The JRB presents an excerpt from African Cosmologies: Photography, Time, and the Other.

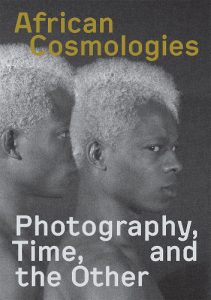

African Cosmologies: Photography, Time, and the Other

Fotofest

Schilt Publishing, 2021

Produced in conjunction with the FotoFest Biennial 2020 exhibition, African Cosmologies brings together thirty-three artists of African origin from around the world.

The artists’ works ‘challenge traditional notions of Blackness and transnational histories in relation to concepts of liberty, rights, and representation’.

FotoFest is the first and longest running photographic arts festival in the United States. It is the first time in the Biennial’s thirty-seven-year history that the central exhibition will focus on artists of African origin:

In their unique practices, the featured artists turn an eye to social, cultural, and political conditions that inform and influence concepts of representation as they pertain to image production and circulation in Africa and beyond. These artists question the ways in which subjectivity is constructed and deconstructed by the camera, and in the process, reveal legacies of resistance by those who defy traditional ideas of sexual, racial, gender-based, and other marginalised identities.

Wilfred Ukpong (France/Nigeria)

BC1-ND-FC: By and by, I Will Carry this Burden of Hope, till the Laments of my Newborn is Heard #2, 2017

From the series Blazing Century 1, Niger-Delta/Future-Cosmos, 2011–17

Mixed media

Courtesy of Wilfred Ukpong and Blazing Century Studios, NigeriaBC-1: NIGER-DELTA/FUTURE-COSMOS (2011–17) is the first instalment in a ten-part, multi-faceted art project titled Blazing Century (2011–). The project was conceived and developed by French-Nigerian and Oxford-based artist Wilfred Ukpong. Each series of Ukpong’s Blazing Century—titled BC1

to BC10—is site-specific and set within a geographical location, often one embroiled in socio-political and environmental issues, and filtered through a fictional and futuristic lens that redefines art’s role in building and shaping a future world.

In BC-1: NIGER-DELTA/FUTURE-COSMOS, Ukpong presents a series of staged photography, performative sculptures, and film and performance interventions that reference traditional Niger Delta rituals, ceremonial motifs, and symbols. These elements are patched together in contemporary art forms that underscore the complex relationship between the people of the Niger Delta and their environment.

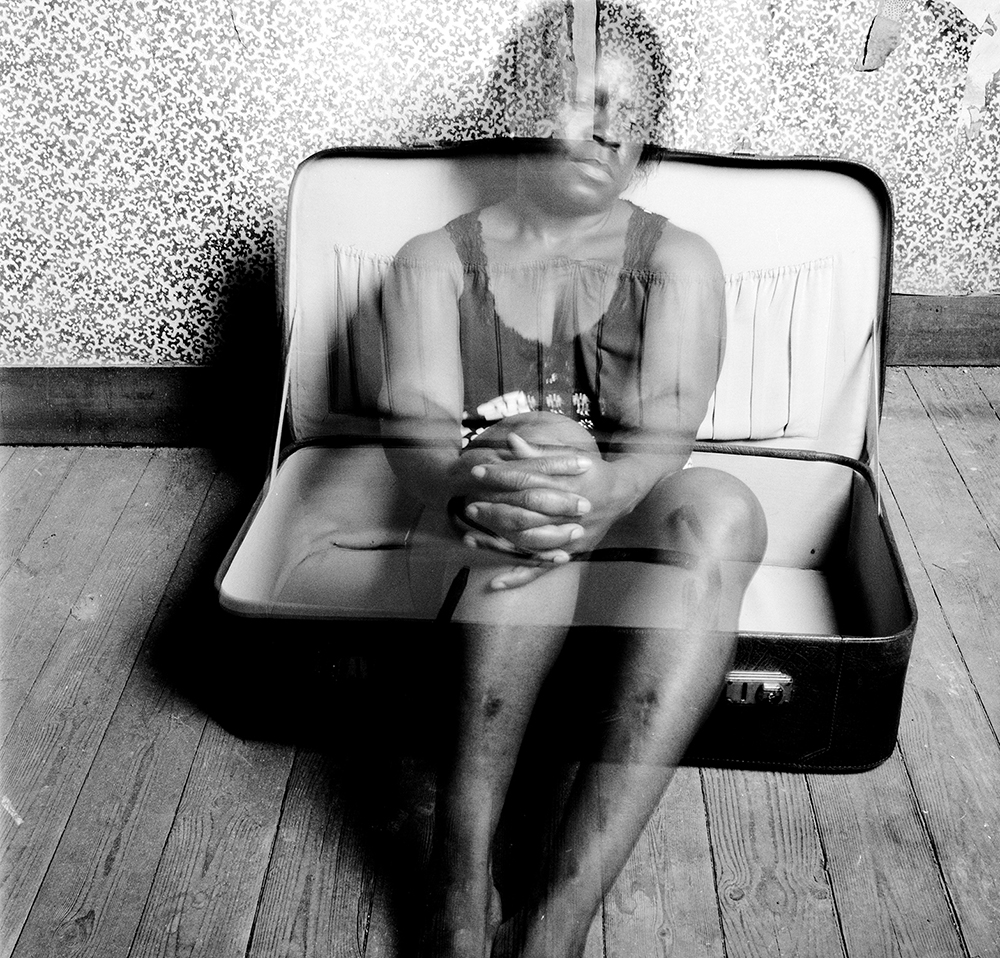

Hélène A Amouzou (Togo/Belgium)

Self-Portraits, 2008

Archival inkjet prints

Courtesy of Hélène A AmouzouTogo-born artist Hélène Amouzou captured this evocative and haunting series of self-portraits during the first year of a two-year period during which she sought asylum in Belgium. The ghostly quality of her figure represents her struggle to become a Belgian citizen, both legally and socially. Amouzou renders these photos of herself seated in the dimly lit attic above her transitional housing unit in stark black and white. The setting, with its cracked window frames, peeling wallpaper, and dying plants, seems as if it is crumbling, much like Amouzou’s resolve throughout the extended waiting period to receive her official residence visa. With her life in this state of flux, Amouzou’s portraits feel similarly unsettled. Her body floats in and out of her suitcases, never having felt comfortable enough to completely unpack, always ready to have to go back home.

Edson Chagas (Angola)

Oikonomos (EC-0678), 2011

Chromogenic print

Courtesy of Edson Chagas and Stevenson, Capetown and Johannesburg, South AfricaThe term Oikonomos originates from Ancient Greece, where it was used to describe the patriarchal leader of a household who was charged with overseeing a family’s economic, legal, marital, social, and political affairs. Borrowing this word for a series of self-portraits that feature the artist wearing various branded plastic shopping bags over his head, Edson Chagas proposes a relationship between national cultural identity and the homogenizing effects of Western capitalist influence and expansion. Rather than position a model in front of the camera wearing traditional Angolan masks as a commentary on the complexities of African historical lineages and cultural stereotypes, as the artist did in his series Tipo Passe (2014), in Oikonomos (2011–18), he avoids presenting cultural identifiers specific to any one group. The bag masks conceal the artist’s face, covering it with corporate logos, brand advertisements, political imagery, slogans from global tourist traps, and bland mass-produced designs. In these images, Chagas appears without any connection to a national identity; instead, he is presented as a global citizen, his personal and cultural identity withheld and eroded by the consumer culture. It’s clear that for the artist the figure of the oikonomos has been replaced by a global apparatus that refutes any notion of subjective agency by dictating all social, cultural, and economic affairs on behalf of the consumer class ‘family’.

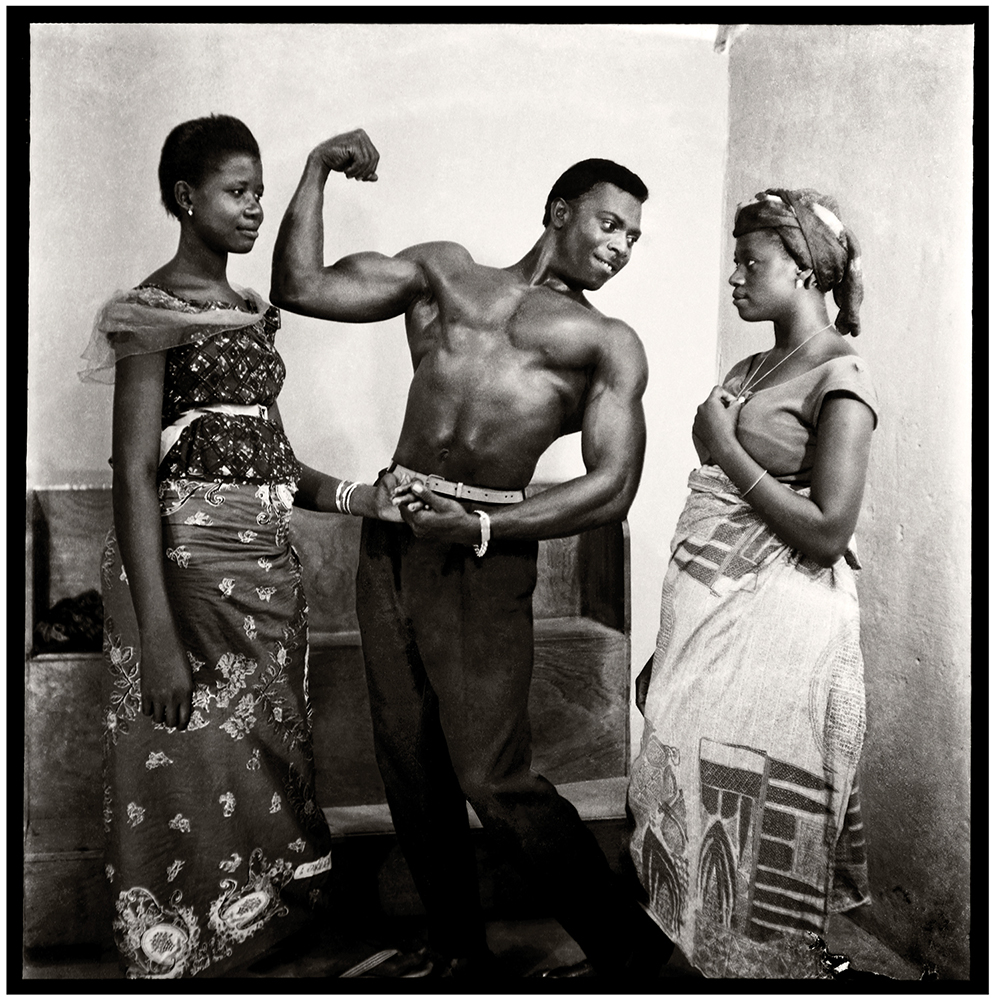

Jean Depara (Angola/Congo)

A bodybuilder with his girlfriends, Léopoldville-Kinshasa

From the series Athletes, 1955–65

Silver gelatin print

Courtesy of the Jean Depara Estate and Revue Noir, ParisIn 1960, after almost one hundred years of formal colonialism, the Belgian capital of Léopoldville became Kinshasa with the independence of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Despite this governmental restructuring, the city at first remained very much stratified into black and white social spheres. Angola-born Jean Depara photographed the cultural explosion that occurred in the city’s black sector in response to the loosening of these colonial ties. The free movement of people and a confluence of international media (especially American music and movies) influenced new types of personal, and, at times, even racially integrated expressions in Kinshasa; men and women of varying races danced unabashedly in nightclubs, men dressed as cowboys, and boys smoked hashish on the streets. One of Depara’s series features young bodybuilders who, proud of their chiseled bodies, paraded before female admirers at the pool of La Funa Sports Complex, a hotspot for relaxation and a meeting place for Kinshasans. Another of his series features young boys involved in a neighborhood gang called The Bills, a name adopted from popular American bandits of the West such as Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill Hickock, and Texas Bill. In the images, the boys are styled in the hip vigilante fashion of the time: Western-style cowboy boots and hats, plaid pearl-snap shirts, and denim jeans, with silver pistols hanging from their hips. It’s fitting that Kinshasans were influenced by images of the American West, as the era seemed to be imbued with a reckless air of abandon. This exciting time in the Democratic Republic of the Congo was of course short-lived, as the government eventually enacted a conservative culture that promoted oppressive laws, assimilation to a universal language, and sociocultural homogenisation. Depara’s documentary approach captures the spirit of his subjects, illuminating their individuality as decolonial subjects, able to explore themselves fully for the first time.

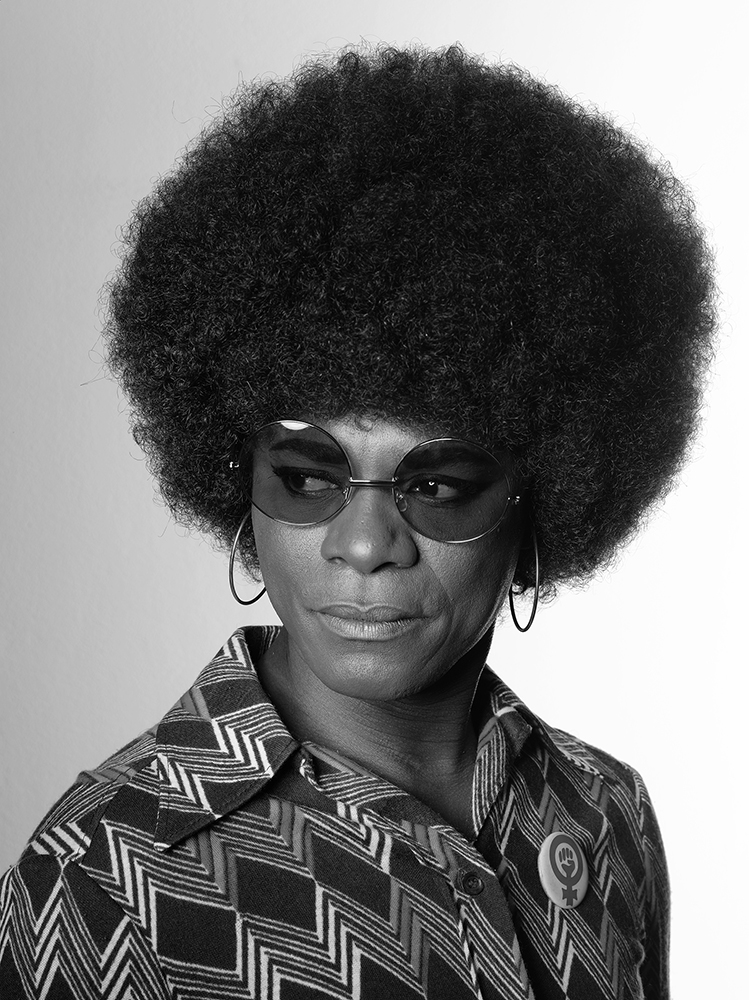

Samuel Fosso (Cameroon/France)

Autoportrait L_002993 (Angela Davis)

From the series African Spirits, 2008

Silver gelatin print

Courtesy of Samuel Fosso and Jean Marc Patras, ParisIn the series African Spirits (2008), established self-portraitist Samuel Fosso impersonates several historical figures associated with the Pan-Africanism liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s. This list includes Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah, and Congolese prime minister Patrice Lumumba, as well as figures from the African diaspora, such as Angela Davis, Malcolm X, and Muhammad Ali. In each photo, Fosso adopts their signature styles and recreates their most famous photographs, such as Martin Luther King, Jr’s 1963 Montgomery County Jail mugshot. In doing so, Fosso honours the legacies of these figures and the contributions they made towards the collective freedom of black people worldwide. The artist also asserts a critical diasporic vision of Africa, in which its descendants, no matter their physical location, are united by a common struggle. By imitating these leaders, Fosso resurrects them and recapitulates them into a timeline that extends their efforts into the present moment; Fosso’s portraits offer role models for those engaged in that collective struggle today.

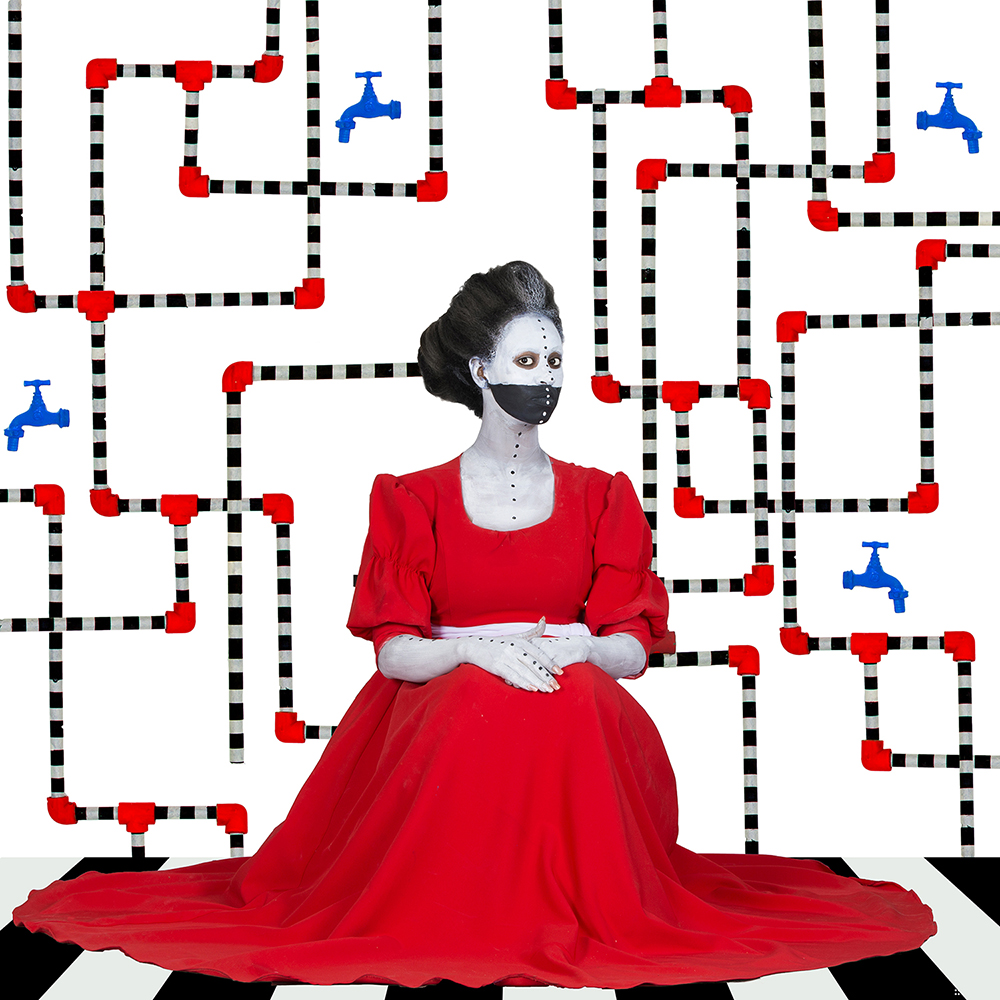

Aïda Muluneh (Ethiopia)

Access, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

From the series Water Life, 2018

Commissioned by Water Aid, 2018

Courtesy of Aïda Muluneh and Water AidIn her series Water Life, Aïda Muluneh examines patriarchal culture in rural Ethiopia through the question of water use and access. In Ethiopia, seeking and collecting water for the household is women’s work. This task demands that women traverse long stretches of inhospitable terrain hoisting large water jugs on their backs and atop their heads. Muluneh illustrates the inextricable relationship between the collection of water and Ethiopia’s patriarchy through a series of photographic vignettes, wherein women outfitted in brightly coloured garments and donning chalky face and body paint pose with the tools of their labour against surreal backgrounds that exaggerate the natural features of the East African desert landscape. The artist borrows from the aesthetics of Afrofuturism, combining traditional African cultural subjects (ideas, objects, and histories) with elements of minimalism and futurism to signify the radical potential of the women whose efforts provide the country with life-sustaining resources. Despite the prosperity that ready water access can bring, the water these women collect is never guaranteed to be clean. Among members of these remote communities, contaminated water is often a hidden conduit for disease transmission. Women’s health is affronted on two sides, by water-borne disease and by cultural oppression, which spreads unreservedly through communities and generations.

Zanele Muholi (South Africa)

Thulani II, Parktown, 2015

Courtesy of Zanele Muholi and Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New YorkOne of a series of striking self-portraits titled Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness (2015), this portrait of the nonbinary artist Zanele Muholi honours the approximately forty-four South African miners murdered by police during a workers’ strike at a Marikana mine in 2012. In the photograph, the artist faces the camera point-blank, bare-breasted, with an arresting stare. Muholi wears a miner’s leather helmet and goggles, transforming themself into a participant in one of the most painful moments in modern South African history. The photograph functions as a self-reflective psychological exercise for the artist, in which they confront the violence of this historical moment by projecting it onto their body, which has also been subjected to institutional and cultural violence. By casting themself in this moment, the artist is able to examine the collective oppression against a broad population of black people living in South Africa, whether it be physical and political assaults against their black female-coded body or police violence against the Marikana miners and their strike. As throughout the series, in this portrait, Muholi uses heavy contrast to exaggerate the darkness of their skin to the point where it may be mistaken for the soot that stained the miners as they worked. In the miners’ case and in Muholi’s, skin tone is a marker that cannot be removed, one that still predetermines the marginalisation of black people in post-apartheid South Africa. Muholi reclaims their darkness as something at which to marvel and as a tool to unite.

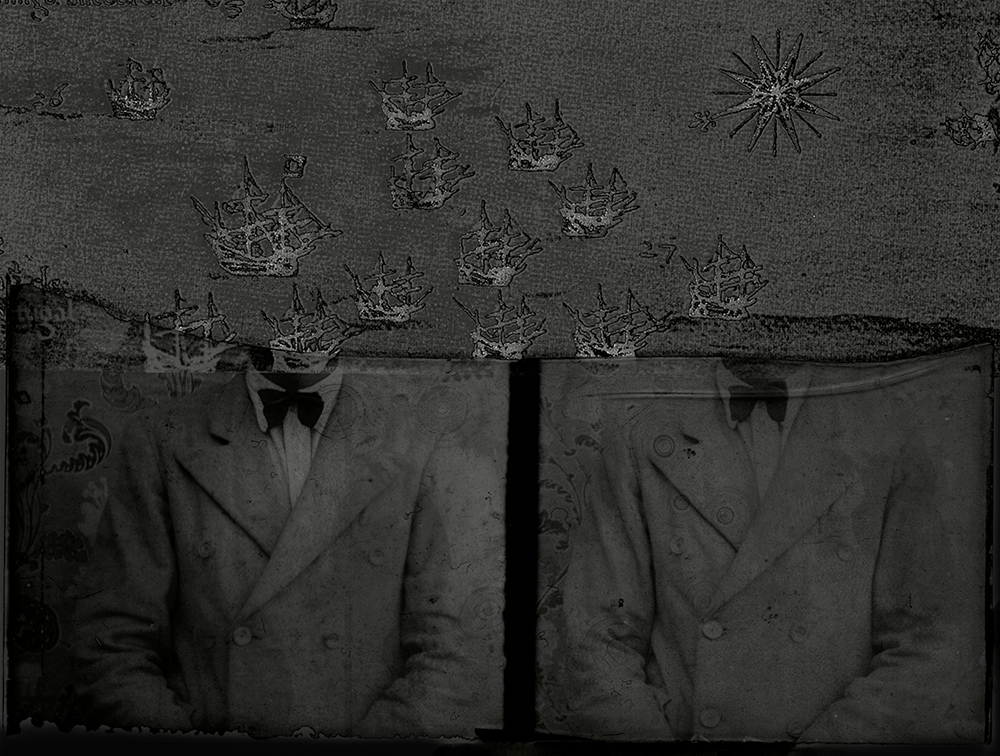

Eustaquio Neves (Brazil)

From the series Last Photograph, 2019.

Mixed media.

Courtesy of Eustaquio NevesBrazil’s national narrative treats its population as if it were a melting pot. However, much like the United States, Brazil has a legacy of African slavery, one that enforces strict racial boundaries to this day. Eustáquio Neves challenges the Brazilian racial hierarchy in two series, Arthuro (1993–1994) and Crispin (2008), which positively portray Black Brazilian subjects and traditions and call attention to their invisibility in representations of Brazil at large. The two characters Neves conceived for these series, Arthuro and Crispin, act as archetypes of men from isolated villages much like the one in which Neves grew up. These villages exist on the fringes of society, where whole communities of Black Brazilians have been pushed aside by a government that wishes to forget about them. In these communities, however, people are permitted to practice their traditions and, in doing so, resist assimilation into mainstream society, which would extinguish their traditional ways of life. Neves often depicts religious ceremonies and rituals, such as processions in which Arthuro and Crispin are the standard-bearers. He emphasises costumes, religious signifiers, and symbolic objects that typify these ceremonies. Utilising his knowledge of chemistry and chemical reactions in the developing process, Neves shrouds each photo with an aura of mystery so that these subjects cannot be fully reached by the viewer. Through this act of separation, Neves lets these subjects exist on their own plane, where they can play and perform without the discrimination they experience in Brazilian society.

Carrie Mae Weems (United States)

Magenta Colored Girl, 1989–2019

Archival pigment print

Courtesy of Carrie Mae Weems and Jack Shainman Gallery, NYAmerican artist Carrie Mae Weems assembles portraits of black adolescent boys and girls with intermittent empty colour panels in Colored People Grid. These photographs, tinted with multi-hued overlays of blue, orange, yellow, and pink, resist the strict dichotomy of the terms ‘black’ and ‘white’ used to describe race in the United States. Weems draws on the outdated expression ‘colored’ as a basis to investigate the hyper-fascination with colour that inaccurately represents Americans of African descent at the same time that it ostracises them in society at large. Expanding on that word, Weems imagines young black people in a range of expressive colours, working to break out of the mould of what ‘blackness’—as defined by the mainstream and the margins—means. The critical moment of adolescence, Weems finds, is to an extent predetermined for black Americans due to their entanglement in this colour hierarchy. Weems boldly reclaims and reinvigorates the concept of colour to complicate the racial status quo.