward angle into the height of the door. She takes out a pink plastic comb from the front breast pocket of her dress and places it on the frame of the bath, near the tap.

Still dressed in her full-length white nightdress with embroidered lace at the edges, Juleikha carefully climbs into the bath and sits on the wooden stool facing the tap. She allows only a trickle of water to pass through, then gasps—the water is icy cold. With both hands, she reaches for the heavy bar of green Sunlight soap and rubs it into a lather of white foam. This she smears on a pumice rock and then with her right hand, reaches under the thin wet cotton nightdress close to her bosom, for her left underarm. She scrubs the skin in the pit of her arm almost viciously to wash out all the dirt that has settled there. When she is satisfied that both her underarms are clean, she rubs off the dry skin under her feet.

Beyond the bathroom window, the early morning birds begin to chirp, reminding Juleikha that time for prayer is fast approaching. As if beckoned to their call, she hurriedly unties her long, silver-black plait and combs out the knots that have nested there. She reaches for the pink plastic jug that sits on the rim of the bath, protected in the corner, by the mosaic tiles on the wall, and half fills it with warm water.

Then she bends her head down and tips the jug over her head, allowing the water to flow over and drip down into the drain. Again, she reaches for the green bar of soap which she rubs directly into her scalp, massaging the soap into her hair. Juleikha then opens the tap and sticks her head under. Using all her fingers, she scrubs her hair clean, pulls the strands together, and squeezes the water free. Next, she fastens her green hand towel with the frayed edging tightly around her hair. Juleikha stands up slowly and, placing her right leg out first, she climbs out of the bath. She uses both hands to hold onto the steel shower pole in front of her.

Her now-wet nightdress clinging to her form, she quickly removes her water-soaked panty from under the nightdress and puts on a clean, dry cotton one. Juleikha then unbuttons the nightdress and lets it fall to the floor. She keeps on her wet bra; it will dry soon in the hot December sun. Juleikha slips a clean and long satin, emerald-green dress with matching trousers—her Friday best—over her head. She squeezes the towel around her hair to remove the excess water, then she removes the towel from her hair and bends down to wipe the water that has collected on the floor. Her wet night-clothes and her towel she throws into a plastic bucket which she stores under the black plumbing of the basin sink. She will wash them, later, when the sun paints the sky yellow and bright blue. Juleikha collects her pink comb and returns to the silent confines of the room.

Juleikha is the only one awake in the house—her daughter, son, and daughter-in-law sleep on. It is best to keep everything peaceful and quiet until the house wakes to the bustle of the day. The call for prayer echoes into the night sky. Juleikha rolls out her prayer mat to face the Kiblah, the sacred mosque in Makah. From her cupboard, she carefully pulls out her white hijab with the neat pink flowers patterned on the border. Her hair is still wet and lies in clumps at her nape. She wears the hijab over her head and tightens the elastic at the neck. Patiently, she waits for the final words of the call for prayer before she performs the early morning prayers. She raises both hands together and prays that the pot of biryani that she will later prepare for her daughter Safiyyah’s year-end function is delicious and well received.

Juleikha then removes her hijab and her emerald-green dress and replaces it with a satin slip, and over it her beige- coloured checked apron with the short sleeves. With her comb, she brushes her silver-black hair, threading it neatly into a plait which rests on her straight, proud back. From her cupboard she takes out a square scarf, folds it into a triangle, places it over her head, and ties it below her chin. At fifty, Juleikha looks old; her harsh life has eaten her youth and left her with deep wrinkles, sagging skin, and a bitterness which she wears as gracefully as she can.

The first to awaken is the parrot, Zeyn, and in his cage he shrieks, ‘Norr … ma … wethu! Nomawethu!’ Nomawethu is Juleikha’s neighbour and only friend. Zeyn’s large cage is placed on a small wooden table, in the corner of the dining room, alongside the deep freezer. Juleikha removes the black sheet which covers his cage. After she opens the cage door, she reaches for the bowl which holds seeds. Zeyn’s grey feathers spread out, and he jerks forward. Juleikha backs away from the cage—shocked. Zeyn appears to be attacking her. His unusual behaviour worries Juleikha. She hopes he is not ill.

Once in the kitchen, she fills his seed bowl, and from the kitchen window, Juleikha sees that her neighbour’s house lights are switched on. An inner peace settles with the knowledge that Zeyn has completed his morning duty of waking the neighbours for the day ahead. Nomawethu does not believe that the bird possesses any sense. She argues that that’s what parrots do. She prophesises bad omens when birds are kept caged and often insists that Juleikha let the bird free.

When she returns to the dining room, Zeyn sits upright on the edge of the wooden perch of his swing, which moves back and forth slowly. Jolted back to the present, Juleikha watches Zeyn’s eyes target the bowl which she hold firmly in her hands.

Zeyn is restless and squawks again. ‘Nomawethu! Nomawethu!’ He spreads his wings and then soars towards the cage bars. Juleikha lets out a frightened scream. She instinctively holds out her hands in front of her, rocking on the balls of her feet to steady herself. She opens the cage door and throws in the bowl, scattering seeds everywhere. Zeyn stops his anxious fluttering and falls forward, into the dropped seeds. His body stops heaving, and he becomes very still. Juleikha is frozen to the spot.

The noise has woken Safiyyah, Hoosein, and Rahma. Juleikha watches them coming down the passage.

‘What happened?’ chorus Hoosein and Safiyyah.

Rahma stands in her husband’s embrace.

‘I have no idea,’ mumbles Juleikha. She reaches for Safiyyah’s hand. ‘Zeyn … seems possessed …’

‘Ag, Ma. You know that you are not making sense, right.’ Hoosein opens the door of the cage and prods at the bird’s body with his fingers. ‘He’s breathing. I will take him to the vet on my way to work. Moenie worry nie, all right? Alles sal eventually regkom.’

~~~

- Zaheera Jina Asvat is a writer and an academic. She holds a PhD in mathematics education from Wits University, and is a lecturer at the Wits School of Education. Asvat is the author of Surprise! and the StimuMath programme for preschoolers. She compiled and edited Tween Tales 1, Tween Tales 2, Saffron, and Riding the Samoosa Express. In addition, she is the curator and organiser of Jozi’s Books and Blogs Festival, a non-profit initiative aimed at inspiring expression through reading, writing, and the arts in the less-affluent areas of Gauteng. Asvat lives in Lenasia, with her husband, three sons, and many in-laws.

~~~

Publisher information

In ten superbly crafted stories, Zaheera Jina Asvat takes us into the private, individual worlds of a varied cast of characters and exposes the complicated weave of emotions so often concealed under the veneer of everyday lives.

The stories provide a rethinking of conventions and roles, enabling readers to challenge the social phenomena within the world that religion and culture govern. These stories are earthy, feeling portraits of people struggling against an oppressive system within post-apartheid South Africa.

Bhajee’s concern is a stolen electricity meter on his property, which cannot be replaced because a fictional Mr Ka Ching Ching is the registered owner, and Suhail Mangel, as a victim of xenophobia is worried that his family has cursed him. A Maulana is thought to have a marriage potion in one story and in another a dying parrot that brings bad news. Then there is the woman who in Covid-19 lockdown trying to fathom her broken marriage, a family fighting for inheritance in the face of religious law, the cat who is a bringer of gifts for her depressed owner, the daughter-in-law who questions her role as wife and mother, and the woman who cannot conceive and is offered the option of a surrogate in the form of a second wife.

In this collection, the colourful characters cast their paths through the threads of their own fictional lives, as distraught and jubilant and uncertainly fragmented as any among us, the living.