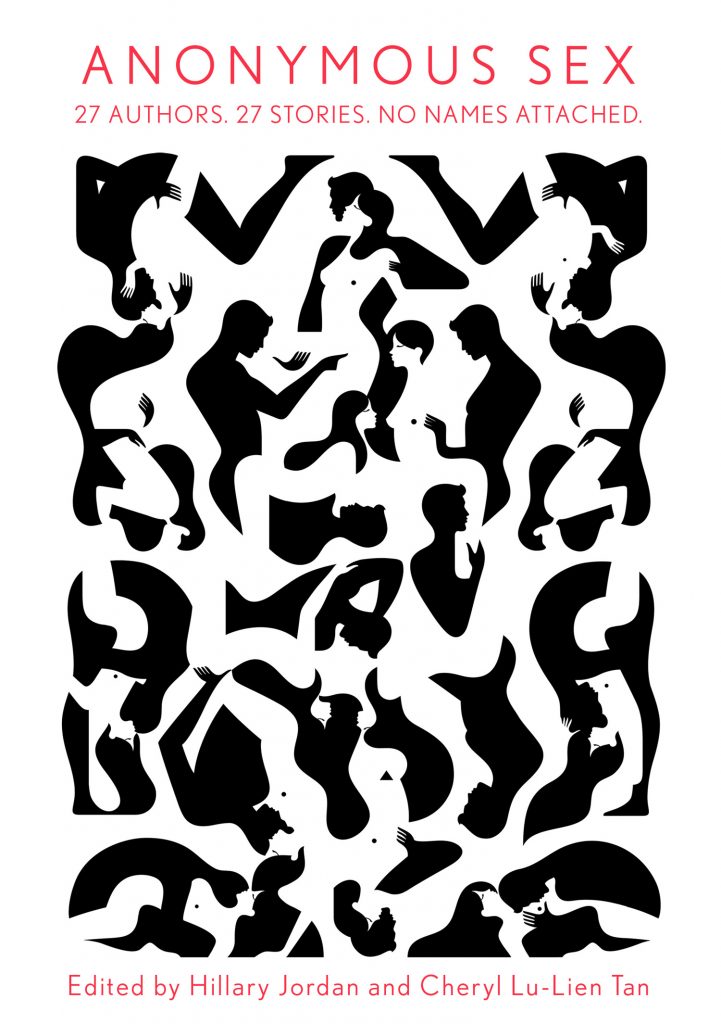

The JRB presents an excerpt from Anonymous Sex, a forthcoming anthology edited by Hillary Jordan and Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan.

Anonymous Sex

Edited by Hillary Jordan and

Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan

HarperCollins, 2022

Introduction by the editors

Some years ago, the two of us were sitting over dinner, talking about sex in literature—our enjoyment of stories about desire and sexuality, and what a treasure it is when an erotic story makes you see sex in a new way, as only great writing can.

How brilliant would it be, we thought, to create an anthology of fictional tales, penned by some of our finest writers, that would explore the diverse landscape of desire. But we decided it wouldn’t be enough just to have great contributors. We wanted to free them to write openly about what stirs them about sex. So we dreamt up a collection in which the authors’ names would be listed, but none of the stories would be attributed. And we’d call it Anonymous Sex.

To our knowledge, no one has ever published an anthology quite like this. Our international roster of contributors includes winners of the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, the Women’s Prize, the Carnegie Medal, and more. Among them are Booker Prize shortlister and judge Chigozie Obioma, South African novelist Tony Eprile and Zimbabwean journalist and memoirist Peter Godwin. Our contributors have written stories of queer sex, straight sex, revenge sex, sexual love, and sexual domination that are set all over the world—including two electrifying and moving tales in Kenya and Nigeria.

We hope you enjoy every eloquent, provocative, delicious word.

—Hillary Jordan and Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan, editors

~~~

How I Learned Prayer

by Anonymous

When I was a kid I went to church and Sunday school and Bible study every week. Had to memorize Scripture, learn every song, and know the steps necessary to dance on the head of the devil if the organ demanded. How to lift my hands and cry out for a savior I’m not sure I’ve ever actually believed in. And though the hallelujahs often felt a bit hollow to me, my mother, now gone on, would’ve been so proud to know I’ve finally learned to pray.

The first time was overwhelming, perhaps because I never knew prayer to feel like anything other than performance. But on a Sunday evening, Misha Ferndale, a theology student and tea drinker, taught me to pray some kind of truth.

I met her at work. Served her Lapsang, which came at my recommendation because she wanted a jolt but not too much. I’ve worked in a tea shop for a long time. Took the place over after my mother passed. I grew up there, a child peeking over the counter watching my mom steep pot after pot, listening to her preach about how with tea the flavor is often based on restraint and timing. Sermons on how much tea is the right amount, how to watch it change the color of water, how to time it to ward off its bitterness. I’ve also learned over the years that the people who come into tea shops aren’t the same as those who frequent coffee shops. Teahouses seem to be—and I don’t know this for a fact—but they seem to be more intimate. There’s no growling grinder, or gurgling milk frother. No slamming espresso cups, or nasty attitudes with complicated orders. It’s just about time. The people who hole up in teahouses typically come for the peace of it. There’s something, I don’t know, holy about it. They come with the intention of calmly waiting for water to be transformed coupled with the eagerness of that first sip. That, and studying. People serious about studying do so in tea joints.

‘You believe in heaven?’ I asked Misha one day, setting a single-serve teapot, cup, and saucer in front of her. She’d been coming in consistently for weeks, and I’d always pick her brain about what she was reading. Some days she’d go on about the history of matriarchal religions. Other times it was comparing and contrasting different prophets. Once we even spoke about what got her interested in theology in the first place, and her response was that it felt ungodly that her father never spared the rod. On this day, though, it was about the creation of the afterlife.

‘Like, as a destination?’

‘Yeah, I guess.’ I desperately wanted to believe there was such a place as heaven and that my mother was there sipping Assam with milk. But I had my doubts.

‘That depends,’ Misha said, sliding her pencil into the gutter of her theology book, closing it.

‘On what?’

She poured herself a cup, held it up to her face, and closed her eyes. She smelled it before slurping.

‘On whether or not one believes in prayer.’

‘You mean God?’

‘I mean prayer. God is too big. Too … everywhere. Prayer feels more graspable. More immediate, you know? And if prayer is real, we could all probably build heaven with it as long as you know heaven, according to what I’ve read, isn’t permanent.’

‘It’s not?’

‘From what I’m studying, it’s basically a teahouse where we’re the teapots. We’re the water being changed and prepared to comfort a new world.’ She picked up her book, flipped through the pages, then set it back down on the table. ‘But I don’t know anything. I mean, do any of us? I guess that’s why I’m saying prayer is an easier concept to give oneself over to.’

‘I’m telling you right now, if I get to whatever this new world is and I’m still making tea …’

‘I’d become religious, because it would then be confirmed that God don’t make mistakes.’ Misha hid her chuckle behind the lip of the cup, took another sip—on this day, rooibos—then let out an overexaggerated ahhh of satisfaction.

‘Okay, so … you believe in prayer?’ I asked, trying to hide the fact I was just as intrigued by Misha as I was the topic.

She smirked but didn’t answer. And she didn’t have to, be cause a week later she taught me that prayer could happen in all sorts of ways. Showed me that it could taste like decent Shiraz, branzino, or sumptuous chatter about oolong and hojicha, or unanswerable questions about whether or not sin is a thing, or if there is a praise that hasn’t been named. Questions that attached themselves to us, that were now part of this prayer that I was learning could walk back to her apartment. This prayer that could climb steps, leave shoes at the door. That could sound like the shish of a silk dress being pulled overhead after a second date I had to beg for because Misha was so busy with the business of earning a master’s. This prayer, like no prayer I’ve ever known, could sound like a woman telling me to genuflect.

‘Get on your knees,’ she said, almost as if she’d stolen language from my mouth. Her voice oscillated between whine and whisper. She’d already stripped me, already unbuckled and unbuttoned everything, my varnish vanishing in the dark. She’d pressed her lips to my chest, scraped her teeth across each of my shoulders, kissed my forehead, and finally my mouth.

‘Get on your knees,’ she repeated. ‘Please.’

The light from outside cut through the open blinds pulling stripes of brown from her silhouette, and I followed them down like rungs on a ladder.

When I was a kid, whenever it was time to pray my mother told me to close my eyes and press my palms together, but never said why. I figured maybe it was a symbol for those who were to be counted by the Lord in case he returned during eleven o’clock service. I also figured it was so I could imagine God, tiny and trapped between my hands. This way I could hold him close enough to hear me. Sometimes it made me feel like I was doing something. Most times it made me feel silly. But at this altar—the altar of Misha Ferndale—though my body was folded, nothing about me was meant to be closed in such a moment of reverence. There was nothing small to be captured in this hallowed space. Prayer was happening to me. Happening in me, around me. Prayer was standing in front of me, in panties.

Misha put her fingers in my hair, let them tangle in the thick of it, the perfume from earlier still on her wrists, wafting rose all around us. My hands on the backs of her knees, on the backs of her thighs, on her ass. My face resting on her stomach.

‘Salvation?’ I murmured while brushing my bottom lip across the skin just below her navel. It seemed like a random utterance, but it was an answer to a question she’d asked on the walk home. A question I was sure she’d forgotten.

To my surprise, she replied. ‘Maybe.’

Misha gently pressed on the crown of my head, asking me without asking me to lower myself.

I ran my nose along the lace elastic, dipping it down into the cotton, the only partition left dividing us. It was then and there I felt overcome with confession. Where I wanted to admit how I’ve never believed. How perhaps there is a penance for this. Atonement. I pulled her closer and pushed my face into the fabric, breathing into the soft tuft protecting the small space the same size my hands used to make when I tried praying as a child. I was now certain God was there. Certain God was close enough to hear me.

‘Sanctuary?’ I asked, trying again.

‘Maybe.’ She gasped, squirmed in her skin, slipped her thumbs into the waistband of her panties, and tried to push them down. But I stopped her. Moved her hands because it wasn’t time. Not yet. I glanced up and was stunned by the streak of light across her breasts, another across her clavicle, another across her mouth. I wondered if I looked as beautiful to her. I wondered what it was like to see me halved and still whole.

‘How about ceremony?’ I asked between kissing her creases and corners, stroking the hinges of her.

She couldn’t get the answer out before it became air. She tried to say it again but it caught in her throat. Her hands returned to my head, as did her weight. She wanted me to sub merge, knowing our prayer contained baptism, patient steeping. She knew there was an anointing to come. A blessing she had for me, and I for her. We were to be sacrament, Communion, both ready to sip and be sipped from.

Then I did what she wanted to do—what she’d tried—and slipped my fingers between waist and waistband, began to slide them down. A shiver worked its way through her body, a spirit caught, a dance trapped, and she now raised her arms in a praise that hadn’t been named.

‘Ceremony?’ I repeated, steeping my fingers deeper into the holy water.

And after a moment, she managed in what seemed like a final breath to say twice more, ‘Maybe. Maybe.’

And as I prepared to meet my maker, to be introduced to a fleeting heaven, to sing a new hymn and whisper amen to a savior I’m now convinced is real, I replied, ‘Oh, God, tell me, then, what is another name for rapture?’

~~~

Anonymous Sex will be published in South Africa in February 2022.