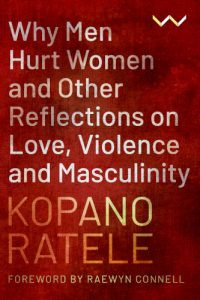

The JRB presents an excerpt from Kopano Ratele’s new book Why Men Hurt Women and Other Reflections on Love, Violence and Masculinity.

Why Men Hurt Women and Other Reflections on Love, Violence and Masculinity

Kopano Ratele

Wits University Press, 2022

Read the excerpt:

‘Brothers, check yourselves!’

It was a Sunday night in March 2015 at Azania House, University of Cape Town. A young woman told the house of how some nights previously, in the middle of the night outside the building, a male student had hollered at her and said, to use her words, maybe her vagina should be occupied. The woman was part of the group of #RhodesMustFall students—the Fallists—who had occupied the building, which normally houses the office of the university’s vice-chancellor and top managers. The occupation and renaming of Azania House was intended to pressurise the university into bringing down the statue of the arch-colonial figure Cecil John Rhodes, which at the time had pride of place on the university’s upper campus.

The woman spoke of how she was threatened with rape. She said she wasn’t the only one who had experienced threats of sexual violence and bullying.

Black brothers,’ the woman then said, ‘check yourselves.’

That was the moment, fastened to four words.

Due to the intricacy of intimacy and confrontation they convey, these words are memorable.

The young woman said she could not sleep another night at Azania House. She felt unsafe in the very space meant for students who dared to stand up against and to bring down colonial symbolic power and make the university a home for all.

She left.

It is not my intention to offer an extended reflection on the 2015 #RhodesMustFall uprising, although the events of that night bring into sharp focus for me some men’s ideas about and relations to women and their bodies, about struggle, about freedom, about power. I have several times visited it in my mind, in academic discussions, in private ones, and in writing this specific moment in which a woman speaks of fear of harassment and violence, and wishes to leave the joint struggle to decolonise universities. For me it is a moment that sparks thinking about how we might work with men and boys toward a pro-feminist consciousness and practice. By pro-feminist consciousness and practice, I mean a sociopolitical awareness in men and boys that supports women’s feminist struggles, and the behaviours that go with such awareness.

A moment like this is significant for those of us engaged in the pursuit of social justice in interpersonal and intergroup life, efforts to decolonise minds and society, and the work of trying to build safe, peaceful, inclusive and thriving institutions and structures. Such a moment, in which we witness threats of violence in the very place where there is supposed to be camaraderie, appears to be very useful for closely examining and trying to understand not just the psychologies of some men, but relations between men and women. A moment to build decolonised institutions. And it is also a moment that I have employed in considering precisely what is needed to draw men into joining intersectional, decolonial feminist women in their fight against a modern/colonial, exploitative, patriarchal, heteronormative, racist world.

As it turns out, it is not easy to turn men into pro-feminists. I have tried. (I am still trying.) This difficulty in making men pro-feminist, making them see the personal and social benefits of gender equality, is, ironically, real even for those men who may have experienced oppression in their own lives as part of a class, culture, sexual group, nation or race. But I should have known. An experience of, for instance, white racism is not a sufficient condition to change a person into a fighter against all forms of oppression, and too often not even against white racism itself. Having suffered from exploitation as a blue-collar worker (for example, working for a bad male boss for low wages, for long hours, in unsafe conditions) usually does not in itself turn a man into an anti-capitalist non-sexist, let alone turn him against all forms of exploitation. The experience of social or economic injustice is not, on its own, guaranteed to radicalise a subject against that particular injustice or against other forms of social injustice. Something else, then—a deliberate education about the effects of the interaction of, for example, racism and sexism and capitalist exploitation on men’s lives—is required.

In patriarchal societies, which include most societies in the world, pro-feminist men can be regarded by other men and women as an anomaly. Men who support feminism in patriarchal societies can be threatening to the status quo. In such societies men are encouraged and permitted to ignore women’s voices and rewarded for doing so. In these societies, then, by definition most men are not inclined to support feminist goals, even when some feminists are willing to work with those same men to the bene- fit and health of men and boys.

I was at the occupied and renamed Azania House because of an invitation from a radical female African social psychologist and a queer feminist, both based at the university. I mention some of their identifications because as a cisgender, heterosexual man I take it as a privilege, as evidence of the possibility of trust, to be invited by queer and heterosexual women to support gender and sexuality struggles.

Both women were closely involved with the movement and in supporting the students. Because of reports of sexual harassment experienced by female student activists, they asked me to facilitate a discussion on patriarchal masculinities among the student activists occupying Azania House.

After a long and bruising engagement with the students, I would leave the space with a feeling that the night had been instructive and intense for me, no doubt. It was, however, far from a success in fulfilling its intention to shift the dominant male voices, meaning the most vociferous in that space. Although some young men wanted to hear more about why patriarchal forms of masculinity might be deleterious for the well-being of males and not only females, the feeling that stayed with me was that it did not seem as if we are very successful at getting into the heads of male youth, let alone changing their practices. Why, I would later wonder—as I have done so many times—do forms of domination persist within spaces precisely aimed at challenging domination? Why is there sexism in the very struggle against colonial, patriarchal oppression? Why is there violence among those who have been violated?

I admit it was with some trepidation that I agreed to facilitate the discussions among the #RhodesMustFall students. I asked questions about whether the students would be receptive to a discussion on patriarchal masculinities. It may be true that, wherever there is sexual harassment and other forms of violence, we ought to always be ready to engage with those who are violent and harass others. However, if under ordinary circumstances most men are disinclined to support anti-patriarchal interventions, the likelihood of turning away from patriarchal masculine practices decreases when they feel obligated to do so. Yet I agreed to facilitate the discussion, because I am persuaded by the view that employing processes such as working through our pain, and conscientising those who have been dehumanised by economic, sexual or racist ideologies, can help people come to realise that they won’t be humanised by hurting others.

My engagement with men is informed by practical experience and by a theoretical appreciation of the workings of socioeconomic power and psychosocial pain. I mean that I am acutely aware of the permeation of structural power into subjective lives. our emotional lives, feelings of insecurity or well-being, are not simply due to our will, to what we do or what happens inside us. What we do, indeed what we are, is constrained or enabled by forces beyond us. Environmental factors, where one lives, the education one has, the money in one’s family’s or one’s own pocket, and the politics and policies of the country structure our lives, but not in a deterministic fashion. That appreciation therefore includes the knowledge that individuals have agency. While some of us do overcome the suffering we may have experienced, others may deal with their own distress and insecurities by wounding those around them.

I have been inclined to believe, wrongly as it turns out, that it should be evident to most victims of white racism that sexism is not a remedy for racism but rather its kin. I have also wanted to believe that individual men who injure women and other men would realise that they are not contributing toward overcoming the capitalist, racist and gendered humiliation they have suffered at the hands of exploitative, supremacist and patriarchal structures.

The assumption that those who have been hurt are supposed to comprehend the effects of violence, and thus should almost instinctively recoil from violating others, is what creates disappointment when we cannot help men swiftly transform their gender practices. A great feat of economically, racially and sexually violent structures is precisely to predispose their victims to hurt each other. Ironically, the violent behaviour of the (formerly) oppressed toward each other may sometimes follow the same lines as the violence of the (former) oppressor: the formerly colonised become neocolonialists, those who were abused become abusers. The same holds for other forms of oppression: individuals repair themselves when they arrive at a psychosocial and sociopolitical place where they are enabled to recognise that, however much they have suffered, the hurt they experienced will not be palliated by making others suffer. I am aware, then, that individuals deal with the hurt they experience from structures and others in a complicated way—people don’t simply rise up and direct their rage at the unfair structures and those who oppress them. Therefore, although it is dispiriting to encounter sexist men, unfortunately there is a rationale for intraracial sexual harassment and violence. This is not an excuse for male violence. Instead, it is on this basis that, in the face of frustration, activists, researchers and teachers ought to work harder and more imaginatively to find pedagogic and conceptual registers through which we can turn young men toward pro-feminist masculine consciousness.

~~~

- Kopano Ratele is a South African psychologist and men and masculinities studies scholar. He is Professor of Psychology at Stellenbosch University and Head of the Stellenbosch Centre for Critical and Creative Thought. Among his previously published books are Liberating Masculinities (2016) and The World Looks Like This From Here: Thoughts on African Psychology (2019).

~~~

Publisher information

A fusion of conversations, observations, and personal reflections on his own experiences, work with men, and scholarship, Why Men Hurt Women and Other Reflections on Love, Violence and Masculinity is Kopano Ratele’s meditation on love, violence and masculinity.

This book seeks to imagine the possibility of a more loving masculinity in a society where structural violence, failures of government and economic inequality underpin much of the violent behaviour that men display. Enriched with personal reflections on his own experiences as a partner, father, psychologist and researcher in the field of men and masculinities, Why Men Hurt Women and Other Reflections on Love, Violence and Masculinity is Kopano Ratele’s meditation on love and violence, and the way these forces shape the emotional lives of boys and men.

Blending academic substance and rigour in a readable narrative style, Ratele illuminates the complex nuances of gender, intimacy and power in the context of the human need for love and care. While unsparing in its analysis of men’s inner lives, Ratele lays out a path for addressing the hunger for love in boys and men. He argues that just as the beliefs and practices relating to gender, sexuality and the nature of love are constantly being challenged and revised, so our ideas about masculinity, and men’s and boys’ capacity to show genuine loving care for each other and for women, can evolve.