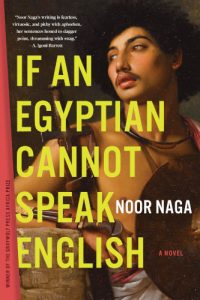

Shayera Dark reviews Noor Naga’s experimental debut novel If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English, winner of the Graywolf Press Africa Prize.

If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English

Noor Naga

Graywolf Press, 2022

It’s 2017, six years after the Arab Spring that ended Hosni Mubarak’s decades-long dictatorship, and Egypt is suffocating economically under the boot of a new ruler—so much so that some yearn for the recent past, when ‘the wheel of production didn’t stop once …’ What’s more, the wave of foreigners and diasporic Egyptians that flooded the country during the revolution, as ‘the global epicentre tipped in [Egypt’s] direction’, has since ebbed, along with dreams of redemption.

It is in this sociopolitical quagmire of regret and somnolence that Noor Naga’s experimental, homecoming novel If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English opens, tracing the observations of an acutely self-aware Egyptian-American woman (also named Noor) whose maiden trip to her parents’ homeland coughs up more questions, on the subjects of identity, authenticity and belonging, than answers.

Noor arrives from America to connect with her roots—‘two air quotes around the word roots’—although her shaven head, unusual fashion, and poor Arabic betray her as a foreigner, and immediately set up a boundary between her and those she regards as her people. However, her job as an English tutor at the British Council soon leads her to an upscale cafe, and a friendship with two middle-class Egyptians versed in local etiquette and Western culture. They provide her with cultural insights into her new environment without judging her identity, and for a while the duo constitute her regular companions, until an unnamed boy from the village of Shobrakheit enters the cafe—and her life.

So diametrically different are the two from each other that one expects their acquaintance to resist romance. He an occasionally homeless drug addict and unemployed photographer of the revolution; she a Columbia University graduate living in an apartment furnished with a doorman, airy balconies and furniture ‘living in denial of its geographic circumstance’. His English is nonexistent, and her Arabic painfully inadequate.

In chapters alternating between their points of view, their worlds clash in wry, revelatory and tragic ways. In one of his poetic text messages to Noor, in which he uses the word ‘fountain’, the boy from Shobrakheit assumes she doesn’t know the Arabic word and defines it. Noor finds the overwrought explanation condescending and replies in kind, in turn annoying him. Compounding their misunderstandings is the fact that in the language of her ancestors Noor feels constrained and estranged from herself, a situation she analyses as follows:

‘I am stupid in this Arabic, a blubbering toddler in his arms, defenselessly drooling all over his chest. Meanwhile he peers down at me from his height, his muscled tongue clicking, spitting.’

This push and pull intensifies as the tyranny of gender and class rears its head, in both overt and subdued forms. Watching Noor scrub her face with brown sugar, the boy from Shobrakheit remembers his impoverished mother trying to save grains of salt. Further, socialised to view women as potential damsels in distress, he feeds his male pride by protecting Noor from the city’s mean streets, where men rob, sexually harass and ogle women. Later, when Noor begins traversing the city alone, her independence irks him to the point of violence: ‘He senses that his usefulness is depleting,’ she muses, after he smashes a glass against a wall in her apartment. ‘Ever since he showed me how to buy vegetables from Bab El-Louk, I no longer need him to buy them with me.’

She theorises that his rage stems from the unrelenting deprivation that has marked his life but not hers, and goes as far as to accept his outburst without protest, if only to assuage the guilt she feels for missing the revolution and for her privileged upbringing—even though middle-class privileges are different for minority groups in white-dominated America. But beyond her intimate life, the glaring differences between New York and Cairo force Noor to interrogate certain American indulgences and obsessions: what really are microaggressions to limbless beggars and child hawkers, and is drinking alcohol in a country where it’s proscribed an act of rebellion or one of entitlement, if it doesn’t garner the hatred meted out to hijabis in America?

Meanwhile, the boy from Shobrakheit silently passes judgement on her Western ways. When she hands out money to children in a poor neighbourhood, he likens her to the German and Italian women who took photos of similar children without permission after handing them some spare change. ‘I always let these women empty their pockets without commenting, since there’s something retributive about the exchange, a kind of tourist tax,’ he muses. ‘And now with the American girl I catch myself doing the same thing …’

When their tenuous, undefined romance comes undone, both realise they have been shields for the other in their respective social spaces. He can’t access the posh restaurants or cafes that readily admit Noor, while she now has to endure having her identity questioned in the streets. But while the boy from Shobrakheit harbours feelings for her to an excessive degree, she doesn’t share his naivete about sex as an overture to love or marriage. And in that chasm arises the stalk of a deadly action.

Naga’s writing lends flair to a nuanced and intriguing narrative. The first third opens with koan riddles, the second incorporates footnotes, like an academic essay, to describe Egyptian culture, while the final third is written as a play, which shatters what assumptions the reader may have about whose perspective animates the story. Shimmering with philosophical depth, her writing is confident and deft, interrogating the tensions and contradictions around questions of identity: what constitutes it, how slight differences and large fragmentations arising from class and geography often complicate it, and why some may struggle to fully inhabit it. As Noor eventually realises about her place in Egypt:

‘I’m learning slowly that having money and the option to leave frays any claim I have to this place.’

- Shayera Dark is a writer whose work has appeared in publications that include LitHub, Harper’s Magazine, Al Jazeera, AFREADA, The Kalahari Review and CNN.