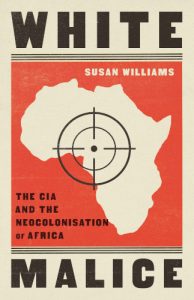

The JRB presents an excerpt from Susan Williams’s new book White Malice: The CIA and the Neocolonisation of Africa.

White Malice: The CIA and the Neocolonisation of Africa

Susan Williams

Hurst Publishers, 2021

Read the excerpt:

Ezekiel Mphahlele’s literary and academic career went from strength to strength. In 1959, the year after the AAPC in Accra, he published a powerful memoir of his experience of apartheid, Down Second Avenue. In 1966–1968 he was sponsored by the Farfield Foundation to study for a PhD in creative writing at the University of Denver. His thesis, a novel titled The Wanderers, won first prize for the best African novel in a competition organised by African Arts magazine at the University of California, Los Angeles. When the source of the funding of the CCF and the Farfield Foundation was revealed in the mid-1960s, Mphahlele’s response was one of anger. In a letter to the editor of Transition, he gave what he called ‘my side of the story’:

Yes, the CIA stinks. … We were had. But in Africa, we have done nothing with the knowledge that the money came from the CIA; nor have we done anything we would not have done if the money had come from elsewhere. …

We must naturally bite our lips in indignation when we learn the CIA has been financing our projects. But it is dishonest to pretend that the value of what has been thus achieved is morally tainted. …

We attend a number of conferences abroad without ever asking ourselves the ulcer-promoting question where the organisers got the money from. We sit in hotel bars and get boozed up between conference sessions without asking ourselves such questions. … And it would be stupid to ask such questions, as long as one is satisfied that one is not compromising one’s intellectual and moral integrity.

Then he insisted, ‘I firmly believe that those who have, have the moral duty to give to those who haven’t. … I know what poverty is. The rich must support worthy causes. It is a fiction to think that the poor must necessarily lose their self-pride when they are being helped’.

Mphahlele continued his argument in Afrika My Music: ‘A gong went. Someone blew the whistle. … Several of our accusers should also remember, I concluded, the conferences they had attended abroad and locally, where they were accommodated in posh hotels, and dined and wined on money which, for all they knew, might have come from a contaminated source’.

Wole Soyinka was outraged by the discovery. ‘Nothing, virtually no project, no cultural initiative’, he noted in fury, ‘was left unbrushed by the CIA reptilian coils.’ One such project, he complained bitterly, was the first Congress of African Writers and Intellectuals, which was held at the University of Makerere in June 1962 and was sponsored by the Congress for Cultural Freedom. Organised by Mphahlele, it brought together many of the best-known writers at the time from Africa and the African diaspora, including Soyinka, Ngugi wa Thiong’o (then using the name James Ngugi) and Chinua Achebe. Writers for Drum came, too, including the South Africans Lewis Nkosi, Nat Nakasa and Bloke Modisane, and the Ghanaian Cameron Duodu.

Yet more conferences in Africa were sponsored by the Congress for Cultural Freedom and other CIA pass-throughs, such as a seminar on French African Literature at the University of Dakar in 1963 and the Freetown Conference of African Literature and the University Curriculum held at Fourah Bay College, also in 1963. The papers given at these conferences were edited by Gerald Moore and published as a book by the CCF.

‘Not one of us’, lamented Soyinka about his fellow African intellectuals, ‘had the slightest suspicion that a Farfield Foundation of America, which so lavishly expended its resources on the continent’s postcolonial intellectual thought and creativity, was a front for the American CIA!’

Nevertheless, the reputations of some of these writers were affected by the revelations, because it was assumed they had been witting. They were yet more casualties of the injustice inflicted by the masquerades of the CIA.

* * *

Through the CIA’s layered and extensive network of connections, writer Lewis Nkosi met John ‘Jack’ Thompson, the CIA-salaried executive director of the Farfield Foundation. Encouraged and aided by Thompson, Nkosi obtained funding for a year’s fellowship at Harvard. ‘One pearly-white evening in January of 1961’, wrote Nkosi in New African, ‘we were winging down over New York. Jack Thompson, the executive director of Farfield Foundation, and the man most instrumental for my coming out to America, was waiting on the balcony of the airport lobby. Jack Thompson and I had our first drink at the airport bar. The last time we had had a drink together was at Western Native Township on one incredibly hot night’. As Nkosi shows, Farfield hospitality was generous. Nathaniel ‘Nat’ Nakasa was also brought to Harvard by Jack Thompson in 1965, on a fellowship funded by the Farfield Foundation. He had already been funded by Farfield to establish a literary magazine called The Classic, which featured writers such as Mphahlele and Can Themba. Soon after his arrival in the US, he became the subject of surveillance by South African intelligence and the FBI.

On one of his student assignments, he stayed at the Hotel Theresa in Harlem. When a Harlem shopkeeper showed him a photo of the burned body of a lynching victim surrounded by a crowd of grinning whites, he was shocked. ‘I had never known such personal fear, not even in South Africa’, he told The Harvard Crimson.

One night, Jack Thompson invited Nakasa to spend the night at his Central Park West apartment. The next morning, the twenty-eight-year-old writer was found dead on the street, seven stories below Thompson’s apartment. The death was reported as a suicide, and it was noted that Nakasa had been depressed at the time. However, many questions have been asked about what happened that night, and members of his family are convinced it was not a suicide. The fact that he had spent the night in the apartment of a CIA official suggests that any sinister explanation for the death would point to the agency, but it is unclear why the CIA would wish him dead. The apartheid government of South Africa had identified Nakasa as a communist, but this had not prevented Thompson from facilitating his move to the US. One can speculate that Nakasa had discovered the source of his financial support and was planning to expose it.

The nature of Nakasa’s death recalls the method of killing advocated in the 1950s CIA manual referred to in Chapter 20 of this book: ‘the contrived accident’, the most efficient of which was ‘a fall of 75 feet or more onto a hard surface. Elevator shafts, stairwells, unscreened windows and bridges will serve’. Grabbing the victim by the ankles and ‘tipping the subject over the edge’ was recommended.

Similar questions were asked about the death of Frank Olson, an American scientist working in the CIA’s secret biological-warfare laboratories at Fort Detrick who fell from the thirteenth-floor window of a hotel in New York in 1953. The death was ruled a suicide, and he was labelled as depressed. However it emerged in 1975 that his drink had been covertly laced with LSD at the direction of Dr Sidney Gottlieb, the head of the Technical Services Division at the CIA, who ran the MK Ultra programme—the same biochemist who went to the Congo to deliver poison to Larry Devlin to kill Patrice Lumumba.

There are similarities between the tragic deaths of Frank Olson, of Abraham Feller, the chief legal counsel of the UN, in 1952, and of Nat Nakasa: all three were described officially as suicides; all three men were described as depressed; and all three fell from the balconies of New York high-rises.

* * *

In the late 1970s, Mphahlele changed his first name from Ezekiel to Es’kia. In 1990, he and Alf Kumalo cowrote Mandela: Echoes of an Era, which gives an account of Nelson Mandela’s life, intertwined with a chronicle of forty-one years of the African National Congress. Four years later, in South Africa’s first free elections, the ANC was voted into power and Mandela became president. Mphahlele returned home, and Mandela awarded him the Order of the Southern Cross, which at the time was the highest form of recognition in South Africa.

The lives of both Nelson Mandela and Es’kia Mphahlele were profoundly influenced by the CIA, but in markedly different ways. Mandela was a target of the agency’s surveillance and covert operations, which led directly to his arrest in 1962, after CIA agent Donald Rickard gave the apartheid government information about Mandela’s whereabouts and his disguise. For Mphahlele, the agency was a source of generous funding, international travel and contacts, and facilitated the publishing and positive reception of his work. It was also a source of anguish after the revelations about the role of the CIA in the Congress for Cultural Freedom.

Together, their histories illustrate the spider’s web of the CIA’s covert interference in Africa. It was a vast and spreading web, glued by money, violence and betrayal, collaboration with racist governments, propaganda projects and the hijacking of sincere artistic aspiration in a battle for hearts and minds. Covert action of any sort, said Frank Church, the Idaho Democrat who chaired the 1975 Senate Select Committee investigation into the abuses of the CIA, was nothing more than ‘a semantic disguise for murder, coercion, blackmail, bribery, the spreading of lies, whatever is deemed useful to bending other countries to our will’.

~~~

- Dr Susan Williams is a senior research fellow in the School of Advanced Study, University of London. Her books include Who Killed Hammarskjöld?, which in 2015 triggered a new, ongoing UN investigation into the death of the UN Secretary-General; Spies in the Congo, which spotlights the link between US espionage in the Congo and the atomic bombs dropped on Japan in 1945; Colour Bar, the story of Botswana’s founding president, which was made into the major 2016 film A United Kingdom; and The People’s King, which presents an original perspective on the abdication of Edward VIII and his marriage to Wallis Simpson.

Publisher information

The shocking, untold story of how African independence was strangled at birth by America’s systematic interference.

Accra, 1958. Africa’s liberation leaders have gathered for a conference, full of strength, purpose and vision. Newly independent Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah and Congo’s Patrice Lumumba strike up a close partnership. Everything seems possible. But, within a few years, both men will have been targeted by the CIA, and their dream of true African autonomy undermined.

The United States, watching the Europeans withdraw from Africa, was determined to take control. Pan-Africanism was inspiring African Americans fighting for civil rights; the threat of Soviet influence over new African governments loomed; and the idea of an atomic reactor in black hands was unacceptable. The conclusion was simple: the US had to ‘recapture’ Africa, in the shadows, by any means necessary.

Renowned historian Susan Williams dives into the archives, revealing new, shocking details of America’s covert programme in Africa. The CIA crawled over the continent, poisoning the hopes of 1958 with secret agents and informants; surreptitious UN lobbying; cultural infiltration and bribery; assassinations and coups. As the colonisers moved out, the Americans swept in—with bitter consequences that reverberate in Africa to this day.