In a new anthology on death and dying, Sisonke Msimang writes about the multiple losses faced when her mother passed away. She not only had to deal with her own grief but also that of her six-year-old daughter, who had lost her grandmother, she writes in Our Ghosts Were Once People, edited by Bongani Kona.

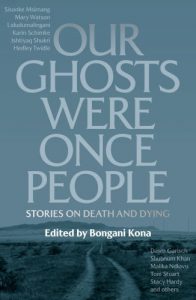

Our Ghosts Were Once People: Stories on Death and Dying

Edited by Bongani Kona

Jonathan Ball Publishers

Listen to Msimang reading the excerpt here:

12

For weeks I cannot sleep. My mother asks, ‘What kind of child can’t sleep?’ I am ashamed of my anxiety. Her judgement doesn’t help. I lie awake, nearly every night, worrying about the fact that one day I will die. Most of the time this is a low-level dread, but at night, before I sleep, I feel it in my chest—the weight of it too large for my growing frame. I imagine myself in a coffin but tell myself this is silly because when I am dead, I will not feel a thing. But the idea of feeling nothing is so appalling, so frightfully blank, that I rear up in my bed, sobbing.

Finally, one night I go in search of my father and he tells me it is normal and says he wishes he believed in God because that might help, but he doesn’t so I’m going to have to stare it in the face. He assures me it will be a long time before I need to worry about death. I don’t believe him, but I carry on regardless. Accepting that I will die—even if I hate it—is the first heartbreak I have encountered about which nothing can be done.

Death is an immovable, unbreakable truth.

I have been scared of dying since I turned 12 in 1986, the year of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster during the late stage of the Cold War. America and the Soviet Union were constantly on the verge of blowing up the planet, stockpiling nuclear bombs in the futile hope that whoever pressed the button first would die last.

It was also in 1986 that the space shuttle Challenger exploded in the sky, broadcast live on television.

Seven American astronauts were incinerated, and for a long time afterwards I could not look up without thinking of their burning bodies turned instantly into ash in the sky. My family was living in Canada at the time, and because of how close we were to America, it felt as though that terrible fire had burned in our own skies. I was certain there were astronaut ashes in the rain and in the Rideau Canal across which we skated when it was frozen in winter. I was sure little particles of them were in the snow that made everything muffled and cold for months on end until spring suddenly appeared.

The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done, there is nothing new under the sun. [Ecclesiastes 1:9]

The Challenger crash was my first memory of watching and re-watching death on television. I remember being astounded by the blueness of the sky and the brilliance of the day. There was no forewarning. Fifteen years later I had the same feeling watching a plane speed up and crash into twin towers on another perfectly sunny day. Death doesn’t always announce its arrival with dark skies and thunder.

In my twenties I occupied the carefree gap between adolescence and childbearing. I was so busy living, I forgot to worry about death. Both my surviving grandparents passed away during this decade, but I had grown up in another country without them. I barely knew them, so I did not grieve them as deeply as my father did. He loved them of course, but I suspect he cried also for the 30 years he had lost in exile and for the decades he had lived as though they were dead, though they were alive the whole time, awaiting his return.

I was 34 when my first child was born. The minute she was delivered I began to live with the fear that she might die or that I might die and leave her orphaned. She was tiny and yet such a heavy burden; so heavy I forgot she was also a joy. Through her existence I was suddenly invested in the project of immortality. I wanted her to live and yet quite suddenly there were signs that the condition of the world was deteriorating. It was 2008 and there were warnings that all our lives were in peril.

34

I look at the veins under her newborn skin and they remind me of waterways running off a large river. Her eyelids are a criss-cross of tiny streams. The planet replicates itself in our bodies and in a haze of maternal love and fear. I realise that now there is more for me to worry about than just the ozone layer and nuclear apocalypse. The seas are full of plastic and the temperatures are rising and I feel these tragedies in my womb. I clench and feel the blood flow. This love is a new kind of grief and in her first hours of life I begin to mourn a sadness that is yet to come.

When I was 41, my mother died. Grief—a word that seemed too small to encompass the world I had been plunged into. The feeling was bigger than my heart, bigger than my ribcage. It was larger still than Mummy’s bed, which I slept in every night for weeks, not wanting to lose her scent. Grief was a constant; it was grit in my eyes, the loss of taste, and limbs too heavy to lift. Grief was my daughter—all six years of her—too scared to ask me anything because she knew that her questions might break those pieces of me that resembled the mother she had known before her Gogo had died.

41

The two of them—my mother and my daughter—are in the garden. My mother plants spinach and my daughter attempts to feed the dogs grapes. They wander in loose comfort—the child as much in her element as the grandmother. At the chicken coop they stop to gather eggs. My child is fearless and doesn’t mind the squawking hens. They wander through fruit trees and chatter away like the best friends they are. She is the first grandchild; the one who has been adored for the longest time.

The last time they see each other, the night my mother dies, my daughter crawls into her lap and they cuddle on the big couch in front of the big TV downstairs in the big house that belongs to us all. This house has arms long enough to wrap around us all. Bedrooms and balconies and a kitchen big enough to sit in.

I notice that my mother’s hands are puffy and her face is tired. I tell her to drink her medicine. Her arms squeeze her grandbaby and she says of course she will. She doesn’t. The tragedy has already been scripted. We are living through the last lines of the book of her life and we do not yet know it. Hours later, cradled by her bathtub in the house she loves, surrounded by her children and their children, my mother dies.

My sadness at my mother’s death is compounded by my daughter’s confusion. What do you call this? Sadness squared perhaps. But the two of us are not alone in our sense of abandonment. We are all bereft—my sisters and our husbands and my father, who becomes a ghost of himself almost immediately. Heartache multiplied by infinity.

I never imagined what it might mean for my daughter to lose my mother. I thought only about her losing me. This is the problem with the calculus of risk; you never quite get the formula right.

Insurance policies ask what you will do in the event that both spouses die, but tragedy’s portfolio is complex. I never considered that I would lose my mother at the same time that my daughter would lose her grandmother; multiple losses embodied in one woman’s unexpected death.

The rituals that followed—the vigils and the singing and condolences—gave shape to our mourning. ‘But after the early bursts of tears, after the praises have been spoken, and the good days remembered, and the lament cried, and the grave closed, there is no company in grief,’ says American author Ursula Le Guin. ‘It is a burden borne alone.’

After the mourning, as grief set in and hardened, there followed a time of utter desolation. Her death sent me into the territory of panic I had first encountered at 12. I was no longer 12, but I was still terrified by the knowledge that she had been claimed by what James Baldwin describes as the ‘terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return’.

46

This has been a pandemic of a year but still somehow this miraculous thing has happened to my daughter’s body. She has stretched and blossomed and suddenly there is this and she is in tears and does not want to grow up and we are staring at one another in shock and grief and wonder. I assume she can bear life and it makes me sad and strangely complete to know that one day I will have outlived my usefulness to the planet, and she will remember me, and, in this way, I too will live.

I had no more answers in the wake of my mother’s death than I did when I lay shuddering in my bed in the months after the Challenger exploded. What I had—what I have always had—is an instinct to survive. And this instinct—so clear in the very fact of my daughter and the need for me to keep her safe—has been my saving grace.

As a child I wept at the sight of seven men and women burning on the television screen. As a young woman I cried at the sight of a plane crashing into sky and steel. In the months that followed, as war rained on innocents in the aftermath, I marched to mourn the deaths of strangers. In my forties I lost my mother and felt that I would die from the pain of it.

Through it all, I have been fearful and anxious and still I have stared death in the face. Life’s hardest moments do not require courage, they simply require accompaniment. And this I have had in abundance all the days of my life.

- Sisonke Msimang is the author of Always Another Country: A Memoir of Exile and Home and The Resurrection of Winnie Mandela.

~~~

Publisher information

‘I would get out of the car at every shopping centre and want to ask the stranger walking by with their trolley: “Why are you still shopping? Someone I love has died.”’

Death is a fact of life but the experience of grief is as unique to each of us as our fingerprints. This poignant and thought-provoking anthology gives us portraits of grief as seen through the eyes of writers and poets such as Sisonke Msimang, Dawn Garisch, Lidudumalingani, Mary Watson, Ishtiyaq Shukri, Hedley Twidle, Karin Schimke, Khadija Patel, Shubnum Khan and many others.

The contributions range from the deeply personal: a poet chronicles her relationship with her troubled, abusive father, a World War II survivor—to the political: an investigator from the Missing Persons Task Team draws us into the ongoing search for the remains of activists who were murdered by the apartheid state between 1960 and 1994—to the philosophical: a writer ponders the ethics of killing small animals.

Perhaps grief never truly ends but these stories transform the pain of death into something beautiful so that we can find ways to live with loss.

❤️🫂