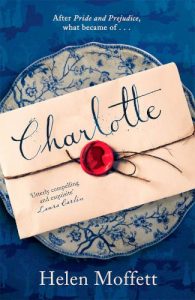

The JRB presents an excerpt from Helen Moffett’s debut solo novel, Charlotte.

Charlotte

Helen Moffett

Bonnier Zaffre, 2020

Read the excerpt:

Mrs Darcy paced up and down the drawing room, as Charlotte tried in vain to make both herself and her guest comfortable, offering a seat by the fire, to send for refreshments. Since finding her son dead, she had found it impossible to settle—to lie or sit or stand in any one place for more than a few minutes—without wanting to leap to her feet and hasten elsewhere, anywhere. It was a while before she realised she was trying to escape pain the same way a mouse would try to escape a toying cat. This made condolence visits even more than usually difficult—while gratified at the kindness of parishioners and neighbours, every several minutes she found herself battling the impulse to rise and flee the room. But this morning Elizabeth outdid her in restlessness. Her face was wan, and there were shadows under the famously brilliant eyes, now immortalised by one of London’s most sought-after portrait artists.

‘I cannot comprehend the enormity of your loss, my dearest Charlotte,’ she said. ‘To lose a beloved child, and a son, not yet four years old! It is too cruel, no matter how much reason—and indeed the teachings of your husband, and the convictions of mine—may attempt to console or soothe.’

She paused and wrung her hands. With the detached part of her brain, Charlotte registered that she had never seen her friend do such a thing before. Elizabeth went on, ‘I do not mean to burden you. That would be unfeeling, a piece of unkindness. But I must impose on our friendship, your patience, and good heart, even at such a time. I miscarried a few months ago. The baby was a boy.’

Charlotte raised her head, surprised and yet not surprised, uncertain what to say. Lizzy burst out, ‘It is the second child I have lost in these past three years. Charlotte, forgive me—while I cannot pretend to understand what it must be to have a living, breathing child perish, how my own losses gnaw at me!’

Now the brilliance of Elizabeth’s eyes owed something to the tears that trembled in them. ‘It has been a shock— ruinous shock—to realise how ill-prepared I was for marriage. How ill-prepared both Mr Darcy and I were. We believed our regard for each other had been tested, that it had grown to overcome all that stood in our way—the distinctions between us, the differences in our temper, his pride, my hasty prejudice. He had done so much for me, my family. His love was in no doubt, and the strength of my feelings matched his. There was nothing, I thought, that we could not discuss, could not face together. I was a fool.’

She sat down at last on the sofa next to her friend, and said, ‘I did not see the truth that stared me in the face: a great man, from a great family, marries for one reason primarily: to beget heirs. Neither of us gave this any thought. We believed that children, a son—or two or three—would present themselves as if by magic. But it has been five and a half years, and there is still no infant in the nursery. I walk through the chambers of that great house, knowing myself to be the envy of many who do not consider me fit for the office of being its mistress. And I pass beneath the eyes of all those portraits, those Darcy ancestors, all witness to my failure, watching me break the chain.’

Charlotte murmured the necessary words of hope and encouragement, or at least she tried to, but Lizzy went on: ‘I live in terror of one of the stone-faced doctors who attend me opining that there can be no more children, or attempts to bear one. If that happens, Charlotte, I swear I shall jump off the Pemberley bridge.’ She began to weep in earnest, as her friend sat dry-eyed beside her. ‘Fitzwilliam would have been better off wedded to a brood mare. For that is what is required for these great estates, these honourable names. Succession. And my husband is of course too much the gentleman to reproach me for my failure in this regard. So we do not and cannot speak of it. And we speak less and less.’

Charlotte’s mind took a vertiginous leap: she had not yet thought of Tom’s death in these terms—of what it might presage for her daughters. And even as she stumbled through the required assurances that Lizzy would surely indeed soon have issue, the thought occurred to her at the same time as her friend put it into words: ‘But what if I give birth to a girl?’

Charlotte felt an old rage rise up in her. Tom was beyond her help, but this was a new anxiety. With her beloved and damaged son gone, and with him the security of his inheritance of the Longbourn estate, how could she safeguard her daughters? How was she to assure them a home and the respectability this proffered, beyond the lottery of matrimony? If Lizzy had daughters, they would at least have considerable dowries—in which case, Pemberley could go to Bonaparte for all Charlotte cared.

Her mind scoured clear by grief, the reality of her situation came into sharp focus: she and her daughters were at risk of falling into the same trap that had yawned before Elizabeth’s family, the Bennets: their future inheritance entailed away from them because they were mere females.

Why had she never taken Mrs Bennet’s anxiety, the ‘nerves’ they had all mocked, seriously? The business of her life was to find her daughters husbands: what else could it be, given the blind roll of the dice that exposed them all to the kind of poverty perhaps worse than that seen in hovels; that of genteel beggary, of imposing upon distant male relatives who had their own children to set up in life, of being grateful for a roof, no matter how reluctantly or resentfully it was offered.

Elizabeth’s marriage had changed all that; indeed, her sister Jane’s alliance with Mr Bingley alone had offered the remaining unmarried Bennet sisters, Mary and Kitty, a substantial degree of protection. While they might one day lack a home to call their own, they need never fear want as long as they could reside with one or the other of their elder sisters. But on the other hand, Charlotte could see there was no way out for the Darcy line; only males could inherit an estate as profitable, as visible as Pemberley.

Charlotte set her lips. Silently, she vowed to spend the rest of her days circumventing the law of the land so that her daughters need fear neither penury nor charity, as had been the case for herself and her sisters, and indeed many of the daughters of the families she knew. She had no idea how to proceed in this regard, and little understanding of what instruments could be useful, but she knew better than most what dogged determination might do.

- Helen Moffett is a South African writer, freelance editor, activist and award-winning poet. She has a PhD on Pre-Raphaelite poetry and has authored or co-authored university textbooks, short story anthologies, non-fiction books on the environment, two poetry collections and various academic projects. Charlotte is her first novel. She blogs at helenmoffett.com and can be found on Twitter.

~~~

Publisher information

For lovers of Pride and Prejudice and Longbourn, an intoxicating novel that tells the story of Charlotte Lucas, who marries the unfortunate Mr Collins after Lizzy Bennet spurns him.

Everybody believes that Charlotte Lucas has no prospects. She is unmarried, plain, poor and reaching a dangerous age. When she stuns the neighbourhood by accepting the proposal of buffoonish clergyman Mr Collins, her best friend Lizzy Bennet is appalled by her decision. Yet this the only way Charlotte knows how to provide for her future. Her married life will propel her into a new world: not only of duty and longed-for children, but secrets, grief, unexpected love and friendship, and a kind of freedom.

Jane Austen cared deeply about the constraints on women in Regency England. This powerful reimagining takes up where Austen left off in Pride and Prejudice, showing us a woman determined to carve a place for herself in the world. Charlotte offers a fresh, feminist addition to the post-Austen canon, beautifully imagined, and brimming with passion and intelligence.