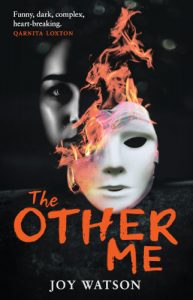

Anna Stroud chatted to Joy Watson about nasty women, how the markers of identity write themselves into our stories, and her debut novel, The Other Me.

The Other Me

Joy Watson

Karavan Press, 2022

Anna Stroud for The JRB: Congratulations on publishing your first novel! How does it feel to have The Other Me living out there in the world?

Joy Watson: It’s a very special feeling. I wrote The Other Me while I was going through an incredibly difficult time. It was a creative outlet to escape the loss, grief and trauma happening in my life. When I look at the book, there’s this warm, mushy thing that happens, sort of like, ‘Hello friend. You saw me through some difficult times, I like you.’

The JRB: Before publishing The Other Me, you edited Nasty Women Talk Back in 2019 with Amanda Gouws—a collection that links the personal with deeply political issues—in which you wrote a beautiful, harrowing story called ‘Pussies are not for grabbing’. What is a ‘nasty woman’ and why is it important for her to talk back to patriarchy? Would you say Lolly, from The Other Me, is a nasty woman?

Joy Watson: I think that it is important for every woman to claim the ‘nasty’ in her at the right time, in the right context. We chose the title Nasty Women Talk Back for the book because Donald Trump had called Hillary Clinton a ‘nasty woman’ when she called him out on his misogyny. As women, we’re socialised into tropes of what a ‘good’ woman is and this can be limiting, it can be destructive in the long term. It’s so important to acknowledge that which incurs our wrath and to know when we’re entitled to our anger, to all the emotions that a ‘good’ woman should supposedly not be allowed to inhabit.

In some ways, Lolly is a nasty woman, in both good and bad ways. She’s manipulative, deceitful and self-serving. But, she’s also incredibly intelligent, savvy, and does not suffer fools gladly. Mostly, though, she’s broken and unwell.

The JRB: In a 2014 journal article on gender-based violence, you wrote that ‘private and public spaces in South Africa have become a war zone for many women’. That’s definitely true for Lolly in The Other Me. Given the turbulent time and place in which Lolly is born and raised, is it any wonder that she becomes such a deeply troubled woman?

Joy Watson: I deliberately set out to create a backstory for Lolly—a backstory that is familiar to many of us—growing up in a socioeconomic context that makes emotional and psychological scarring indelible. While this backstory provides contextual understanding for some of what Lolly does, it does not exonerate her. I try to capture a manifestation of what it might look like to have someone emerge from Lolly’s backstory being deeply scarred and unwell. I do not attempt to resolve the question of whether or not we should feel empathy for her. I work, instead, with moral ambiguity as a literary device. The aim is to ask, ‘Dear reader, what do you think?’

The JRB: The opening paragraph hooked me in immediately:

‘When I first met Sedick Salie, one of the things I liked most about him was his head. It’s sort of rugby-ball shaped—long, regal, with a defined chin. Sexy. Solid. Topped by a thick mane of brown hair, which is always nice if you’re the type who likes to pull on something when you’re in the middle of mind-blowing sex. Of course, the first rugby balls were made of pigs’ bladders, the leather stitched up to secure the bladder within. Bet you didn’t know that. Which also says everything you need to know about Sedick.’

I love it because it flings you right into the scene and sets the tone for this fast-paced, edgy, sardonic novel. How did you come up with such a powerful first paragraph?

Joy Watson: The prologue was written when I had already written the book. I knew that I would want to come back to it, because it would be the first time that the reader encounters Lolly. At this point, she is talking directly to the reader. I wanted it to have impact, to, in a sense, let the reader know everything they need to know about Lolly from the outset. By this point, Lolly was so real in my head and her voice was so clear, that the words flowed, quickly so. In some ways, it was the easiest bit to write.

Caution! The rest of this interview may contain spoilers. If you haven’t read The Other Me yet, run to your nearest bookstore or buy the ebook now.

You have been warned …

No turning back now!

The JRB: There’s a line on page 26 that really struck me. Lolly’s mother has just brought Uncle Jimmy home and while she’s passed out drunk on the bed, he turns his attention to the little girl lying on the floor: ‘There is an unspoken knowledge when we realise that we are in danger.’ Can you speak a bit more about this unspoken knowledge that lives inside the body?

Joy Watson: As women, we have internalised the fear of sexual violence so much that we inhabit our bodies and spaces with this inscription coded into us. We navigate our way through the world with it—in how we engage with others, in the choices that we make, such as whether we go out for a walk on a beautiful summer’s night or not, whether or not we turn away from someone who is looking at us in a way that sexualises and objectifies us. We also encounter this unspoken knowledge in ways that are less potentially violent—such as when we are sitting in a meeting and the men around the table are pretending to take us seriously, but they really don’t actually give damn, they’re only actually interested in what the other heteronormative men have to say. Imagine a world in which we did not have to carry this unspoken knowledge—a world where we could walk the streets viscerally with our bodies—whenever and however we want.

The JRB: Lolly is fiercely protective of her little brother, Lelo, taking on the role of mother rather than sister. This overbearing feeling of guilt and responsibility that older siblings experience is hugely relevant in South Africa, isn’t it?

Joy Watson: Indeed it is. There is a body of evidence that has documented child-headed households in South Africa. Even when children have parents or adults whom they live with, many are left alone to fend for themselves. Covid-19 brought this to the fore—the gaps in equity in our society. When the schools were closed and some businesses were operating, we heard of many parents who had to go to work and did not have the resources to make alternative arrangements for their children. Poverty is a huge structural driver of children being left to manage on their own—without expensive alarm systems, paid caregivers or huge fences around houses, all the things that are supposed to keep us safe.

The JRB: When Sue Higgins adopts Lolly, her new sister Jenny thoughtlessly tells her, ‘You’re white now.’ What happens to Lolly in that moment?

Joy Watson: In that moment, Lolly has to contend with all the ways in which she has tried to fit in and is never quite able to. She contends with the construction of her identity, as many of us do in this country. The book carries this as a central theme—how the markers of identity, whether it’s race, class, sexual orientation or mental health status—how these all intersect to write themselves into our stories and our ways of showing up in the world. In that moment, Jenny is the signifier of a society that places so much emphasis on pinning identity down in problematic, binary ways.

The JRB: Lolly does everything she can to fit into her new white family: ‘I lived in Newlands, went to St Cyprians, and spoke and looked like a different person.’ Do you think the ‘other Lolly’ is a manifestation of all the aspects of herself she had to cast aside—her voice, her rage—in order to become a daughter that Sue would love?

Joy Watson: Lolly is fundamentally unwell from a mental health perspective. Grappling with who and what she is and what society expects of her adds to her sense of not coping. She desperately wants to find ways of ‘getting things right,’ not realising that there is no formula or blueprint for this; it is not something that can be ‘managed.’ The Other Me emerges as an alter ego when she engages in a sense of psychic disassociation, when things become too much for her to bear. Ultimately, The Other Me takes over when she is in danger, when she feels unsafe.

The JRB: When Lolly meets Sedick, he assumes that she is white and she never corrects him. Why did she do that?

Joy Watson: I wanted to keep this true to how this would play itself out historically in our country. When people were reclassified as white in the past, they rarely went about talking about it. They recrafted themselves in their new identity and pretended that their past did not exist.

The JRB: On the day she marries Sedick, she realises that she’s marrying into exactly the kind of world she had left behind: ‘the smell of the flowers, the spicy aroma of the food, the loudness of it all, the homeliness … The memories I worked so hard at burying pushed their way to the surface’. Why go back to a life you’ve escaped?

Joy Watson: When Lolly first meets Sedick, he keeps her demons at bay. There’s a scene where Lolly smashes a soft drink can into a woman’s head and Sedick steps in to placate the woman and sooth Lolly. This is what he comes to represent to her—the person who keeps her calm, who keeps her safe. This is her primary need. She places her trust in the fact that Sedick will always protect her from harm. Until he doesn’t.

The JRB: Speaking of food, my mouth watered the entire time I was reading The Other Me! There’s so much food in this book, crayfish curry, kingklip, cottage pie, chicken and deep-fried potatoes, Cadbury’s chocolate, slow-roasted chicken rubbed with a masala, garlic and cumin paste … Pongrácz on tap. Is food your love language or Lolly’s?

Joy Watson: I so loved hearing this! Food is my love language and you caught me out here!

The JRB: The pivotal moment in the novel happens on page 108 when Lolly tells Sedick that she had a miscarriage. Everything goes awry after that and Sedick becomes obsessed with having a baby. What does this say about the undue societal pressure on women to reproduce?

Joy Watson: The issue of the autonomy that women have over their bodies has resurfaced in the global space since the Roe vs Wade conundrum in the US. While Lolly manages her pregnancy and the actions she takes in ways that lack integrity, I wanted to put this debate under the spotlight. What happens when society’s expectations do not allow women to make decisions about motherhood and control over their bodies and minds? There was definitely an agenda with this theme. The idea was to add a layer of complexity by making the situation not clear cut. Lolly deserves to be able to make her own decisions. However, she should not be manipulating others. Again, it’s one of the moments when I want to hand the situation to the reader and provoke the thinking, ‘What is going on here? Where are the moral lines? Might they be ambiguous?’

The JRB: Lolly’s husband is a huge Sedick without the ‘Se’. He chooses his family over her, verbally abuses her and eventually hits her—a nice guy in the beginning before showing his true colours. Why does she still want him even after he rejects her, going as far as to pretend she’s pregnant again?

Joy Watson: Sedick has bought into toxic notions of masculinity, as many men do. When a woman is in a toxic relationship, the journey to the end does not begin with, ‘And then she left him.’ I wanted to stay true to the lived realities of many women who love their partners, who are invested in a sense of a family unit, who find it difficult to walk away. The process of emotionally disengaging and seeing the monster that lurks beneath the façade of a human face, takes time. So Lolly goes back to him, as many women do. Until she does not, which is the point that we want to believe is possible when there is no other solution to addressing violence.

The JRB: Lolly’s definition of happiness as ‘something I feel when I am not worried about what the future holds’ is so relatable—the feeling of walking on a tightrope to avoid losing everything you’ve gained is so relevant. Do you think this anxiety is something we share as South Africans?

Joy Watson: Definitely so. While Lolly is manipulative and deceitful, she is also highly anxious. Given our past, we are certainly a highly anxious society. The Covid-19 pandemic has amplified this. We have all suffered loss in one way or another—whether it has been through death, the loss of a livelihood, the loss of being able to do the things we took for granted, the loss of the ability to reach out and touch someone, the loss of living without fear. In fact, the pandemic has entrenched the fact that we live in perpetual fear, with increased levels of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress syndrome and burn-out. We have had to dig deep within our reserves to address emotional and psychological wellness. For many, the sense of feeling trapped has unleashed a mental health crisis. We see this all around us—in the language people are using. In our conversations with each other, we are more likely to use words like ‘worry’, ‘afraid’ and ‘stress.’ We see the anxiety etched into people’s faces as they try to put on a brave face and manage as best they can in impossible circumstances.

The JRB: As her world collapses, Lolly becomes more and more like her mother: calling in sick to work, drinking too much, misbehaving in public. Was that a conscious decision on your part, or was it an inevitable evolution for the character?

Joy Watson: It was not a conscious decision, although there certainly are parallels. Lolly does not want to be her mother and it is a sad irony that in her unravelling, she becomes her in some ways.

The JRB: When the Other Lolly steps in to help everything goes from bad to worse. At the launch of the book at Book Circle Capital in Melville, you said that the ‘other Lolly’ might be a manifestation of mental illness. However, what I want to know is this: in a society that’s drenched in trauma, for whom ‘trauma is in the blood’ as Sindiwe Magona has pointed out, is Lolly’s separation of selves not a logical response?

Joy Watson: I most definitely agree. As a society, as a collective of people, we come from a very violent, troubled past. As a result of systemic inequity and many living beneath the breadline, we see the manifestation of trauma all around us. In grappling with the story of our past, trying to navigate the difficult terrain of the present (think state capture, loadshedding, widespread poverty) and in trying to reimagine our future, we have to look at our trauma full on in the face. But that’s hard and there are moments when the only way forward is to separate ourselves from the trauma.

The JRB: Despite its serious subject matters, The Other Me is a witty, compelling read. Qarnita Loxton called it ‘funny, dark, complex, heartbreaking’. How did you go about striking such a delicate balance to create the darkly beautiful?

Joy Watson: Given that some of the thematic areas of the book are substantive issues that we are grappling with as a society, I thought it would be very important to use humour as a literary device. It mattered to me that as dark as the book can be, that readers were laughing their heads off.

The JRB: Finally, in your Acknowledgements you wrote, ‘I can’t imagine that there might be more than five people out there who would want to read my work.’ I think we can agree that you were wrong there! Why do you think this story has captured readers so?

Joy Watson: It is so thrilling that this is the case. I have had many people reach out to me to say that Lolly was so very real to them, that she affected them deeply. I think that in some ways, Lolly makes us feel better about ourselves. We can reassure ourselves that no matter how bad things get, we are not Lolly! But I was also taken aback by how invested readers were in her as an unlikeable character. Notwithstanding her fault lines, readers seemed to have been cheering her on, wanting her to get it right, and they felt for her when she did not.

- Anna Stroud is a writer based in Johannesburg. Follow her on Twitter.