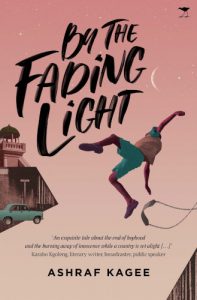

The JRB presents an excerpt from By the Fading Light, the new novel from European Union Literary Award-winner Ashraf Kagee.

By the Fading Light

Ashraf Kagee

Jacana Media, 2021

At two o’clock, as Ainey, Haroun and Cassius were washing down their Hertzoggies with Cocopina-flavoured Marshall mineral water, the news came on the wireless, preceded by the familiar official-sounding poop-poop-poop of Springbok Radio. Usually they paid little attention to news programmes, preferring to listen to music, especially those stations that played fast-paced rock-and-roll. But here was the newsreader, Eric Egan, keeping everyone up to date with the day’s events. It appeared that some people in Jo’burg had been arrested for being against the government. None of the boys quite grasped what the government was, or why anyone needed to be against it, and there was no one around to explain it to them.

In international news, there’d been a huge snowfall in New York that brought most of the city to a standstill. And Elvis Presley had given a press conference. That last titbit piqued their interest: all three were enchanted with the music of the King. On visits to Cassius’s house, they’d routinely spin the discs that took them back three or four years to when Elvis was at the height of his powers, the era of ‘Blue Suede Shoes’, ‘Hound Dog’ and ‘Don’t Be Cruel’. The newsreels at the Palace Bioscope had shown the King in army uniform, grinning and waving at fans, his hair cropped short as he prepared to commence his military service—a far cry from the coiffed, side-burned, pouting young rebel of ‘Jailhouse Rock’. And now came the announcement that he’d been released from the army. Perhaps the world would see some invigorating energy on the music scene again. Cliff Richard had toured the Union on his way to Australia and New Zealand earlier that year. But otherwise, no international rock-and-roll act of any importance had ever played in Cape Town, and if they ever did it would probably be to whites-only audiences anyway.

After the news ended, Ainey tuned the radio to their favourite music station, LM Radio, broadcast out of Lourenço Marques. Many South Africans were enamoured of its Top Twenty show, which gave generous airtime to young rockers—music that could not be heard on the local stations. On Ainey’s crackling wireless, LM Radio usually gave them hours of entertainment; but that afternoon’s offerings were uninspiring, just the insipid ballads of Pat Boone, Perry Como and Johnnie Ray.

‘Boring supremo!’ Ainey groaned when Jim Reeves asked plaintively, ‘Have I Told You Lately That I Love You?’ ‘Where’s the King, man?’

‘He’s probably warming up his voice,’ Haroun replied.

‘He should drink cod liver oil. They say it helps make your voice smooth,’ Cassius said. ‘My Uncle Damian says that anyway.’

Ainey and Haroun looked at him in disgust.

‘Ugghh … cod liver oil tastes like shit, man,’ Haroun said, wrinkling his nose.

‘Elvis doesn’t have to drink anything,’ Ainey said. ‘He’s voice is like golden syrup.’

‘It’s boring here,’ Ainey said. ‘Come we go to the Pit. We can go collect some nails for the waentjie.’ This was their go-cart, the components of which they were slowly in the process of collecting. They had thus far procured a wooden crate, courtesy of the Marshall Mineral Water Company, a couple of old planks that Mister had brought home from one of his building sites, and a rope they’d found in the store room of Kulsum’s shop. It would do for a steering device. Still required was a set of cast-iron wheels, and of course the nails to hammer the whole contraption together. The Pit, a junkyard close to the Woodstock railway station, was where such treasures were most likely to be found.

It was a remote, largely deserted area: a few railway houses built in the last century but now abandoned, old tires piled shoulder high, and sheets of rusted corrugated iron arranged haphazardly into makeshift sheds. At the far end was a disused two-storey building, which long ago had probably been used to repair locomotives. The Pit was a place steeped in gloom, where people seldom went, and where certainly no one went alone. Why the boys liked it was not clear to any of them. Despite its grim aura, it exerted an inexplicable pull, perhaps because it was an escape from humdrum home life. Or because it was a place no one would think of looking for them—not even other kids came to play there. Perhaps even because, and this was not something they’d ever admit, none of them felt quite accepted by the other neighbourhood boys.

The Pit was a refuge, a temporary reprieve from the social margins of Salt River. It was also considered an especially dangerous place on account of its desolation and distance from the houses. Perhaps it was this sense of the forbidden and the possibility of danger that attracted them to the place. But danger from what? No one could or would say, exactly. It was sometimes inhabited by the odd hobo or two, but they were usually too inebriated on cheap wine to present much of a threat.

‘My mother told me not to go to there,’ Haroun said. ‘It’s not safe. Not after what happened to Amin.’

Amin. He was everywhere and nowhere, even in his absence. Heck, because of his absence.

‘My mother told me not to go to there,’ Ainey teased him in a baby voice. ‘It’s not safe.’

‘What are you, man or mouse?’ Cassius wanted to know.

‘Your mother gonna change your nappies until you’re twenty-one?’ Ainey demanded.

Haroun stared at them. The mystery of what had happened to Amin was worrying, terrifying in fact. But his friends were right. He needed to make some decisions for himself. Maybe he could just lie to his mother if she asked where he’d been.

‘Ok, come we go,’ he said. ‘But I can’t get home too late.’

It was a half-hour walk to the junkyard, which was situated just before Woodstock Beach, across the railway line. The boys walked down Cecil Road, turned left at Tennyson Street, and then made their way along the main road. This was a busy hubbub of activity, with street sellers, horse-and-carts, hawkers, pickpockets, children begging for tickeys, and double-decker buses swerving towards the pavement to off-load passengers. A man jived past, holding a small transistor radio to his ear. He jerked his head back and forth to the beat, staring at them with wide eyes, as if to jeer at them for their misfortune at not sharing his auditory pleasure. A toddler was in the process of throwing a tantrum on the pavement, its hapless mother trying to whack its nappied rump with a rolled-up newspaper. The fish cart had made its way from the mosque to the main road and the driver was now engaged in a heated debate with a rather shrill customer about the freshness of the snoek he’d just sold to her. Considering the lateness of the afternoon, the customer might have a point. After all, the snoek had been caught at six o’clock that morning and been exposed to the hot sun ever since.

The boys passed Valli’s Barbershop, run by four virtually identical brothers. All the boys at Cecil Road Primary had suffered significant losses of hair to the Vallis a year ago, when an epidemic of lice broke out at the school. It was decided by Principal Mosavel that all sixty-eight scholars of the male persuasion would have their heads shaved clean. The Vallis had gleefully obliged, almost panting with excitement as they baldified their reluctant customers with their razors. In the age of ducktails and oiled pompadours sported by even the youngest male members of society, opportunities such as these were few and far between, and the Vallis made the most of it. Now the boys marched past the barbershop at a brisk clip, not looking right or left. Three Vallis watched them with gleaming eyes, their heads turning in unison as they passed. Presumably the fourth was inside, separating some unfortunate victim from his locks.

‘They’re like one-eyed cats peeping in a seafood store,’ Cassius muttered to the others.

They passed Oblowitz, the department store run by a Jewish family who had some time ago fled the pogroms of Eastern Europe and found sanctuary in South Africa. Window mannequins showing off the latest in ladies’ fashions stared vacantly as they went by. They passed the Palace Music Store, where a song was blaring from a jukebox. It was Dion of the Belmonts, declaring himself a ‘Teenager in Love’—which caused each boy to place two fingers in his mouth and feign a puke. Corny, smaltzy warbling was not for them. No doubt about that. No sirree bob. Ainey, Haroun and Cassius were rock-and-roll men. Where were Chuck Berry and Little Richard and Jerry Lee when you needed them? They walked on, past the Palace Bioscope where Black Orpheus was showing, the Brazilian film set in a Rio favela not unlike some parts of District Six. It had attracted some attention, as it wasn’t often that Brazilian films were shown, and with so many black actors to boot. All three boys found themselves drawn like magnets to the picture of Marpessa Dawn, whose fleshy thighs were displayed prominently on the poster outside the Palace.

Next to the Palace was a block of small shops, including a defunct ventriloquist’s studio that had been boarded up ever since they could remember. It was rumoured that the ventriloquist, a certain Mr Magoo, had been performing his act at a talent show one evening in a state of extreme inebriation. Magoo, so the story went, had become jealous of his dummy, who provoked larger quantities of laughter from audiences than Magoo himself did. He’d taken out a revolver and shot the imposter, supposedly in the heart, or wherever the heart might be in a dummy. The audience, consisting mainly of mothers and children, shrieked in terror and made for the door en masse. Miraculously no one was injured in the stampede, but Mr Magoo, protesting vehemently at the injustice of it all, succumbed to the police when they arrived and was never seen again.

The boys crossed the street. Now the properties were further apart, with large empty plots separating them. They passed a house where the curtains were tightly drawn, the doors and windows firmly shut. A weeping willow stood in the small front garden, giving the place a forlorn air, as if a tragedy had occurred there long ago, or perhaps not so long.

‘This house gives me the creeps,’ Ainey said. His voice was soft, in case the home’s occupants could hear him.

And Cassius: ‘Yep, me too.’

‘Doesn’t that old lady live here? Sis Ghava or something. She never comes out of her house.’

‘Ja, everyone says she’s strange.’

The house seemed to stare back at them grimly.

‘Never mind. We don’t know what goes on in there.

Come on, the sun will be setting soon.’

They crossed the railway line and as they approached the Pit. Table Mountain in the distance seemed to assume a frown, giving the scene an eerie feel in the dwindling sunlight. The secluded area was cordoned off by a barbed-wire fence. A sign saying ‘Strictly No Entry’ hung at an angle on the locked gate. They ignored it, getting down on their tummies to slide under the fence. All three knew they were not supposed to be there. Not under any circumstances, and certainly not now, after their friend had disappeared.

~~~

- Ashraf Kagee is a psychologist, academic and writer. He studied in South Africa and the United States and is currently Distinguished Professor of Psychology at Stellenbosch University. His first novel, Khalil’s Journey, won the European Union Literary Award in 2012 and the South African Literary Award in 2013. By the Fading Light is his second novel.

Publisher information

The sun begins to set and twilight falls over the Cape Town suburb of Salt River. The year is 1960, the year of the Sharpeville massacre. Three friends, Ainey, Haroun and Cassius, comrades in arms and merry pranksters, make a discovery that changes their lives. Mired in their troubled families, they valiantly struggle through their childhood. With the help of a mysterious yet powerful woman they confront an awful truth that forever changes their lives …

The prologue of By the Fading Light sets up the story by an unidentified narrator who, it is later discovered, is one of the three main characters, now grown up, reflecting on the past. A young boy, Amin Gabriels, disappears, an event that creates fear and anxiety in the community, especially for his friends, the main characters, who are three eleven-year-old boys, Ainey, Haroun and Cassius.

The boys’ adventures offer a poignant, compelling but also humorous glimpse into the world from their youthful perspectives. Ainey lives with his fussy grandmother and his authoritarian father who blames him for his mother’s death. Haroun lives with his depressed mother and bigamist father. Cassius lives with his sister and snobbish mother who wishes that she were white. Through these and other minor characters, a mysterious yet powerful older woman, a police officer, and a murderer, the reader encounters a spirited and robust community.

With its elements of historical fiction, literary realism and absurdist humour, By the Fading Light weaves together themes of troubled families, vibrant Muslim culture, South African politics, the resilience of children, loss of innocence and coming of age.

If only a young boy had not taken the long way home on a cold winter’s day. If only he had gone straight home, things might have been different. But he did not, and events in the tight-knit community of Salt River take a turn that inspire fear …