Fernweh, Teju Cole’s latest photobook, feels like a palliative moment amid the uncertainty, loss and raw grief of the pandemic, writes Sindi-Leigh McBride.

Fernweh

Teju Cole

Mack, 2020

Fernweh, the title of Teju Cole’s most recent photobook, describes a longing for faraway places. An antonym of the German word heimweh (homesickness), it literally translates as ‘far-woe’. The book was published just before the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, the result of half a dozen trips to Switzerland over a period of five years.

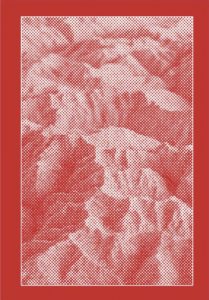

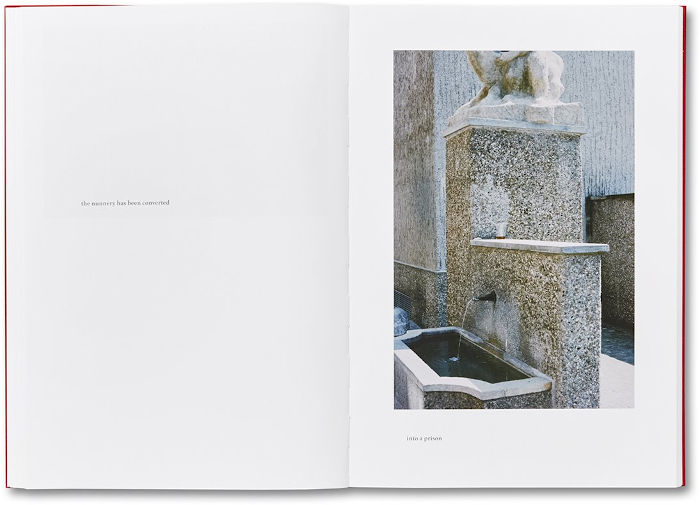

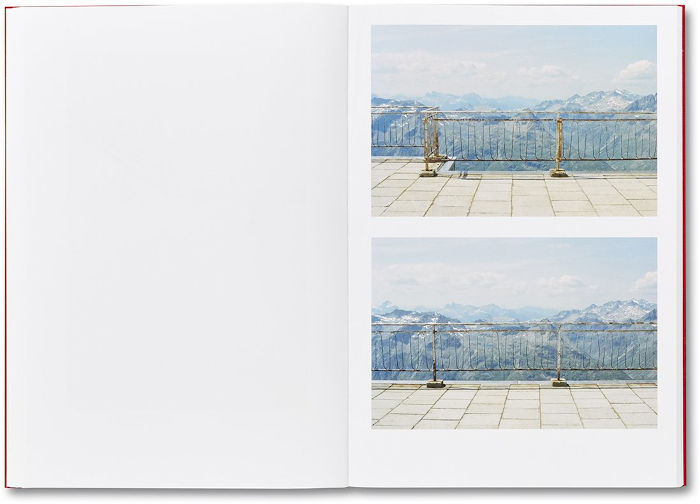

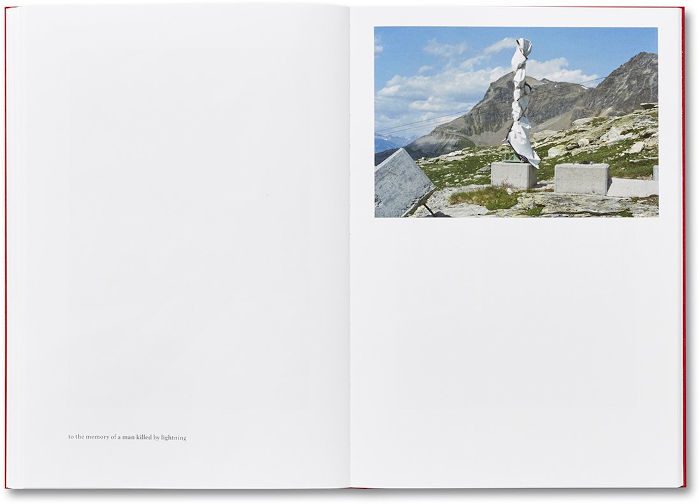

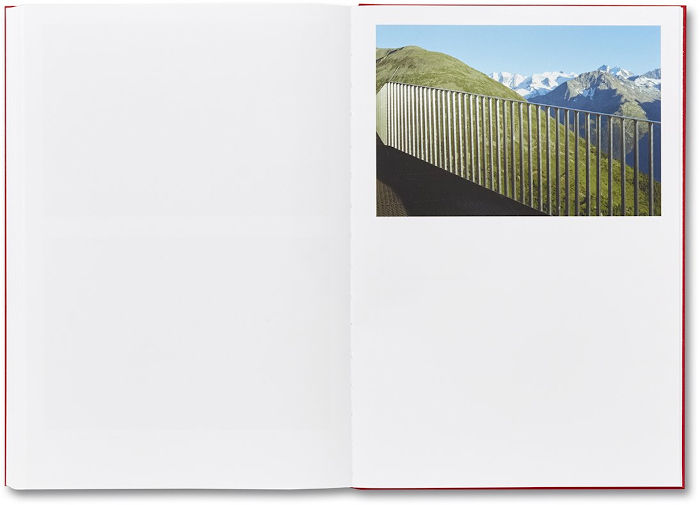

I have been revisiting Fernweh for a few months now and the technical crispness of the book is worth savouring at every point, from the brightly beautiful red silkscreened cloth cover to the impeccable print quality. The photographs are pensively composed and collated, with a dainty dusting of text between the images, like snowdrops between seasons. In a recent essay, ‘In Praise of the Photobook’, Cole describes the multidimensional joy of photobooks-done-well, how ‘the tactile and sensory trace’ of the photographer remains with the reader as ‘the memory of the work, once encountered, becomes idiosyncratically specific.’ There is a feeling of curt excellence to this book, uncannily similar to the feeling I get from Switzerland. I have lived here for nearly two years and often find myself resentfully impressed. The apparent stability can be galling in comparison to South Africa’s relative turbulence.

Fernweh features few people. Instead, you get the sense that Cole has been lurking around the country sniffing stories out of scenes, sussing out the potential of a landscape long assumed barren of photographic lifeblood. In an interview on the podcast Between the Covers, he observes that Switzerland is not very high on the list of places that people find interesting—‘relegated to that place that people’s grandparents went for their honeymoon … it’s rich, and it’s well-organised, and boring’—despite the material fact of extreme beauty that neither exhausts nor bores him. And so, he approached this project asking, ‘Why is it decided ahead of time that Switzerland is not an interesting subject? What forms of interest are available?’

Almost as interesting as this inquiry is his own self-awareness while pursuing it:

‘I know what it’s like to be a Black person in Europe, at least a travelling Black person, if not one who’s living there and employed there. Switzerland has its falsehoods, but the rest of Europe has monumental and very distressing falsehoods … When I go for a hike in the Alps in Switzerland, I’m just a guy going for a hike in the Alps. It’s a monumental relief. The places where a Black person can go in this world—that are majority white places and yet not exhaustingly oppressive—are few, and that was part of what this book was quietly doing. It’s saying, I speak only for myself, but this is one place where I can breathe.’

When I repeated his words to Black people and people of colour living in Switzerland, they would either laugh bitterly or emphatically agree, depending on how bad their experiences had been elsewhere. Woke white people would either be confused or flabbergasted. Of course, Cole is super successful, so his experience of this country is classed. But that said, I understand why a Black man who has lived in America for a long time would long for sojourns in staid Switzerland. In ‘Black Body: Rereading James Baldwin’s “Stranger in the Village”’, Cole follows Baldwin’s footsteps to Leukerbad, the Alpine town he visited in the nineteen-fifties, a town that might not ever have seen a Black person before Baldwin arrived. For both Baldwin and Cole, the experience offers a vantage point on white supremacy, how it functioned and thrived:

If Leukerbad was his mountain pulpit, the United States was his audience. The remote village gave him a sharper view of what things looked like back home. He was a stranger in Leukerbad, Baldwin wrote, but there was no possibility for Blacks to be strangers in the United States, nor for whites to achieve the fantasy of an all-white America purged of Blacks. This fantasy about the disposability of Black life is a constant in American history. It takes a while to understand that this disposability continues. It takes whites a while to understand it; it takes non-Black people of color a while to understand it; and it takes some Blacks, whether they’ve always lived in the US or are latecomers like myself, weaned elsewhere on other struggles, a while to understand it. American racism has many moving parts, and has had enough centuries in which to evolve an impressive camouflage. It can hoard its malice in great stillness for a long time, all the while pretending to look the other way. Like misogyny, it is atmospheric. You don’t see it at first. But understanding comes.

My own experience here deepens my understanding of racism as atmospheric, and the subtle ways in which Switzerland has exported its own particularly disarming brand, which oscillates between venomously polite prejudice and discrimination denialism. I pay close attention to it, it helps me to rethink apartheid, and I start to understand what Baldwin meant when he wrote that ‘people are trapped in history, and history is trapped in them’.

In Fernweh, Cole writes,

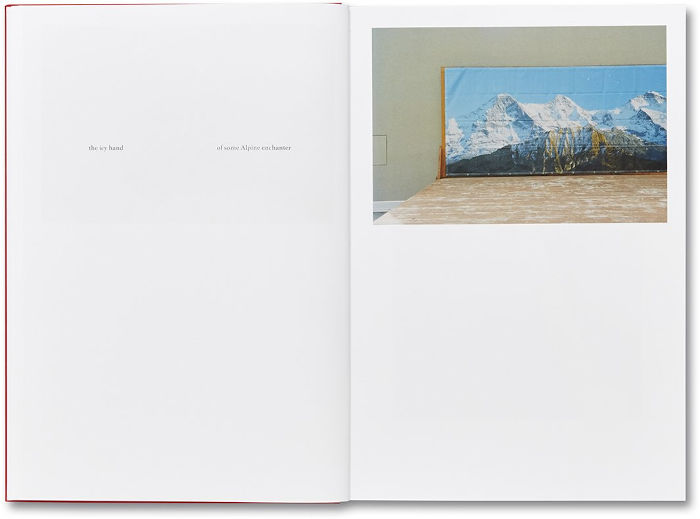

All closely observed worlds seem to be thinking themselves, remembering themselves, but few places are as close to their perfected postcard image as Switzerland is. This, after all, is one of the key places where nineteenth century travel photography was developed. It is one of the cradles of the camera mediated sublime. And so, to photograph Switzerland is to rephotograph it.

I shared the book with a Swiss friend who works in nature conservation and almost immediately he remarked that many of the landscape photographs feature some kind of artificial interruption to typical alpine imagery. The images might feature few faces, but Cole captures well just how loudly the presence of people has been inscribed onto the land. Walking along a picturesque vista, you never get the sense of any kind of environmental degradation, because the country is so pristinely presented, but at the same time the combination of excellent infrastructure and eerie absence of wild animals often makes being outdoors feel surreal, like a theme-park version of nature.

But this is perhaps what makes Fernweh so compelling: despite being just as pristine as their content and setting, somehow the photographs exquisitely capture the confusion of the place. Sunil Shah puts it well: the ‘mountain vistas are both seen and reflected everywhere, in tourist information, in advertising, in product branding’ but ‘somewhat muted by their hypervisibility’, which Cole does well to both draw attention to and overlook, ‘turning towards the non-spaces of place and in composing a full frame, flattening depth.’

Granta describes the impression that Fernweh offers of the country: ‘The photobook is beautiful but it is not in any simple sense a love letter, there is an ambivalence’, to which Cole replied that he likes Switzerland ‘in the sense of never wanting to belong to it’. That resonated with me, belonging as I do both in and to Johannesburg. I am incredulous at how lofty a goal belonging is here. Many strive for it, lured by the material luxury of Swiss life, despite the high barriers to access and acceptance.

I recently learnt that the German term heimat (roughly translated as ‘homeland’) holds great weight here. An institutionalised example of this is how Swiss identity documents include the place of origin (Heimatort in German, Hieu d’origine in French or Luogo d’origine in Italian), a communal citizenship that is not be confused with the place of birth or place of residence, although these locations may be identical depending on the person’s circumstances. Uniquely in the world (except for Japan and Sweden), Swiss passports and driving licenses all show this communal citizenship, in essence an inherited belonging. In addition to the usual requirements (many years and lots of money), aspirant Swiss citizens must first be approved by the local commune (municipality) who determine whether an applicant has successfully integrated into Swiss society and whether they are familiar with the Swiss way of life. This first application is followed by two more applications at the cantonal (provincial) and federal government levels.

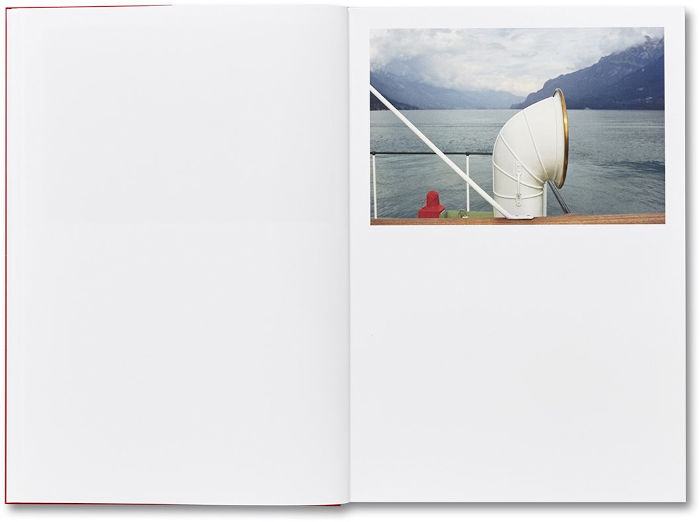

This could be dismissed as standard first-world exclusivity but for the high number of foreign residents in Switzerland—roughly a quarter of the population. This means a two-tier system, with foreign residents effectively living as second-class citizens: paying compulsory taxes, pension and unemployment insurance contributions, and contributing to the domestic economy, but with zero political rights. This chimera of political progressiveness mirrors much. For many, Switzerland exemplifies a historic example of functional democracy, but this democracy has only existed since 1971, when men first allowed women to vote. The economy is successful because of global trade, but the country affects distance from the rest of the world. Diplomatically neutral, Switzerland exported weapons worth half a billion Swiss francs (R7 billion) in six months, in the thick of the pandemic. This isn’t the content that Cole addresses in his photographs, but it is the setting of his ‘many afternoons of drift and solitude, in cities, in villages, on ferries, on hiking paths, in the landscape, and in the mountains.’

I consumed these photographs very differently to how he created them: at the dinner table at home, surrounded by friends filling my ears with the lilting burr of Swiss German swirling around crisp standard German, neither of which I understand. I don’t speak any of the four national languages (German, French, Italian and Romansch) because somehow it hasn’t been necessary to learn them. That said, I have taken pleasure in picking up choice words here and there. Perusing Fernweh in this way, I recalled a fragment from Cole’s Blind Spot, accompanying a photo of Lugano:

I don’t want to move to Switzerland. Quite the contrary, I like to visit Switzerland. When I am not there, I long for it, but what I long for is the feeling of being an outsider there and, soon after, the feeling of leaving again so I can long for it.

I have been very fortunate to land with my bum in the butter in Basel, where my community is as kind and generous as the cheese and chocolate are abundant. It is not like this for everyone, but Switzerland has proven to be a safe place for me to feel like an outsider and, like Cole, I revel in this feeling. Peopled though my experience may be, Fernweh made me realise that Switzerland has come to feel like my very own Walden, and my solitude here is rippled but not ruffled. Amid the angst and ache of uncertainty, great loss and raw grief of the pandemic, Fernweh is a remarkable work during a societal eclipse. It feels like a quiet moment, a palliative portal to peace. In a pre-pandemic interview with the podcast On Being, Cole discussed his attraction, in all the arts—

to those places where something has been quietened, where concentration has been established. I think one of the great artistic questions for any practitioner of art is, how do you help other people concentrate on a moment?

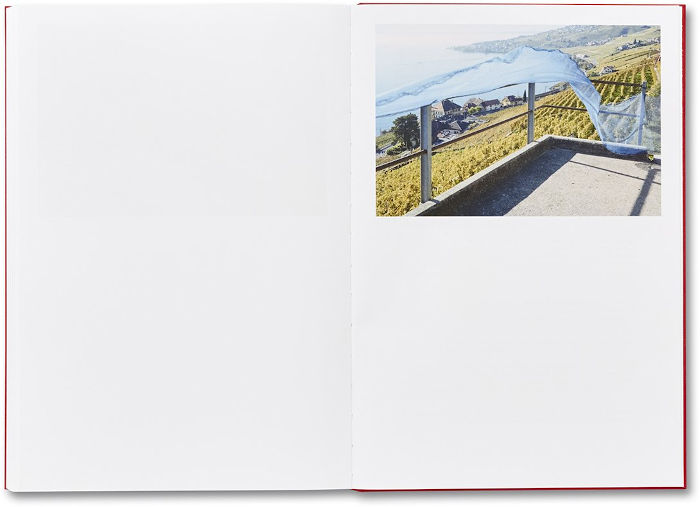

This image, taken in Rivaz, is familiar from the Blind Spot cover and is the last in Fernweh. It remains a favourite for reminding me of the quiet concentration of Fernweh’s ‘language without words’. The accompanying caption goes:

I rest at a concrete outcrop with a bunting of vintners’ blue nets, a blue the same colour as the lake. It is though something long awaited has come to fruition. A gust of wind suddenly sweeps in from across the lake. The curtain shifts and suddenly everything can be seen, the scales fall from our eyes. The landscape opens. No longer are we alone: they are with us now, have been all along, all our living and all our dead.

- Sindi-Leigh McBride is a researcher, writer and PhD candidate at the University of Basel. Follow her on Twitter.