This week, The JRB has been publishing the winning stories from this year’s Short Story Day Africa Prize.

The winners of the 2020/21 Short Story Day Africa Prize were announced on Monday. This year’s winner is Idza Luhumyo from Kenya, for her story ‘Five Years Next Sunday’. Zambian writer Mbozi Haimbe earned 1st Runner up for her story ‘Shelter’, and Alithanayn Abdulkareem of Nigeria was 2nd Runner with ‘Static’.

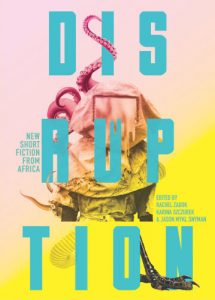

The winners will receive prize money of $800 (about R11,400), $200 and $100, respectively, and their stories, along with the rest of the longlist, will be published in Disruption: New Short Fiction from Africa, due out from Catalyst Press in September 2021.

Today, we’re sharing the full text of ‘Five Years Next Sunday’. Read ‘Static’ here, and ‘Shelter’ here.

~~~

Five Years Next Sunday

Idza Luhumyo

Winner of the 2019/20 Short Story Day Africa Prize

My locs are just shy of five years. They flow, like water. They are fluffy and black. They are dark. I forbid anyone to touch them. I use a black scarf to cover them. And how they coil, and how heavy they are, weighing me down with the expectations of my quarter. We are in the fourth year without rain. A sack of maize is gold. Water is divine. Here is a lesson we have learned: there is thirst and then there is thirst. And believe me when I tell you that we don’t remember it, a time when we did not know such thirst, such dryness inside our mouths.

It is an afternoon when Neema calls me to her side and hands me two hundred shillings for the ten-litre jerrican of DWL water. ‘Go to Jumaa’s shop,’ she says. ‘His prices are better.’ As security—’You never know,’ Neema says—she sends my brothers to the shop with me. They are to flank me, like bodyguards. We walk in silence, having never exchanged more than a few sentences in our lives. They don’t even use the cups I use, these brothers-mine, not even the house slippers I wear. When we get to Jumaa’s shop, I stand under the awning and wait my turn. My brothers fall back, mock-fighting each other, sniggering, doing whatever it is teenage boys do when they are caught between too much time and too little space. Then one of the coins I have in my hands falls. I bend to pick it up. My scarf falls to the ground. My hair is out. There is a gasp, not mine. When I stand straight, he has my scarf in his hands, and his mouth is open. A white man. Stocky, sunken eyes; something parched about him. And not the thirst we all have, having known no rain in the past three years. Something neglected, something dry and dead, as if from childhood. What in him needs watering?

‘Your hair,’ he says. ‘Beautiful.’

He reaches out to touch. He stops short when he sees the hard glare in my eyes. ‘I’m sorry,’ he stammers. Everybody knows it, he is Zubeda’s mzungu. What business does he have going around touching people’s hair? Out of nowhere, Zubeda herself emerges. Her eyes on me are daggers. She pulls him away. Mzungu wangu, the eyes say. Jumaa, the shopkeeper, laughs and laughs. ‘You’ve confused mzungu wa wenyewe jamani,’ he says to me. I don’t laugh. The white man has gone with my scarf. Open to the world, my hair is heavy.

The next day, he is at my father’s door, the white man. I smell him before I see him, my eyes peeping through the grille of my bedroom window. My brother, the younger twin, goes to call my father. And then: ‘Pili,’ my father calls out. I shuffle to the sitting room. The man is seated on the couch. Still, that parched look about him, as if something is empty inside him, as if he is looking for anything—anything—to fill him up. His eyes are still on my head.

‘I brought your scarf,’ he says.

I look at him.

Baba speaks for me. ‘Thank you,’ he says.

A large smile on Baba’s mouth. Not once has he ever smiled at me in that way, sat me on his lap, eased and teased me out of a cry. But now? A wonder. And then Neema. Hearing about it later, after the white man has left, his eyes still on my hair and my father’s eternal laugh still clinging to the air, she will walk into my room, smiling, saying: ‘I hear you have a new friend.’ I will say nothing. In my head, I will hum the shock, and then the joy. How is it possible that she who has avoided me all my life is in my room, on my bed, talking to me about this hair that she fears so much? For years, she has not allowed me to call her mother. ‘Call me by name,’ she says to me, when I forget and call her Ma, as my brothers do. She has never forgiven me for choosing to become a caller, for growing the rain in my hair. So Neema I say, whenever I want to catch her attention. But today, a different song. She is smiling. She is calling me her kichuna. She is touching my hair, gently pulling at the scarf, saying: ‘Maybe you should stop wearing those scarves on your head.’ The shock, yes, but the joy. Ma, I want to say over and over and over again. That smile she gives me; I don’t want to lose it. So I promise to do it, just so I can look at her as my brothers do and say Ma.

About a week later, I come from the market and he is there again. My father and brothers are in the sitting room with him. All of them—they giggle, they laugh. In the kitchen, Ma is busy. The smell of garlic and ginger and dawa ya pilau sizzling in oil. Lemons. It is not Christmas but haki-ya-nani, isn’t this Christmas pilau? Tena complete with the pilipili ya kukaanga? Passion juice freshly squeezed. On the kitchen floor, the bales of maize flour and wheat flour, the jerricans of Pwani Oil, the packet after packet of Mumias Sugar. She sees me and smiles, then frowns. She tugs at the scarf on my head.

‘I thought we understood each other,’ she says. ‘Go remove it.’

He doesn’t take his eyes off the hair the entire time. He says his name is Seth. I don’t believe him. He looks nothing like a Seth. He is not alone. Next to him is someone who shares the colour of his skin, her eyes the saddest things I ever saw. She sits next to him like a child admonished, a little girl asked not to squirm, to sit still and not make a nuisance of herself. Everyone seems to be having a grand time. Except me and her. She has a thin red line for a lower lip, a defiant forehead, and eyes that seem to be pleading for anything (or everything?). We sit through my parents’ laughter and my brothers’ sniggering and the silent eating of the pilau served in my mother’s Christmas utensils. The TV is on. My father talks about the three- year drought. Shakes his head. Blames the government. The white man grunts to my father’s monologue, eyes on me. Later, they leave the sitting room to us, Ma leading the woman away. Her name is Honey. Ma laughs, says: ‘Honey, what a name.’ When they leave, Seth and I sit in silence. He is a strange man. Something thirsty about him.

‘I have to say again,’ he starts. ‘You have such beautiful hair.’

‘Thank you,’ I say, my mind thinking about honey, how it sticks, how it never goes bad, how it … tastes.

He cannot stop touching the hair. Sniffing it. The sacks of food to my parents, they keep coming and coming. Then my parents have an idea. They pull Seth aside, speak to him for hours. Money changes hands. Soon, my parents open a shop at the front of the house. They put Jumaa out of business.

‘There is no need for rain,’ they say. ‘No need for you to cut that hair.’

They smile. Ma smiles longest, strokes my hair. ‘Our blessing,’ she whispers.

They become plump, my parents; they struggle to walk. Months pass. My hair gets closer to the five-year mark. The drought thickens. Seth leaves Zubeda, settles into being with me. When he talks about my hair, stroking it, there is a choke in his voice. Business for my parents is booming. The money is coming in fast. They put the other shopkeepers in the quarter out of business. They bless the drought. They call me to their side.

‘No need for rain,’ they say.

My brothers, they nod, agreeing. Now they speak to me, telling me about their lives, their exploits in school, their antics. When they stop attending classes at Mombasa Aviation, no one admonishes them. There is money in the family business. Seth’s name becomes hallowed. My hair is a small god.

There are cars parked outside the house. My parents dig a well, install a pump, sell the water in twenty-litre jerricans at absurd prices. Sometimes thirty times the price. Sometimes fifty. My brothers, they start drawing up the plans for shops two, three, and four. My parents put something away for my brothers’ dowries. Ma starts to read books. To buy lifestyle magazines. Sunday afternoons she spends at Mombasa Resort, stretching out on a beach chair, now staring at the ocean, now with cucumbers on her eyes. They start to spend time at the sports club, attending piano recitals and plays. My father gets a subscription for Newsweek, the Times, Reader’s Digest. They think about buying the Swahili house next door. They will knock it down, put up something to go with their new personalities. They talk about the new house. It is right there in their minds, clear, concrete. There is so much culture in it: a record player emits New Orleans blues; potted plants jostle for sunlight by windowsills; heavy mauve velvet curtains block the light outside; large paintings draw their guests’ attention from the white coral stone walls; Persian carpets drink in the sounds of dailyness; the cypress furniture matches the deep brown of the mvule wood in the ceiling; the windows go from ceiling to floor; and the kitchen, glory of glories, opens out to a vibrant colourful garden, complete with a small pond, where the ducks—not meant to be eaten, mind you—mind their business and sway their lives away.

I turn twenty-three. Only a couple of weeks to the five-year mark. Ma is anxious, asking me at least twice a day: ‘No need for rain, sio?’ Soon, we will be entering the fifth year without rain. On Citizen TV, the experts from Israel are talking about how their own country is a desert, but look what they have done. My father smiles at me. His smile is a wink. ‘No need for rain,’ he mouths. It has become his song. He laughs. I laugh with him, calm him, reassure him.

Seth rents an apartment by the beach. Sometimes, to switch things up a little, we go to hotel rooms. He has money. He has whims. And yet, he looks like he is stuck, waiting on something. Night after night, he hangs his torso across the balcony rail, holding an unlit cigarette in his hand. He stares at the water.

‘Your parents think I am just another mzungu,’ he says one night.

‘No, they like you,’ I say.

‘They don’t like me,’ he says. Then turns to me with a smile, hard. ‘They like my money.’

‘But I like you,’ I say.

‘No,’ he responds. ‘You like Honey.’ Then he walks away.

He has friends. They are loud. They stare. They ask whether it is okay to reach out, touch my hair. It is just hair. And yet, ‘I have never seen such hair,’ is what they say. ‘It’s so … natural,’ they say. ‘Real.’

They shudder. They are almost always men. But sometimes, there are women too. No, not women. A woman. Honey. Of course, it is not her real name. None of them, including Seth, use their real names.

She has anxious eyes, Honey, a sweet smile, and a wild pretty heart caught up in a lost cause. On the wrong continent. I feel like I could like her and still keep my wits about me. I catch her staring at me. When our eyes meet, we laugh. We’ve been looking at each other all night. She is from Belgium by way of Iran, she says, when we finally start talking. ‘Same as Seth,’ she says. I cannot locate Iran on a map. I don’t believe her. Still, I forgive the lie. There is something about her that calls out to me, some sadness, some grittiness, some stoicism in the thick of things. She looks like she has seen the other side of the world, seen it inside-out, or outside-in, and, for that reason, has come to expect very little from it.

And yet.

That unguarded softness, as if she would yield to the slightest tenderness, to the first person who walked up to her and asked her real name, asked how she was doing, yaani, really doing. I want to scoop her up and save her. She keeps staring at me. I am unable to look away.

Another night. Honey pulls me away from the party of laughing men and asks whether I smoke. I shake my head, say no. Still, I accompany her outside.

‘They are all obsessed with that hair,’ she says. Flicks the cigarette ash, takes a drag. ‘You must be tired of it.’

I smile, say nothing.

‘Have you ever thought of cutting it, selling it?’ she says.

I scowl. ‘Sell my hair? Why?’

She catches the scorn, bounces it back to me with a scowl of her own, followed by a shake of her head.

‘You African women wear our hair all the time,’ she says. ‘Do you ever see us surprised?’

I finally get it. She is in love with Seth. Beyond herself. And so out of jealousy, or that perverse need to maim that which one loves, I say: ‘I don’t even love him, you know?’

She looks at me long, hard. She frowns, takes a drag of her cigarette. It’s the first time I have seen pure calm rage. Then she says: ‘Of course you don’t. Do you think wazungu are stupid?’ She is tapping her head as she says this. ‘That we don’t know it’s all about the money?’

Her eyes are ablaze. But I know defeated anger when I see it. I play my cards as I want, hurt her as deep as I can. ‘Even if I were to leave him,’ I say, ‘he still will not come to you.’

‘We both know it’s that stupid hair,’ she says.

She grinds the cigarette butt with the soles of her feet. She is barefoot.

Love burns.

Another party. She stares at me all night, so I follow her outside when she steps out to the balcony. She smokes the first cigarette in silence. She offers one to me. I take it. She is different today, tender.

‘What happens when you cut it?’ she asks.

‘Honey, why are you so obsessed with my hair?’

‘Because he loves it.’

‘Will you love anything he loves?’

‘Stop changing the subject. Tell me what happens when you cut it.’

‘You will not believe me,’ I say.

‘Try me.’

Here is what will happen, I want to say to her. It will rain, like it never has before. There will be anger. And even though the fear of thirst—and death—is strong, the fear of those who have the rain in their hair is stronger. So the men will come to me as soon as someone alerts them. It will probably be the twins who do it. The men will hold torches of fire in their hands. They will strip me of the colour, the red and the black and the white in the kisutu my sangazimi left behind; then the red studs I wear on the lobes of my ears; and even the blue slippers I will have on. I will be barefoot in my banishment. They will wrap me in black cotton cloth, dyed the night before, the black barely clinging to the fabric. It will work. I will feel so black inside. Bleak. My parents and siblings, they will stay in the shadows and watch me jump over the fire. The fire will be the test, the exam. There are two worlds, the men will say, during the speech before the fire. The world to the right of the flames, and then the world to the left of the flames. Safety is in these worlds. My parents, my siblings, the men—they will stay at the edges and watch. I will take my time. Then I will jump and fall right into the fire. From the edges will come the sounds of righteous vindication: my father’s yelp, my siblings’ clapping, the men’s stamping of feet. My mother will be quiet. Someone will scoop me up like a baby, ready to banish me to the quarter of witches, where all women who have the rain are sent. Someone else will begin the chant. And when I say everyone will join in the chant of mtsai, mtsai, mtsai –everyone including my mother and my father and my brothers—believe me.

But I don’t say all that to Honey.

‘Rain,’ I say instead. ‘It will rain.’

‘Oh. So you are one of those women, the callers?’ Honey says.

The expression on her face, something has come home to roost.

‘Yes,’ I say, guarded.

‘I’ve heard of them,’ she says, moving closer to me. ‘Who did you get it from?’

‘My father’s sister,’ I say. ‘My sangazimi.’

She is standing close, maybe too close, to me. She smokes in silence for a while, staring intently into my eyes. They are so intense, her eyes. Urgent, with the franticness of quick calculations. Her hair is a pixie cut, the bangs falling over her eyes. She has a round face. Her dimples are something difficult to forget. When she smiles at me, I feel rewarded. She lights a second cigarette. She says: ‘How old is your hair?’

‘Five years next Sunday,’ I answer.

‘You mean this coming Sunday?’

‘Yes.’

‘So you are ready, ripe?’

‘Yes.’

‘Will you do it?’

‘My family says there is no need.’

‘But it has not rained for years.’

‘Yes.’

‘You owe it to your quarter.’

‘Maybe. I’d have done it. But my family likes me now.’

‘Have they never loved you?’

‘Not quite. It’s the hair. They feared it.’

We fall quiet. Honey smokes another cigarette. Then another one. I watch her pull in with her mouth, then sigh out the rings of smoke.

‘I don’t love him, you know,’ she says, after another stretch of silence. She is talking as if she has resolved something in her head. ‘It’s just, he is like an addiction. There are people like that. Addictions. You don’t ever forget them, unless someone else comes along to undo the spell.’

We go quiet for a long time. A long time.

Then I say fuck it, and I break the silence. ‘Has someone come along?’ I ask. ‘To undo the spell.’

She smiles, Honey. ‘Yes,’ she says. ‘And she has the most amazing hair.’

I smile.

‘Just hair?’

‘No, not just the hair,’ she says. Then she smiles again and says: ‘She is also a caller. Says she got it from her sangazimi.’

I smile back at her. We stare at each other. The smoke from the cigarette, it rises to the sky, which is where I think our hearts are. In love, sky-high.

Sunday.

If you can imagine the buzz of bees, incessant, then you know how the men sound. They are everywhere, the white men: on the couch, standing by the window, even on Seth’s treasured writing desk. There are two men on the carpet, their palms cupping whisky glasses. The men have a wet and icy look in their eyes, that shimmer that comes after a gulp of one or two servings of good whisky. Seth has the best stuff. Smooth, like a problem easing away. He has a smile on his face when I get in. I shut the door behind me, shuffle out of my slippers. He gets up, comes up to me. Then Honey emerges from the kitchen. I stare at her, but she won’t look at me. Her lipstick, red, is smeared at the edges. As if she has been fighting something, or someone, with her mouth.

‘Hey,’ she mutters in my direction. Then a frown, as she makes her way to the couch. I nod at her and sit on the couch with Seth. He pulls me up, sets me on his lap. He hands me a glass of whisky. We drink in silence. I can feel the eyes of the men on me, on my hair. The air is loaded with the heaviness of something unsaid.

Honey is stretched out on one of the sofas. She is staring at us. Then she gets up and comes to where I am. ‘Come,’ she tells me. ‘I want to show you something.’

We walk down the hallway and stop at an abstract painting suffused with various hues of blue. Before I can wrap my head around all the colour, Honey lifts the painting and pushes the wall. It is a secret door, opening into a large room with white walls. And black skin.

‘Seth likes the walls white,’ Honey says. ‘He thinks it’s the perfect backdrop for the display of black skin.’

There is something soft in how she talks about Seth, something like how mothers talk about the errant ways of their spoiled children.

And how much skin there is. Acres of it. The women on the wall are all black, African. And they all have dreadlocks. There I am, with an entire corner wall to myself, as I have never seen myself before. Most of the photos have been taken surreptitiously; this is the first time I am seeing them. The hair is the focus. I can almost feel the camera walk all over for me. There is no part of my body that is not there. But the hair, my coils, they dominate everything. I stare at the wall in silence. Stunned.

‘You see?’ Honey says, the tenderness from that night back in her voice. ‘He only loves the hair, not you.’

‘I know that,’ I say.

‘Then cut it. He will lose interest when you do. Then we can be together.’

‘But my family …’ I start.

‘No,’ Honey says. She moves closer to me. Her hands on my shoulders are fire. We are already so close to each other but I want to move closer, to bridge whatever distance is between us: two women from different parts of the world yearning for things that we are yet to name, to baptise. ‘I have money. Your parents will not care which mzungu gives them the money. I’ll keep them happy, okay?’

I stare at her.

‘Okay?’ she asks again. Her hand is now on my cheek. Her gaze is intense, scorching. I look away, but her hand on my cheek gently draws me back. ‘Trust me, okay?’ she says. ‘Cut it and everybody wins.’

I do it, right there in Seth’s house. I go to the kitchen, I rub the edges of two knives against each other, I put the edge of a knife to my coils. Honey sticks around until I am halfway through. She keeps looking outside, reporting on the gathering of the clouds, the darkening of the day, the flight of the birds. ‘Rain is coming,’ she whispers. ‘Keep going.’ She leaves the kitchen before I am done. She will wait for me in the living room with the others, she says. ‘So that it doesn’t look like it was my idea.’

There is only one word to describe the sound of rain after five years: magical. I am lighter. My soul, my head, even my voice. I can feel the wind on my scalp. But the anger, I can feel it too. Somebody will tip the men. They will come, torches of fire in their hands, looking for the one with rain in her hair. They did it to my sangazimi and her sangazimi before that. But I will have Honey. I will get to her before they get here. And then we will run away together.

I cut the last coil. Outside, thunder, then rain. I walk out of the kitchen. I walk into the living room. It is empty. No Seth. No Honey. No men. Outside, the rain keeps falling. I call out Honey’s name. My voice is a plea answered by an echoing silence. The rain outside is deafening. Then the lights go off. I switch on the torch on my phone. I go to the main door, open it. And that’s when I see them. I count five men. They are holding torches of fire, chanting mtsai, mtsai, mtsai. Then I see something—someone?—moving behind them, gliding away, like a snake. The pixie cut is unmistakable. In one of her hands, the coils of hair, coiling and coiling and coiling.

~~~

- Idza Luhumyo is a Kenyan writer with training in screenwriting and a background in law. Her artistic practice lies at the intersection of law, film, and literature. She is currently studying towards an MA in Comparative Literature at SOAS, University of London.

~~~

Publisher information

dis• rup • tion /dɪsˈrʌp.ʃən/ [noun] Disturbance or problems which interrupt an event, activity, or process.

This genre-spanning anthology explores the many ways that we grow, adapt, and survive in the face of our ever-changing global realities. In these evocative, often prescient, stories, new and emerging writers from across Africa investigate many of the pressing issues of our time: climate change, pandemics, social upheaval, surveillance, and more.

From a post-apocalyptic African village in Innocent Ilo’s ‘Before We Die Unwritten’, to space colonisation in Alithnayn Abdulkareem’s ‘Static’, to a mother’s attempt to save her infant from a dust storm in Mbozi Haimbe’s ‘Shelter’, Disruption illuminates change around and within, and our infallible capacity for hope amidst disaster. Facing our shared anxieties head on, these authors scrutinize assumptions and invent worlds that combine the fantastical with the probable, the colonial with the dystopian, and the intrepid with the powerless, in stories recognizing our collective future and our disparate present.

Disruption is the newest anthology from Short Story Day Africa, a non-profit organisation established to develop and share the diversity of Africa’s voices through publishing and writing workshops.

Edited by Jason Mykl Snyman, Karina M Szczurek, and Rachel Zadok.

7 thoughts on “[The JRB Daily] [Exclusive] Read ‘Five Years Next Sunday’ by Idza Luhumyo, winner of the 2019/20 Short Story Day Africa Prize”