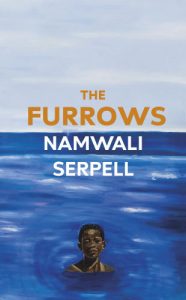

The JRB presents an excerpt from The Furrows: An Elegy, the new novel from award-winning author Namwali Serpell.

The Furrows

Namwali Serpell

Penguin, 2022

Read the excerpt

Over the months, we found more and more of Wayne’s drawings, those bundles of thin lines on the walls. Behind the couch in the den. Under a windowsill next to the upstairs toilet. Inside the door of a high-up kitchen cabinet we never used. Behind the curtains on either side of the living room windows. They were always in pencil, the same three stick figures, sometimes in a series. More like clones than a family. My mother spoke of haunting, but more often of signs.

‘He’s trying to tell us something,’ she’d whisper from inside a cage of her fingers. ‘We have to find him. We have to investigate.’

‘These are old drawings, Char,’ my father maintained. He had taken to painting over each one the moment we found it. He was as adamant about painting over them as my mother had been about throwing out Wayne’s toys. But he didn’t ever paint over the first one they’d found, behind my dresser. I didn’t let him. It felt important to the balance of the situation that it stay there. I made sure I was always too busy in my bedroom whenever he came in the open door with a paint can and brush, a shower of dried paint like a far-off galaxy on his ratty old Marley T-shirt.

‘I don’t like the smell of the paint.’ I’d wrinkle my nose. Or: ‘I’m doing my homework.’ I’d shake my head. Or: ‘Do you have to do it right now?’ I’d look up from a jigsaw puzzle, its mainland flush against the wall he wanted to paint, unfinished islands around me. He left it.

At night, I would investigate the drawing on my own, carefully moving the dresser, lifting it so its scrape on the floor would not betray me. I pictured Wayne’s hand crudely fisted around the pencil, his bottom lip pouting, his tongue peeking out with focus. I hovered my finger over the lines so as not to smudge them. I redrew the figures behind my closed eyes as I tried to sleep. I compared the drawing to the others. I compared it to how that day I had looked in the steamed-up mirror and seen that splotch of clarity in the middle of the fog, a handprint too small to be mine, how I had wiped my hand straight through it.

The day I caught my mother drawing on the walls, I felt a thrill of confirmation. I had come into the study to fetch a pair of scissors and found my mother, on her knees under the oak desk, facing the wall. Her head was tilted so her hair was hanging to one side. I watched her draw a long leg down from a rectangular torso on the wall. Her shoulder bumped the desk leg and she said, ‘Ow’ and giggled to herself. I listened and watched. She began to hum the itsy-bitsy spider song, which she’d recently decided had been Wayne’s favorite. I tiptoed away, my heart thumping triumphantly.

I found my father in the kitchen, bent over a nearly empty fridge, its platinum light making the new white in his beard glint. A packet of frozen pork chops sat on the counter. His lips were parted when he turned and looked at me. He seemed dazed. I told him in a heated fluid rush what I had seen my mother doing in the study. ‘There’s no time,’ I said as I turned to the door, we had to catch her before she finished. My father straightened up but he didn’t budge. The fridge light cast flat ovals on his cheekbones.

After a moment, he began to scold me. He had noticed that I was no longer much of a truthteller, he said. He had noticed in fact that I was always telling tales, like it was some kind of a joking matter, he said. My eyes flooded with wet fury. My ears got hot. He was punishing me, it seemed, for what I had said about my mother. But even as I burned and melted, not saying a word, I knew that my father would not outright call me a ‘liar.’ That word and its variants were considered cusses on his side of the family. Like many children forced to work around the constraints of taboo, my brother and I had always circled ‘lie’ and ‘liar,’ snuck up on them.

‘Don’t be sssly!’

‘You’re the ffflyer!’

And so that day, my father called my news that my mother was drawing pictures behind the furniture and pretending they were Wayne’s any and every word other than ‘lies’ that would still warrant a thorough telling-off. He went through as many synonyms as needed—stories, tales, fibs, nonsense, foolishness—to let all the time in the world pass us by, to let my mother finish her drawing and crawl out from under the desk undisturbed.

- Namwali Serpell was born in Lusaka, Zambia, and lives in New York. She received a 2020 Windham-Campbell Literature Prize, the 2015 Caine Prize for African Writing, and a 2011 Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award. Her debut novel, The Old Drift, won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, the Arthur C Clarke Award for science fiction, and the Los Angeles Times’s Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction. Her nonfiction book Stranger Faces was a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award for criticism. She is currently a professor of English at Harvard.

~~~

Publisher information

A powerful new novel about grief and mourning from the acclaimed and prize-winning author of The Old Drift

I don’t want to tell you what happened; I want to tell you how it felt.

Cassandra Williams is twelve; her little brother Wayne is seven. One day, when they are alone together, there is an accident, and Wayne is lost forever. Though his body is never recovered, their mother is unable to stop searching. The missing boy cleaves the family with doubt: How do you grieve an absence? And how does it feel?

As C grows older, she relives and retells her story, and she sees her brother everywhere: in coffee shops, subway cars, cities on both sides of America. Here is her brother’s older face, the colour of his eyes, his lanky limbs, the way he seems to recognise her too. But it can’t be, of course. Or can it? And then one day, there is another accident, and C meets a man both mysterious and familiar, a man who is also searching for someone, as well as his own place in the world. His name is Wayne.

Namwali Serpell’s piercing new novel captures the ongoing and uncanny experience of grief, as the past breaks over the present, like waves in the sea. The Furrows is a bold and beautiful exploration of memory and mourning that twists unexpectedly into a masterful story of mistaken identity, slippery reality, black experience, and the wishful and sometimes willful longing for reunion with those we’ve lost.