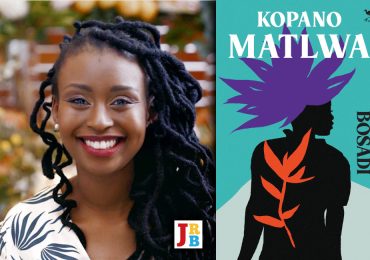

The JRB Editor Jennifer Malec talks to Nozuko Siyotula about her debut novel, Christopher.

Christopher

Nozuko Siyotula

Jacana Media, 2021

Jennifer Malec for The JRB: Your novel had a somewhat unusual journey to publication; the manuscript placed second runner-up in the Dinaane Debut Fiction Award, which I co-judged, in 2020, beating sixty other entries. Could you talk a little about this experience?

Nozuko Siyotula: I had been putting off entering the competition for years because I didn’t feel confident that I had a winning manuscript, and in the end I was right. Scatterlings [by the winner of the competition, Rešoketšwe Manenzhe] is a beautiful, well-thought-out book that deserved to win. What the competition did for me was to validate my ideas and style of writing, so when Jacana Media offered to publish the book I grew the wings that I didn’t have when I initially entered the competition. The book is a lot stronger conceptually because of the work that occurred after the competition.

The JRB: How did you find the editing process?

Nozuko Siyotula: I enjoyed it because it pushed me creatively. Attending to the issues in the text helps you as the writer to align with the story; if you really want to tell it, you find a way—it’s gruelling but it sharpens your art form. All writing, I have learnt, is rewriting. The millionth draft is closer to what you wanted to achieve and the published work could have been worked on one last time. I have made peace with that.

The JRB: Dinaane chair of judges Rehana Rossouw said of the book that it ‘skilfully made new meaning of the scars we bear and the future we imagine’. Does this comment resonate with you?

Nozuko Siyotula: Rehana Rossouw, I feel, understood the book in her bones. She understood exactly the sentiment I was striving for in writing Christopher, as only another writer can. Concepts are the foundation of a book and are not by design meant for entertainment. They require the reader to be engaged in the work but also reflective about their own lives, to test the strength of the ideas proposed, so if somebody understands your concepts and, even more than that, endorses them then I deem that success. I don’t expect readers to take from the book everything that I put into it, that’s not what reading is about. I will be just as happy if someone is entertained as if they are stimulated or provoked. I always want to assume the reader is highly intelligent and I, the writer, am fighting very hard to persuade them about the realities I am narrating, both of their truth but also of their significance to their understanding of life.

The JRB: In your Acknowledgements you write that you had wanted to write a novel since you were a teenager. How long has this book been percolating on your computer?

Nozuko Siyotula: I have been writing this book for years but doubt delayed the publication of it. I finished it in 2014 and then started ‘revising it’, which is a lie. I was afraid of rejection and I thought if it was rejected I would never try again. I committed to writing it after a notoriously difficult professor at law school gave me a distinction for my final year dissertation. So I decided to use the same framework I used in my dissertation, sans academic referencing, and applied that to my creative writing. After years of trying it different ways this method proved the best—reading non-fiction and historical texts for a year, drafting a road map, deciding on concepts, and outlining my intentions in writing the book, all these steps made it easy to refine the book over time and carve out what in the end was published.

The JRB: You also write that you wanted to ‘address how little I or my culture featured in the spaces I inhabited outside of my home, and where I formed ideas about my identity’. Why do you think fiction is important to this process?

Nozuko Siyotula: Until I attended university, I had always been a minority in the spaces where I spent most of my time, namely school—this in a country where the majority of people look like me. In my personal life, I also straddled worlds in which I identified mostly just in part with the situation. In recent years I have come to view that experience as a gift, but growing up it created deep consternation inside me about who I was. I have often felt guilty about my sympathies for various types of people and communities because of my proximity to them in one way or another. This will probably always be the lens through which I approach my fiction. Fiction allows for the space to bleed all these emotions out in a non-adversarial manner. The space for catharsis is amplified.

The JRB: Your novel seems to inhabit grey spaces: none of the characters is one thing only, they are victim and perpetrator, villain and hero, they challenge racial boundaries. Was this complexity important to you?

Nozuko Siyotula: It wasn’t intentional, I think everyone carries this duplicity. Nuance is my favourite thing about human beings, if you want to understand anybody fully you have to understand the many things they don’t reveal to you overtly, the essence of people is what makes them unique. The transition into democracy instantly created many overt duplicities in experience, which led me to wonder about the internal ones that are not easy to share because they are intimate, and also experiences that had not been formed because of political change. As a reader, too, complex characters live longer in my head because they make it tolerable to be ‘complicated’ in everyday life.

The JRB: The structure of the novel reinforces this complexity, as you take us inside the mind of each character one by one.

Nozuko Siyotula: Each character represents a time in our country; a generational perspective or an internal value or standard that they are pursuing, which the character believes will aid in lessening their suffering. These demarcations in the framing of each character made it easy to ‘get into their head’, so to speak. I also did this to imagine how much we as a society could achieve if we healed and placed the role of family at our centre. To my mind, the family is the most important political space.

The JRB: I think many people will be drawn to the women in this novel—and they are magnetic characters, strong, striking, bold—but I was equally fascinated by your male characters, the husbands and fathers, and the strong bonds they have with their children. Was this a version of masculinity you wanted to focus on?

Nozuko Siyotula: The January women could never exist if the men in their lives were ‘conventional’, because the world as we have known it for the past couple of centuries has been premised and prepared for the success of men. But my main concern was addressing that this type of successful man must always be overbearing and unkind. Men are men, they are shaped as much by oppressive systems as women are. I wanted to reimagine what equity could look like in an African setting. But I also wanted to celebrate the men in my life who have been January men in how they carry themselves in the face of the incredible devaluation of black life and experiences, which was once law in our country but persists in sentiment.

The JRB: The title of the novel is Christopher, but he’s kind of an absent presence for most of the book—we don’t really hear him speak until page 170. Why did you decide to name the novel after him?

Nozuko Siyotula: Christopher is a metaphor. He is in all the chapters, but I had to make him a person for the story to make sense conceptually—the Prologue of the book speaks to this as well as to how ‘Christopher’ exists in the past and present, which is how the book is written. All the characters are on a journey towards self and redemption. The patron saint of travellers is Saint Christopher. Redemption, in the Christian faith, is received through Christ who became flesh and died to redeem us of our sins. So essentially Christopher, the title, is a marriage of these two ideas and underlying themes in the book.

The JRB: ‘To know oneself is to be a part of a people.’ This statement of Vuyo’s seems to encapsulate the novel. Could you talk a little bit about what this means to Vuyo, and to you?

Nozuko Siyotula: I come from a big family and I was raised with community being prized. I understand myself always as part of a community and I believe that the chain of effort produced in communal spaces allows people to go further. How to manage the community so it’s always progressing and focused on things that matter is where the struggle lies. When Vuyo says this in the book, she says it as a revelation, because she has not believed it until that moment. I think that’s how we all come to take ownership and find the space from which we will make deposits into the efforts of the whole. I also think it’s the most sustainable way to live.

The JRB: After she moves from the village to the city, Romance says: ‘It felt like none of my business to be involved with whom the police did and didn’t shoot.’ Similarly, Mxolisi says ‘I didn’t become political until the night my father was murdered’: the novel emphasises how the personal becomes political.

Nozuko Siyotula: Most of the world is made up of ‘ordinary’ people and until the law or the state place limitations on your human experience, it is quite possible to live apart from politics. The most important politics in most of our lives will be that of those people who are a part of your life—friends, families, colleagues. I want to celebrate normal but I am equally invested in purpose, which doesn’t have to mean grandeur or excess but quality. Romance and Mxolisi returned, in the end, to a small-scale life when they realised that struggling for a ‘big cause’ was futile, it corroded their spirit and ultimately left them feeling lonely. They returned to build their community in order to go further and feel new things.

The JRB: At one point Romance says,

‘We heard all the time about what the police did to those who fought against them for liberation, but I worried about those whose struggles were not documented. Those who inherited the spirit of violence because of their proximity to it, who inhaled it like the fumes of a fire … men who become husbands and fathers even though they were broken things that hurt everything they touched.’

In a way, this novel is an attempt to document those very lives. Do you think literature can facilitate a kind of healing?

Nozuko Siyotula: On some level yes, I wrote the book because I believe that deeply. I am also alive to how a book can be a flattening of painful experiences that millions of people lived through, which cannot be imagined away creatively. I’m sensitive to both spectrums of thought, but I came of age in the time of the ‘rainbow nation’ and reconciliation, It was my staple diet, and I know there are many of us out there, so I think in the coming years I will have several peers who are similarly aligned who want to write fiction from this perspective. It would be useful to keep building a credible public discourse on the undocumented experiences of the ordinary in transitional and post-apartheid life. Photographers have been doing this forever in their art form. The ordinary tells us so much about what was actually political in a specific time. The centrality of traditional politics in people’s lives is often overstated.

The JRB: Finally, since writers are often great readers, we like to ask authors for book recommendations. What have you been reading recently that you think we should too?

Nozuko Siyotula: First, I have to confess that I read books when I am called to them so they may be really old in terms of the trend cycles. I am reading for my next creative project so it’s largely non-fiction books: Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance by Moya Bailey; The Cape Radicals by Crain Soudien; Louis Botha by Richard Steyn; Braving the Wilderness by Brené Brown; The State of Affairs by Esther Perel. Fiction, it’s The Last Gift by Abdulrazak Gurnah; Forbidden Colours by Yukio Mishima; Silent House by Orhan Pamuk and Sankofa by Chibundu Onuzo.

The JRB: That reading list has piqued my interest in your next book project. Could you tell us a little about what you’re working on?

Nozuko Siyotula: Since I am in the reading phase, all I have are scattered thoughts, but I am interested in the time before South Africa was a Union, cultural appropriation, the digital space, and intimate relationships that survive collective trauma. I don’t know which one will stick.

- Jennifer Malec is the Editor. Follow her on Twitter.