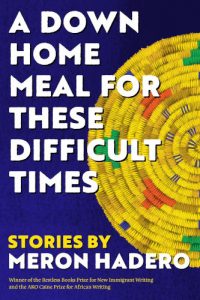

The JRB presents an exclusive excerpt from A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times, the debut collection of short stories from Ethiopian American writer Meron Hadero, winner of the 2021 Caine Prize.

A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times

Meron Hadero

Restless Books, 2022

The Floating House

Gashe Ayeloo and Eteye Amsala’s house, #372, was next door to Amare’s. Gashe Ayeloo’s favorite way to waste a little time was to look out his window at people waiting for the bus; after all, his home had an ideal view of this little cul-de-sac branching off MLK. The house was three stories high and so old it seemed about to fall down, but instead it fell up, floating above the street below. Raised just slightly off the ground, quite literally levitating there. The exact height was two inches, according to Gashe Ayeloo. A small amount, but notable nonetheless.

Eteye Amsala was the first to notice. When she was on her way to her car one morning years back just after they moved in, she tripped. Looking around, she didn’t see anything that would have made her stumble. Not a stone, not a root, not a stick in sight. But she saw a shadow that had not a leafy perimeter, but a root-rimmed one. Eteye Amsala ran back inside, and summoned her husband.

Gashe Ayeloo observed the miracle by leaning over the edge of his property, which he rarely left. Nothing seemed to be holding the house up. He looked overhead, but the answer was not in the sky, either. I thought I’d seen it all by now, he thought, though he wasn’t quite sure what he was seeing. A small crowd began to gather. Yonathan, Amare’s son, got a bag of marbles, rolled one under the house, then ran to the back, and returned holding up that marble, which had gone straight through. At this, the crowd shifted from a position of doubt to one of belief.

By this time, Eteye Amsala was hysterical. She swore up and down and left and right and side to side that she’d never step foot in that cursed abode. She went to church morning, noon, and night, and stayed with her cousin until Gashe Ayeloo protested her absence by fasting. The hunger strike lasted two days, and Eteye Amsala was guilted into coming home, but she couldn’t help but creep softly through the house for fear that she might fall straight down and to who knew where. Eteye Amsala took another precaution: each morning, she’d open the gate and look outside just to make sure they hadn’t finally drifted off to who knew where, either, for confronted with a mystery as peculiar as this, her imagination took flight, understandably.

Gashe Ayeloo’s hovering house was a gossiped-about sight on this slice of the Rainier Valley … for a while. Some who were scientifically inclined thought about conducting experiments. The romantics dreamed this rebellious house was a symbol of wild nature. The bureaucratic wondered whether Gashe Ayeloo should pay more in property taxes since he technically occupied the land around and below his house. The superstitious had their own beliefs and crossed over to the other side of the street as they walked up and down that stretch of road. But as these things go, people got on tending to their own lives in this closed-off, separate corner of what was becoming known as Little East Africa, where signs in languages from around the Horn were juxtaposed over signs in Mandarin and Vietnamese, which were layered over signs in characters too faded to make out. The spectacle of Gashe Ayeloo’s house also faded away, was absorbed and accepted as a neighborhood quirk soon enough.

Gashe Ayeloo accepted it, too, but had to take some practical measures to adapt (he said the pavers shifted on his doorstep more often than was reasonable, and swore more bugs, squirrels, and birds gravitated to his levitating parcel, and they needed shooing away), though he was surprised that the change required very little in the way of maintenance. Otherwise, there was nothing Gashe Ayeloo could seem to do to physically get that house back down, for the mechanism that kept his home suspended was not magic, not science, not an alternate dimension breaking through on this very spot, but a force that bubbled up from the will and internal desire of Gashe Ayeloo, who had set out to never leave Ethiopia, even long after he had gone, long after he’d been cast into exile. In his exile, he recreated his home off MLK Ave. to precisely mirror the first. This reflected house, like his life in the city, and his world itself, did not quite touch down, was neither here nor there.

Gashe Ayeloo’s house wasn’t the only home afloat in this world. There were probably dozens across the city, maybe hundreds across the country, perhaps even thousands across the globe, maybe many more. In fact, if you could look at the world from the side with exacting detail, from a hovering magnifying lens or some such gadget, you’d notice a strange topography of floating houses rising just above the earth, a separate plane of existence right there for anyone to see, should they choose to look. I know this for a fact and can assure you with confidence, for you see, I lived in one such house far from Gashe Ayeloo nearly a century ago and am no stranger to these shifts. I can say from experience that he is not alone. These floating homes constitute not any certain state, not a nation, not a formal country with any government or ideology or agencies that require paperwork and official stamps of entry. This is not a governed state, not even a state of mind, but a state of heart. A certain way of living in diaspora, and dear Gashe Ayeloo was not alone.

With homes like this, there are always those days when the foundation creaks a little, poised to touch down again and re-solidify, rejoin a fuller way of life. When I see Gashe Ayeloo, it makes me wonder, what does it take for a man like this to consider reengaging? For me, everything had to fall apart, and a new life, wholly unexpected, sprung up in its place. For Gashe Ayeloo, how great a force would be needed to nudge him those last two inches homeward?

In the meantime, he spent his days looking out from his window. That morning, as white cottonwood fibers blew through the air, Gashe Ayeloo waved to Tariq whose arms were raised tall and poised, recalling an old, rooted Mediterranean Cyprus, or a rocket set to lift off.

~~~

- Meron Hadero is an Ethiopian American who was born in Addis Ababa and came to the United States via Germany as a young child. Hadero’s short stories have won the 2021 Caine Prize for African Writing, have been shortlisted for the 2019 Caine Prize, and appear in Best American Short Stories, Ploughshares, McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, Zyzzyva, The Iowa Review, Missouri Review, 40 Short Stories: A Portable Anthology, and others. She’s also been published in The New York Times Book Review and the anthology The Displaced: Refugee Writers on Refugee Lives, and will appear in the forthcoming anthology Letter to a Stranger: Essays to the Ones Who Haunt Us. A 2019–2020 Steinbeck Fellow at San Jose State University, and a fellow at Yaddo, Ragdale, and MacDowell, Meron holds an MFA in creative writing from the University of Michigan, a JD from Yale Law School (Washington State Bar), and a BA in history from Princeton with a certificate in American studies.

~~~

Publisher information

Ethiopian American author Meron Hadero’s gorgeously wrought stories in A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times offer poignant, compelling narratives of those whose lives have been marked by border crossings and the risk of displacement.

Set across the United States and abroad, Meron Hadero’s stories feature immigrants, refugees, and those on the brink of dispossession, all struggling to begin again, all fighting to belong. Moving through diverse geographies and styles, this captivating collection follows characters on the journey toward home, which they dream of, create and redefine, lose and find and make their own. Beyond migration, these stories examine themes of race, gender, class, friendship and betrayal, the despair of loss and the enduring resilience of hope.

Winner of the 2021 AKO Caine Prize for African Writing, ‘The Street Sweep’ is about an enterprising young man on the verge of losing his home in Addis Ababa who pursues an improbable opportunity to turn his life around. Appearing in Best American Short Stories, ‘The Suitcase’ follows a woman visiting her country of origin for the first time and finds that an ordinary object opens up an unexpected, complex bridge between worlds. Shortlisted for the 2019 Caine Prize, ‘The Wall’ portrays the intergenerational friendship between two refugees living in Iowa who have connections to Germany before the fall of the Berlin Wall. A Best American Short Stories notable, ‘Mekonnen aka Mack aka Huey Freakin’ Newton’ is a coming-of-age tale about an Ethiopian immigrant in Brooklyn encountering nuances of race in his new country.

Kaleidoscopic, powerful, and illuminative, the stories in A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times expand our understanding of the essential and universal need for connection and the vital refuge of home—and announce a major new talent in Meron Hadero.

‘This book heralds the arrival of a gifted, stunning writer. A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times held me spellbound…These stories unfold with an intensifying power, each of them a testament to what’s possible when we move through this world insisting on the potential of hope, and love.’—Maaza Mengiste, author of Booker Prize finalist The Shadow King

‘Meron Hadero’s collection, A Down Home Meal for These Difficult Times brims with lives on the margins…This style, which time and time again comes off the page as truly effortless, is what makes Hadero a new master of the form, and this collection a masterful one.’—Chigozie Obioma, author of Booker Prize finalists An Orchestra of Minorities and The Fishermen