Mercy Dhliwayo chatted to The JRB Editor Jennifer Malec about family relationships, border jumping, and her debut collection of short stories, Bringing Us Back.

Mercy Dhliwayo

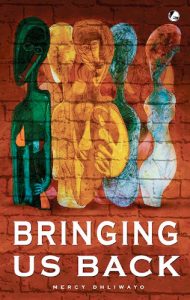

Bringing Us Back

Vhakololo Press

Jennifer Malec for The JRB: Vhakololo Press is a small independent publisher based in Limpopo, which aims to ‘cultivate a culture of reading and writing’. They are doing impressive work. Could you talk a little bit about the publication process and your experience of it?

Mercy Dhliwayo: So, sometime in 2018, when I was sitting with my MA in Creative Writing manuscript, still researching publishers who were accepting manuscripts, I came across Vhakololo Press’s call for submissions. I submitted my manuscript and sometime later in the year I received an email from the press advising me that my manuscript had been selected for publication. I was very happy and thought, wow, I’m one step away from being a published writer: ‘an author’ as our published friends like to say. Little did I know that the real work was yet to begin. The editing, the cutting out of what was considered excess fat, rewriting and, gosh, even chucking out an entire story or two. It was, however, rewarding having my work go through such a process before it was taken out to the public. What I enjoyed the most was being granted creative control over the final output and being able to defend certain aspects of my work that I felt needed to remain as they were—and being listened to. Overally, the experience was gratifying.

The JRB: You are also a hip-hop and spoken word artist, under the stage name Sista X. How did you find the process of writing prose—was it more difficult? Easier? How was it different?

Mercy Dhliwayo: I found the process of writing prose more demanding. Maybe it’s because I have been rapping and doing poetry longer than I have been writing prose. And with prose, there are writers whose works already set the bar high. Writers like Yvonne Vera, who arrests you in a piece of prose that leaves you engrossed by its language and aesthetics. Given the standards that such writers have set, there is always the challenge of trying to achieve a certain level of mastery and to mould an aesthetically satisfying piece of writing into existence, while maintaining, or rather, establishing one’s own identity in writing.

The JRB: I’ve read that your writing is influenced by Dambudzo Marechera and Ayi Kwei Armah, and I can certainly see that in this book. What is it about these writers that you wanted to emulate?

Mercy Dhliwayo: [laughs] Wow, where did you read that?

The JRB: I have my sources.

Mercy Dhliwayo: Yeah, man, like many, the first book I read from Ayi Kwei Armah was The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born. I was in high school then. Many years later the photographic imagery of that book still stays with me and I have always tried to emulate Armah’s poetic language, attention to detail and depiction of decay in my poetry. This has also filtered into my prose. The Healers also influenced some of my writing. Armah’s use of violence and the metaphor of disease, they way he depicts the different forms of violence and disease eating through modern day society, this is something that strongly resonates with my writing. With Marechera, he was daring in his writing and very unconventional. No subject matter or way of writing was a taboo to him. Zimbabwe has been a conservative country for the longest time, and it still retains some of that conservativeness. In the current political climate, the situation is worsened by political censorship, which, although it existed in Marechera’s time, one would not expect to continue existing under what is supposed to be a democratic dispensation. I have found Marechera’s boldness necessary in challenging the status quo. For example, in my story ‘Escaping the Flames’, it enabled me to acknowledge and explore the sexuality of marginalised women and to amplify the sinister voices that are often concealed inside the heads of ‘wounded’ and oppressed ‘good wives’. Inspired by Marechera, I intentionally strive to push literary boundaries through experimentation with form and language and I am also very intentional about the subjects I tackle.

The JRB: Your stories often centre around the disruption that is commonplace in many people’s lives. But you also write about the banality that accompanies a life of migration or destitution. In ‘Exodus’, a character crossing the border from Zimbabwe to South Africa says, ‘Again you walk – and walk. You think that if you were ever to tell of this exodus, the story would be pregnant with monotonous walking.’ Was this contrast something you wanted to explore?

Mercy Dhliwayo: To some extent, I think so. Thanks to the developments with the South African Zimbabwean Special Dispensation permit, I can openly say this without fear of incriminating myself: ‘Exodus’ is a ‘spiced up’ and fictionalised account of a real-life ‘border jumping’ experience I once had—my first and last, I must add. [laughs] Writing of this experience was difficult and was as dragging, as tiring and as monotonous as the walking itself was.

Long after I had finally finished this piece, I went for a recording session at some studio in Polokwane. There, I found a young Zimdancehall artist in the process of recording, and his session was overlapping into mine. The guy was visibly stoned, still had his green bottle in hand and could not maintain his balance. Rather than (typically) being annoyed at this stoned character, booze and all, using my recording slot, everything about this picture saddened me. More so after I heard what he was recording. He looked like one of those peaceful drunks, who just want to drink their sorrows away, cause no trouble and just stagger on home to sleep. Despite his state, he was able to perform his song. The Shona lyrics spoke about how he is working and keeps working and keeps working but his situation was not improving. Till today, I am still haunted by the lyrics and the beautiful way that he chanted them. So many foreigners keep working and working but do not see any change in their lives.

The repetitiveness of ‘I keep working and keep working …’ reminded me of ‘Exodus’ and the experience I was writing about. I remembered the walking, and the endless walking. While I may be better positioned than many of my fellow countrymen and women and other foreigners living in South Africa, I have always been conscious of the direness of the living conditions of some of us. Now, listening to this guy’s lament made me question the greenness of the pastures we seek across borders. It made me wonder if all that metaphorical walking was worth it for some of those I was walking with. To leave home and come and work … and work and work and then die without leaving behind even enough funds to bury you or to ferry you back home to be buried amongst your own. Of course circumstances differ from case to case, some come from wartorn countries, some flee worse hunger back home. But yeah, when I got home from the studio, I remember working that ‘monotonous walking’ section into ‘Exodus’ and also reworking some of the stories in the manuscript to try and explore the questions that I remained with after that studio encounter. To try and explore that state of stagnation.

The JRB: Language seems to be another interest of yours. In ‘Exodus’ there is tension between Shona and isiNdebele speakers, and in ‘Lioness’ a grandmother comments on the return of women from their work in South Africa:

…in drunken December, with their nice clothes and their gold teeth and Carvelas. And their Njiva accents and tongues that call plates izitsha (instead of imiganu) and rain imvula (instead of izulu) and expect our gods to still hear them when they pray—when our gods cannot even understand the foreign language that has taken over their tongues.

What is it about language in Southern Africa that interests you?

Mercy Dhliwayo: I love how Southern African languages are interconnected. You may be Shona or Tsonga, Ndebele or Zulu, but there are always common words that exist in these different languages, which reminds you that we are one after all. But despite that, we are still distinct people with our own cultures. And one concern that I have had for a long time now relates to the potential death of our languages as Zimbabweans, isiNdebele in particular. Already we have lost a lot to the dominance of English, such that some of our children speak English at home and cannot even converse in their own languages. And now with migration, often illegal migration, in a bid to conceal their foreignness, a number of Zimbabweans present themselves as Zulus. In the process, Ndebele words and accents have been replaced with everything Zulu to the extent that when our people return home, they maintain the Zuluness in their speech as if they have forgotten the proper Zimbabwean Ndebele. And this for me is another threat to the continued existence of the Ndebele language that I have tried to hint at in one or two stories.

The JRB: The first story in the collection, ‘Smashing Tomatoes’, is perhaps the most harrowing, as a fruit and vegetable vendor’s baby is killed by a senseless act of violence. Why did you decide to begin the collection with this particular story?

Mercy Dhliwayo: The whole collection is based on migration and displacement, physical and otherwise. It puts a spotlight on vices that push us from what is familiar into the perceived comfort of what is foreign. Starting the collection with ‘Smashing Tomatoes’ appeared to be fitting because the story begins at a point of destruction. Destruction of trust, hope, and sense of security. It chronicles the violence meted against a people by their own government or people. The violence that pushes its people away. But the violence is not always physical. It is manifested in various forms, such as hunger, depriving people of their means of survival, and harsh legislation and policies, just to name a few. As we proceed into the book and get into other stories we zoom into the lives of those who have already been pushed out and those who have been left behind. The collection then concludes with stories of those who have been away for too long and those we need to bring back home. So, over all, the intention was to be as systematic as possible about the chronological sequencing of the stories.

The JRB: Zama, a young LGBT person in the story ‘Nkululeko’, has some difficult decisions to make, and may surprise the reader with what she decides. This story, and many others in the book, illustrates the unfounded assumptions we may make about the lives of marginalised people. Was this complexity something you wanted to unpack in your writing?

Mercy Dhliwayo: Not consciously or intentionally, particularly with ‘Nkululeko’. Maybe with other stories like ‘Exodus’. With Nkululeko I wanted to pose a few questions. Questions like: what makes your sexual orientation better than the next person’s? What makes you more deserving of ‘home’ than the next person? I also wanted to use Zama to make a bold statement about who she was and assert her right to stay in a place she called home. In other stories, we see characters forced by circumstances to live outside the boundaries of home, but Zama has to fight against being pushed out, because we all deserve a place to call home, heterosexual or otherwise.

The JRB: In many of the stories, characters have strained or troubled relationships with their mothers. In ‘Plan B’ a teenage girl, who feels abandoned as her mother works far away, muses: ‘some feminine secrets are better kept as secrets even from other females—even if one of those females is one’s mother. After all, what right did her mother have to her secrets?’ Can you talk a little bit about why you wanted to explore these relationships?

Mercy Dhliwayo: The idea was really to focus on parent-child relations and not necessarily mother-daughter relations. But being a woman who had a mother being more present than the father, the mother-daughter route was easier to explore. Why this? They say charity begins at home. But so does depression, at least in my view. I feel like if things were well at home, if we had healthy parent-child relationships, there would be fewer depressed people out there. Lower suicide rates, because children, young adults, and even grown folks would be better equipped to deal with problems they encounter in life. But most of our relationships at home are fractured. Consequently, children come home with problems from school, problems with their peers or their boyfriends and girlfriends, but because the relationships at home are bad, there is no meaningful communication portal. Hence they block things inside, until unresolved issues accumulate and spiral into depression. Even if you have friends or other people to talk to outside of home, some of the problems actually stem from the same homes we go back to every day or night. It is for this reason that I found it essential to put a spotlight on family relations, in particular parent-child relations. We need to work on these relationships. I strongly believe that healthy parent-child relationships are pivotal in fighting depression and suicide.

The JRB: Humour is used sparingly in this book, but there is one story that made me laugh. In it, a young white American turns up for an important Sunday lunch at his Black girlfriend’s family house, to her horror, in faded tracksuit pants, scruffy elephant-hide sandals and an old khaki shirt decorated with marijuana plants and a portrait of Marcus Garvey. Where did the idea for this character come from?

Mercy Dhliwayo: [laughs] Antonio in ‘The American’ is a construct of society’s stereotype of artists and also a product of keen observation. He was particularly inspired by how some friends, family or colleagues (who are not really artists) tend to view and or speak of the free-spirited individuals we sometimes encounter in the artistic spaces we frequent and often invite these friends and family to. Their perspectives, although sometimes condescending, gave me a desire to write a character like Antonio into life. He is not one character, but a fusion of different real-life characters I have encountered here and there.

The JRB: Some of the stories in the book are quite experimental, form wise. One is written as a series of text messages, for example, while ‘Escaping the Flames’ is written in the imperative mood (full disclosure, I had to google that!) with the narrator speaking to herself but almost commanding the reader:

‘Allow him to come in.

‘Do not debate with yourself whether to let him speak first or whether you should speak first. Do the wifely thing. Greet him.’

Was this story more challenging to write? More fun? Could you speak a little about why you decided to use this approach?

Mercy Dhliwayo: Strangely, this particular piece was actually fun to write. With the whole collection, I intentionally wanted to be experimental. I wanted the stories to be told differently. Having already used traditional narratives, such as the first, second and third person narratives, I needed something totally different. And for ‘Escaping the Flames’, I wanted to empower that voice that the conscience tends to numb in persuading us to do what we know is morally right even when we are wronged. So when I finally decided on an approach to use, everything else just fell into place. The only challenge was trying to be consistent with the commanding voice I chose to use.

The JRB: In the book’s acknowledgements you thank your mother for being ‘the first to support my artistic and writing endeavours, even when their direction was not clear’. Do you think you have found your direction? What are you working on next?

Mercy Dhliwayo: It has never really been an issue of me not knowing the direction I wanted my art to take. A picture has always been there, although it kept evolving and developing as I grew as an individual. The issue rather revolves around the fact that, while you, as an artist, may have a clear picture of what you want to do with your art, well-meaning loved ones may not always really understand your vision. Hence, while being supportive, out of concern they still pose questions and offer unsolicited advice regarding your art and future. For them, it is a question of ‘where can your art take you’ as opposed to ‘where do you want to take your art’. The latter being the question that has always driven me as an artist. The vision for me has not changed much; I still want to write and make music and continue engaging with communities, on a grassroots level, through music, literature and the work that I do with the Slam Emporium PLK (a movement I co-founded that hosts poetry and hip-hop sessions in Polokwane). Regarding current works, I’m back in the studio working on an EP (another hip-hop project) while I’m also revisiting an earlier unpublished manuscript, reworking it in view of everything I’ve learnt in the past year with the hope of getting it ready for publication.

The JRB: Finally, because writers are usually wide-ranging readers, we like to ask for recommendations. What book or books have you been reading recently that we should too?

Mercy Dhliwayo: My book club (shout-out to Timbuktu Book Club!) is currently reading James Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain. That’s what I’m also reading and would recommend. It reminds me of Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, one of my old-time favourites. Back on the continent, I strongly recommend Busisiwe Mahlangu’s poetry collection Surviving Loss. I simply love it. Then there’s Fiston Mwanza Mujila and Namwali Serpell, two of my favorite contemporary writers; from them I recommend their books Tram 83 and The Old Drift, respectively. Mujila’s writing somehow reminds me of Marechera. For Marechera, I recommend Black Sunlight.

I also cannot wait to get myself a copy of Flora Veit-Wild’s They Called You Dambudzo: A Memoir. And last (but not least), of our very own contemporary Zimbabwean writers, among many other awesome writers, there is Philani Nyoni, who has been often compared to Marechera. My favourite of his poetry collections is Once A Lover Always A Fool. I actually love his prose more, and you can sample it in Afritondo’s collection Yellow Means Stay, which features his short story ‘Slick Dog: Diary of a Ninja’.

The JRB: Thank you for a wonderful conversation.