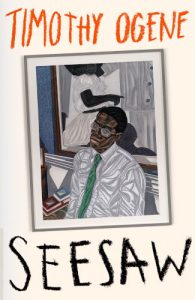

The JRB presents an excerpt from Seesaw by Timothy Ogene.

Seesaw

Timothy Ogene

Swift Press, 2021

Read the excerpt:

My second and humiliating outburst in Boston involved Kabumba, who had taken it upon himself to chastise me for not ‘producing work’. I could tell that he was truly disappointed. He was the sort of writer who saw himself as the carrier of his continent’s honour, the defender of ‘his people’ against all forms of misconceptions. His capacity to simultaneously charm his audience while defending his dear continent was astonishing. If he saw Africa as his to protect, insisting on the need for ‘African writers’ to produce ‘authentic’ stories, Sara was in charge of the post-colonial world, calling on her intimidating repertoire of theoretical insights to ‘contextualise’ the ‘legacies of colonial encounters and ruptures’. She ‘situated’ my ‘post-colonial refusal to write in the long histories of’ something or other that I quickly forgot because it gave me an instant migraine. Deepak, the Nepali writer, was indifferent and did not take it upon himself to drag me for not producing work. Claudia González did not care either. She thought I was charming, that I carried the aura of writers who became famous for the ‘precise fact’ that they stopped writing or wrote so infrequently that every word was eagerly awaited. She called me an ‘artist of silence’, a writer ‘dwelling in a space of silence’, like ‘Rimbaud who refused to write’, and suggested I read Bartleby & Co by Enrique Vila-Matas. She made these remarks while we were sitting outside Café Pamplona in Harvard Square, with Deepak, Kabumba and Sara. We were months into our residency and they’d each had two public readings, submitted three pieces of work, and led several workshops for undergraduates. I hadn’t done any, providing Kabumba with a generous opportunity to be disappointed in his fellow African writer. He and I reported to the same supervisor, one Professor of the Practice of Prose and author of Feathers of Conscience (Honeysuckle Press, 1980), a one-hit wonder that secured the writer several fellowships to travel through Europe in the late eighties and early nineties. I had a feeling the Professor of the Practice of Prose, or PoPoP, and Kabumba discussed me behind my back. I was sure they did, in fact, since Kabumba once asked, ‘Frank, is it true you haven’t been submitting work?’, following this with another question: ‘Why’s your name absent from the seminar roster? I thought we were all supposed to give talks?’ After that he stopped talking to me, except in moments when he saw an opportunity to make sweeping pronouncements intended to put me in my place while defending Africanness. For example, his response to Claudia González’s remark that day at Café Pamplona was a direct attack: ‘A writer writes, and for us African writers we must write to correct centuries of colonial misrepresentations. It is our duty to confront narrow-minded accounts of Africa. We must make it clear that Africa is not a country.’ I tried to reply but he fired on. ‘Until the lion learns to speak, the tale will always be the hunter’s.’ Deepak was nodding at this remark while texting on his phone. I thought hard about what he was saying. I contemplated an answer but dismissed the whole thing. Instead I looked straight ahead and kept my eyes on a group of Chinese tourists taking selfies in front of the Church of St Paul.

That same week, I was standing outside Café Roma on Pratt Street sharing a joint with a homeless man I’d come to know when I saw Kabumba with a group of other Africans holding up placards protesting the arrest of some journalist slash activist slash NGO worker in faraway Angola. I’ll never forget how they looked at me, shook their heads and marched on. And with them that day was some Nigerian chap I had met at a conference on ‘Growth and Opportunities in Africa’, organised by William Blake in collaboration with the Institute of African Studies at nearby Roxbury University. The young man had delivered a paper on ‘Nigeria and Its Centrality to Africa’s Rising Markets’ and his presentation was so fantastic that I applauded at the end. He’d pointed out the ‘strategic location of Nigeria on the map of Africa’, how Nigeria was ‘positioned as a trigger’ on the map. ‘See,’ he said, pointing at a blank map of Africa with the spot for Nigeria highlighted in green, ‘see how Africa is shaped as a pistol pointing downwards?’ And indeed, we all saw that, and quickly saw how Nigeria was in fact the ‘trigger’ of that pistol. ‘Any growth in Nigeria,’ he said, shooting his audience a very African smile, ‘triggers growth around the continent.’ I found myself itching to chat with him afterwards. There he was with a group of fellow presenters, Nigerian Ivy Leaguers. I approached them, aware that I reeked of tobacco, my forest of a beard contrasting with their clean-shaven faces. I was also aware that I wasn’t schooled in the lingo of Africans educated in Europe and America, their savvy cosmopolitanspeak. I just wanted to tell the chap what I thought of his presentation, that I liked the metaphor, that it must have made a lot of sense to Americans who truly knew about guns. But as I approached, their body language made it clear that they didn’t want to be associated with this unkempt creature. It was there on their faces, on their drawn lips. Wounded, I shelved my compliment. I broke into their circle, stretched out my hand to the chap for a handshake, and attacked him with the first thing that came to my mind. ‘That was a nice metaphor,’ I said, ‘but I wonder if a penis would have made a better metaphor. You see, Africa does look like a large penis pointing downwards, with South Africa as the very tip, and West Africa as the scrotum, which puts Nigeria somewhere at the intersection of the barrel and the nut sack.’ I left them to digest my comment, grinning as I grabbed a handful of mints from a tray near the exit.

It was on the walk back to campus, after seeing Kabumba and his fellow protesters, that I saw an old but still working typewriter left on the side of the street. I picked it up and called it Dos Passos. I wasn’t sure why I named it after that American writer. Maybe it was something the homeless man had said about wanting to be somewhere in the world where he could actually write the ‘United States of America’ on a ‘postcard’ and send it home, which made me think of Dos Passos and the line about ‘USA’ as ‘the letters at the end of an address when you are away from home’. And maybe it was the weed, a strain my homeless buddy said would ‘get me going’, or maybe I was subconsciously trying to prove Kabumba wrong, but I saw in that old typewriter my opportunity to break free from my anxieties and write.

I carried it off to my room and the next day I bought the right paper and ribbon and got a big bottle of cheap whisky. And that night, as Glenn Miller played on Spotify, I recreated a scene from a black and white movie I once saw about a reclusive writer in New York struggling to complete the novel that would later make him famous. It was the sixties again and I was living that writer’s life. I could see him hunched over his desk, his drink to one side and his typewriter in front of him.

I cranked the music up and drank and typed away and dreamed.

~~~

- Timothy Ogene was raised in the outskirts of Port Harcourt in southern Nigeria. He has since lived in Liberia, the UK and the US, where he is a Lecturer in African literary and cultural studies at Harvard. Seesaw is his second novel.

~~~

Publisher information

‘A very funny, intelligent, deliberately and engagingly resistant, and moving piece of writing.’—Amit Chaudhuri

A ‘recovering writer’—his first novel having been littered with typos and selling only fifty copies—Frank Jasper is plucked from obscurity in Port Jumbo in Nigeria by Mrs Kirkpatrick, a white woman and wife of an American professor, to attend the prestigious William Blake Program for Emerging Writers in Boston.

Once there, however, it becomes painfully clear that he and the other Fellows are expected to meet certain obligations as representatives of their ‘cultures.’ His colleagues, veterans of residencies in Europe and America, know how to play up to the stereotypes expected of them, but Frank isn’t interested in being the African Writer at William Blake—any anyway, there is another Fellow, Barongo Akello Kabumba, who happily fills that role.

Eventually expelled from the fellowship for ‘non-performance’ and ‘non-participation,’ Frank Jasper sets off on trip to visit his father’s college friend in Nebraska—where he learns not only surprising truths about his father, but also how to parlay his experiences into a lucrative new career once he returns to Nigeria: as a commentator on American life …

Seesaw is an energetic comedy of cultural dislocation—and in its humour, intelligence and piety-pricking, it is a refreshing and hugely enjoyable act of literary rebellion.