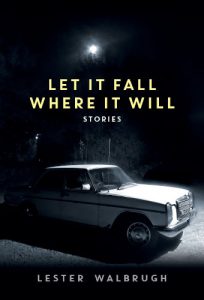

The JRB presents an excerpt from Let It Fall Where It Will, Lester Walbrugh‘s debut short story collection.

Lester Walbrugh

Let It Fall Where It Will

Karavan Press, 2020

Read the excerpt:

The House on the Corner

Like his mother, Emile Oliphant has always collected men. His mother called them her lovers. Emile calls them his life.

— Meet now?

— Do you have a place?

— No. Any ideas? I’m open.

— Bloubergstrand. The parking lot there?

— Give me twenty minutes. I’m in a blue Opel.

— White Golf.

— OK.

They met at the crepuscular beachfront. The stranger’s hand fell on his shoulder, and the frisson drew a gasp from Emile.

The couple sits against a granite boulder, their toes burrowing into sand.

‘You think it’s the Xhosa boys?’ Emile asks.

‘What is?’ Faizal scoops up a handful of sand and lets it trickle through his fingers.

‘The fires on the mountains. To keep warm at night. I was thinking: we don’t have anything like their initiation, where we become men, do we?’

‘I don’t know,’ Faizal says. The surf fizzes up. Their knees touch. ‘Emile, here. It’s for you.’ Faizal draws a rectangular box from the inner pocket of his jacket.

Emile rubs his arms and looks out to sea, pretending not to have heard.

‘Take it,’ Faizal says. He prods Emile’s shoulder with the box.

Emile takes it and picks at the sticky tape.

‘Come on. Just tear it open.’

Emile pulls the wrapping from the box and lifts its lid. He feels a hollow mass in his chest, but instead of letting it well up, he pushes back, fearing what it holds.

‘I saw it and thought it was so you. Go on. Try it on.’

‘This is unnecessary,’ Emile says, and as he runs the golden necklace through his fingers, it catches the setting sun. ‘I love it though.’

Faizal folds his hands over Emile’s, retrieves the necklace and clasps it around Emile’s neck. Emile winces. ‘It’s beautiful against your skin.’

‘Thank you.’

‘What do you say? Dinner at mine?’

‘I told my mother I’d be back tonight.’

‘You’ll do no such thing. Tonight, you’re staying over. Come on. I’ll make dinner.’

They pull off at a garage. Faizal swerves around the petrol tanks to park in front of the shop.

‘Just getting a few things,’ he says, slamming the car door.

Emile watches as cars pull up. They are fuzzy and dull in the leftover light of the day. A young couple in a GTI sit staring in front of them while a petrol jockey cleans their windscreen.

They have been together for two years. Emile has met Faizal’s mother once, the only woman in a house of men. She flew down to Cape Town for the day. At the lunch, she was impeccably dressed. She ate her salad in small bites. Emile had expected a woman softened by the boisterous presence of four men in the house but her stare raised the hairs on the back of his neck. Faizal introduced him as a friend from his running club.

The car door opens and Faizal gets into the driver’s seat with a grin on his face and two servings of blueberry cheesecake.

The curry is delicious. Faizal has even washed the rice. It tastes clean and fresh.

‘How was the interview?’ Faizal asks.

Emile picks at the chunks of spiced lamb. ‘I won’t get the job.’ His fork clinking against the plate, he scrapes the last of the rice into a little heap. After dinner, they clear the kitchen in routine silence and, with the cheesecake forgotten in the fridge, retreat to the dark living room. A muscular Table Mountain seems pressed up against the wide windows of the eleventh-floor apartment. Emile peers out, and spots a flickering dab of orange on its summit.

As he pictures the Xhosa boys trying to find a way down the crags, their loins on fire, Faizal steals up and grabs Emile around the waist. His free hand pushes Emile’s cheek against the window. ‘You did it again,’ he says.

‘I’m sorry.’

‘You don’t listen,’ Faizal says, punctuating each word with a sharp jab.

Emile visualises the glass pane shattering – sending them plummeting to the street below – and says, ‘Faizal. Please.’

Trembling, Faizal releases his grip. Emile takes the brunt of the punch. He raises a hand to his cut lip, then with each word spraying blood, says, ‘You will leave me, won’t you?’ Forgoing the remorse – the tremble of lines on Faizal’s brow, the curl of his lip that might be mistaken for a smirk – Emile turns to the bathroom, and in the white cabinet above the basin, he finds the little orange box. From it he slides a sliver of steel.

‘You should get it done. It’s just more hygienic,’ Faizal had once said, tugging at his foreskin.

He pulls his trousers and briefs down to his ankles, closes the lid of the toilet and sits down, fumbling with his penis, dark against the white rim. He swallows the blood from his nose. Between thumb and forefinger Emile Oliphant pinches his foreskin, stretches it over the glans of his penis and brings the razor down in a single slice.

— Do you have a place?

— I do, babe.

— Address?

— Sea Point Main Road. Taronga Mansions, number twenty.

— On my way. Give me ten minutes.

It had all started one afternoon as Emile came home from school. In their backyard, under a peach tree that never bore any fruit, he found his father in yellowed underwear, sitting in the dust, legs drawn up, his knuckles bloodied and swollen. He saw Emile, flung a handful of dry, dark earth aside and said, ‘Your mother.’

His mother was in the kitchen slicing green beans, her hair a black veil over her face. ‘It’s because he can’t find a job. Takes a toll on men. Plus, he’s a wild spirit. People like that, good luck with them,’ she said.

Emile shared a nose with his mother. Had he been a girl, he would have moved with the same swing of the hips. With her long, straight hair, green eyes, her full figure, and her free laugh, his mother captivated all sorts of men to a silly degree.

In the years after his father had left, the men kept flocking. After sex, invigorated and their masculinity restored, her lovers would sometimes enter the bathroom and, upon finding Emile in the tub, would make a big show of pissing into the toilet bowl. Up and down, left to right they would aim, their half-turgid members on display for Emile to see. Their raw exhibitionism thrilled the young Emile to no end. Few minded staying behind with Emile, after his mother had left for work. Emile was an easy boy, and they were all too keen to satisfy his endless curiosity.

As his mother grew older and her gait became laboured, the parade of men dwindled. It prompted her to say, ‘It’s because of you, you know.’ For a while Emile lamented the situation, but he was a resourceful boy and soon started gathering his own men. At a precocious fifteen, he would find them in online chatrooms and invite them to the house when his mother was out. Never would the same man visit twice. Emile would block all contact once they had satisfied him. Tall and short, married and single, young and old, they all loved him.

— Sexy.

— Gimme some of that.

— Up for a meet?

— Can’t now. Busy. Maybe later?

— OK.

— More pics?

Unlike the others, Faizal stayed. His online profile suggested something beyond wet, sticky sheets and morning regrets. ‘Are you man enough?’ his introduction read. Emile sent him a message. When Faizal eschewed the usual conversation openers of ‘top or bottom?’ or ‘dick size?’ and asked Emile if he would like to join him for a coffee, Emile, phone in hand, felt the stirrings of something new and settled deeper into the cushions on his bed …

- Lester Walbrugh is from Grabouw in the Western Cape. His acclaimed short stories have been published in, among others, the anthologies of Short.Sharp.Stories and Short Story Day Africa, New Contrast and, most recently, Hair: Weaving & Unpicking Stories of Identity. He has lived in the UK and Japan and is currently back in his hometown, working on his first novel. Let It Fall Where It Will is his debut short story collection.

~~~

Publisher information

Hi,’ he said. He had perfect teeth.

We clinked glasses, his martini with my local craft gin cocktail.

‘Let it fall where it will,’ he said.

The die is cast in Lester Walbrugh’s debut collection of stories. Set in the Western Cape and in Japan, Let It Fall Where It Will showcases the stunning versatility of the author. Ranging from witty to poignant, occasionally employing magic realism to great effect, the stories capture a vibrant chorus of voices and fearlessly explore contemporary topics of identity and sexuality while illuminating South Africa’s troubled past and the shadows it throws on our present.

The rooms are aglow, another morning with portals of light. Its clarity is blinding.