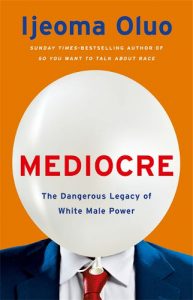

The JRB presents an excerpt from Mediocre: The Dangerous Legacy of White Male Power by Ijeoma Oluo, the bestselling author of So You Want to Talk About Race.

Mediocre: The Dangerous Legacy of White Male Power

Ijeoma Oluo

Hachette, 2021

‘Lord, give me the confidence of a mediocre white man.’

When writer Sarah Hagi said those words in 2015, they launched a thousand memes, T-shirts, and coffee mugs. The phrase has now become a regular part of the lexicon of many women and people of colour—especially those active on social media. The sentence struck a chord with so many of us because while we seemed to have to be better than everyone else to just get by, white men seemed to be encouraged in—and rewarded for—their mediocrity.

White male mediocrity seems to impact every aspect of our lives, and yet it only seems to be people who aren’t white men who recognise the imbalance.

I am not arguing that every white man is mediocre. I do not believe that any race or gender is predisposed to mediocrity. What I’m saying is that white male mediocrity is a baseline, the dominant narrative, and that everything in our society is centred around preserving white male power regardless of white male skill or talent. I also know that many white men accomplish great things. But I will argue that we condition white men to believe not only that the best they can hope to accomplish in life is a feeling of superiority over women and people of colour, but also that their superiority should be automatically granted them simply because they are white men. The rewarding of white male mediocrity not only limits the drive and imagination of white men; it also requires forced limitations on the success of women and people of colour in order to deliver on the promised white male supremacy. White male mediocrity harms us all.

When I talk about mediocrity, I am not talking about something bland and harmless. I’m talking about a cultural complacency with systems that are horrifically oppressive. I’m talking about a dedication to ignorance and hatred that leaves people dead, for no other reason than the fact that white men have been conditioned to believe that ignorance and hatred are their birthrights and that the effort of enlightenment and connection is an injustice they shouldn’t have to face.

When I talk about mediocrity, I talk about how we somehow agreed that wealthy white men are the best group to bring the rest of us prosperity, when their wealth was stolen from our labour.

When I talk about mediocrity, I am talking about how aggression equals leadership and arrogance equals strength—even if those white male traits harm the men themselves and the kingdom they hope to rule.

When I talk about mediocrity, I talk about success that is measured only by how much better white men are faring than people who aren’t white men.

When I talk about mediocrity, I am talking about the ways in which we can’t imagine an America where women aren’t sexually harassed at work, where our young people of colour aren’t funnelled into underresourced schools—all because it would challenge the idea of the white male as the centre of our country. This is not a benign mediocrity; it is brutal. It is a mediocrity that maintains a violent, sexist, racist status quo that robs our most promising of true greatness.

By defining greatness as a white man’s birthright, we immediately divorce it from real, quantifiable greatness—greatness that benefits, greatness that creates. White men have assumed inborn greatness, and they are taught to believe that they alone have seemingly infinite potential for greatness. Our culture has shaped the expectation of greatness exclusively around white men by erasing the achievements of women and people of colour from our histories, by excluding women and people of colour as heroes in our films and books, by ensuring that the qualified applicant pool is restricted to white male social networks.

But the expectation of accomplishment is not an accomplishment in and of itself. By making whiteness and maleness their own reward, we disincentivise white men from working to earn their privileged status. If you are constantly assumed to be great just for being white and male, why would you struggle to make a real contribution? Why take a risk or make a determined effort that might fail when you can be rewarded for keeping your head down? Societal incentives are toward mediocrity.

Most women and people of colour have to claw their way to any chance at success or power, have to work twice as hard as white men and prove themselves to be exceptional talents before we begin to entertain discussions of truly equal representation in our workplaces or government. Somehow, we don’t think white men should be required to shoulder any of the same burden for growth and struggle the rest of us are expected to work through in order to accomplish anything worthwhile.

How often have you heard the argument that we have to slowly implement gender and racial equality in order to not ‘shock’ society? Who is the ‘society’ that people are talking about? I can guarantee that women would be able to handle equal pay or a harassment-free work environment right now, with no ramp-up. I’m certain that people of colour would be able to deal with equal political representation and economic opportunity if they were made available today. So for whose benefit do we need to go so slowly? How can white men be our born leaders and at the same time so fragile that they cannot handle social progress?

What we have been told is great, thanks to the mediocre-white-man-industrial complex, just isn’t always that great. The image of the ideal white man—the bold and confident ones we end up idolising, giving promotions to, electing to office—that image is often the epitome of mediocrity. And when entrusted with these positions of power, such men often perform as well as someone with mediocre skills would be expected to: we see the results in our floundering businesses and in our deadlocked government. Rather than risk seeming weak by admitting mistakes, white men double down on them. Rather than consider women or people of colour as equally valid candidates for power, white men repeat that a change in leadership is somehow ‘too risky’ to entrust to groups that they have deliberately rendered ‘inexperienced.’

This discrepancy between our limited definition of greatness and what we’re left with comes in part from our insistence that our system is a meritocracy, when it clearly is not. There are all sorts of systems and institutional barriers that have worked for centuries to ensure that large segments of our society—regardless of talent, skill, or character—will never be allowed to rise out of poverty or powerlessness.

This country’s wealth was built on exploitation and violence, and those who worked hardest to build it were not empowered or enriched by its successes—they were enslaved people, migrant labourers, and domestic workers. Much of this country’s early infrastructure, for example, was built with slave labour, and then with grotesquely underpaid immigrant labour and prison labour. Many of our business and political leaders were freed to dedicate their time and energy to their professional success by the unpaid labour of wives and mothers and the underpaid labour of nannies and housekeepers.

Those who profited off that labour did little more than be born with a whip in their hand. But nevertheless we crafted a story of greatness around them. We say that they earned greatness, and that if we emulate them, these cruel and powerful white men, we will one day rise to where they stand.

When I say ‘we,’ I don’t mean me. I am a Black woman. True, I have been told time and time again that my best chance of success is to emulate the preferred traits of white maleness as much as possible. Still, mine is not the image of the great leaders in our history books, nor that of the heroes in our stories. For someone like me to expect any greatness without having exceptional talent and luck was, at best, foolish and, at worst, dangerous. This is not my birthright.

~~~

- Ijeoma Oluo is the author of the #1 New York Times bestseller So You Want to Talk About Race. Her work on race has been featured in the New York Times and the Washington Post. She has twice been named to the Root 100, and she received the 2018 Feminist Humanist Award from the American Humanist Association. She lives in Seattle, Washington, United States.