The JRB presents an excerpt from Odyssey To Freedom, the memoir of the late George Bizos.

Bizos passed away in Johannesburg on 9 September, at the age of ninety-two.

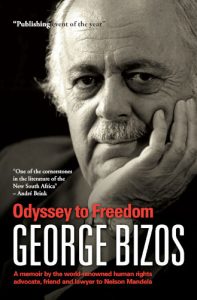

Odyssey To Freedom

George Bizos

Penguin Random House, 2009

In 1941, the thirteen-year-old Bizos and his father helped seven New Zealand soldiers escape Nazi-occupied Greece on a rowboat. From there, were taken to Egypt and spent time in a refugee camp before making their way to South Africa. He would only see his mother again many years later, when she came to Johannesburg in the nineteen-fifties.

Read Bizos’s account of the start of his journey to South Africa:

~~~

A lamb was slaughtered for what turned out to be the last meal we would have as a family. My mother served my grandfather first. He asked for the portion covering the shoulder blade. He removed the meat, took the bone, wiped it clean and raised it up to the lamp in which olive oil was burning. He pronounced it clean of any blemish—a good omen for the success of our venture. While we prepared to leave, one squadron of Stukas after another flew alarmingly low over the village. Frightened by the great noise and, or so we children thought, by the square black cross under their wings, the animals in the field stopped grazing and the donkeys bolted, throwing off the women riding sideways on their backs.

As the planes crossed the bay they looked low enough to touch the sea. Despite the distance, we could hear the frightening roar of their upward ascent when they reached Mount Tyegetos. Then they disappeared over the mountain in a south-easterly direction. Although we did not know it then, the planes were heading for Crete and would drop their deadly cargo over the island. That was also our intended destination, but because of the successful bombing campaign, we would ultimately have to change our plans.

It was in the middle of the last week of May that we went to Kalamaki beach at Faneromeni (nowadays a favourite place for German tourists), our place of departure. It was out of sight of the Nazi occupiers in Koroni and the village. We gathered on the flat rock edging the beach, standing around the provisions to be loaded into the boat. I had been hugged and kissed by my grandparents and mother. My mother and grandmother were in tears, but for me, it was the beginning of an adventure.

While waiting there I learnt for the first time who else was coming with us and heard about a plan of my Uncle Vangos, with whom my father was not on good terms. This uncle, married to my father’ s sister, had arranged that a small, shallow boat would be tied behind ours, on which he would leave with a party chosen by him. As the sun set behind Mavrovouni, our boat emerged from a nearby cove and the two Koroni fishermen carefully brought her to the edge of the rock.

In the growing darkness the New Zealanders left their hiding place, smiling broadly when they saw the boat. We got in and set off at once into the dusk. The favourable north-west wind blew gently but the triangular sail was not hoisted for fear that it might attract attention, even in the failing light. It was decided that we would use the oars until out of sight of those, particularly in Koroni, who may have been looking for any movement towards the open sea.

We had not gone more than a few miles when a battle began between the south-east and north-west winds. This caused a choppy sea and made it impossible to raise the sail. It was decided to veer to the right, and land on the uninhabited island of Venitico, so named because the Venetians used it as an observation post to defend their interests against the Ottoman fleet and the pirates in days gone by.

We spent the night under the bushes on the island, but the New Zealanders were apprehensive and eager to leave, so before dawn we set off again with a good wind making it unnecessary to use the oars. We sailed due south instead of south-east to avoid passing the island of Kythera, where the Germans would surely have a presence. We made good progress until late afternoon, when suddenly gusts of wind swung the sail from side to side, quite out of control. The canvas tore and we had to duck to avoid being hit by the boom. I was told to crawl into the small cupboard in the prow.

For the rest of the journey I stayed there, unable to keep down food or drink. The others took turns at the oars throughout the night. Next morning conditions had improved, but the boat of my Uncle Vangos and his party had come untied from our craft. Ultimately, they made their way back to the mainland and returned home without the Germans ever knowing they had almost escaped.

On our boat, a blanket was tied across the sail to cover the gaping hole and, as we began the third night of our journey, we hoped that the late afternoon winds would not be as bad as they had been the evening before.

Just then the New Zealander holding the tiller pointed westwards towards the setting sun, where he had spotted a number of ships sailing in our direction. There were expressions of both hope and fear – were they British or Italian? Would they stop? Would our fishermen’ s disguise, and the bits of net and floats of coloured calabashes, fool them? Out of his pocket the helmsman took a small mirror. He held it high above his head to catch the sun, then suddenly brought it down again. He repeated this action a number of times, until one of the ships broke away from the convoy and headed towards us at top speed.

There were exclamations of joy from the New Zealanders when it came near enough for them to recognise the flag. As it approached, the ship reduced speed and many of the sailors on deck waved. We had to hold tightly onto the sides of the little boat, as it bobbed up and down on the massive ship’ s bow-waves. Comparative calm was soon restored; our boat was manoeuvred close to the side of the ship, to the applause of those above and ourselves below. We could not understand what the New Zealanders and the sailors were saying, but it did not matter. We knew that we were safe from the perils that the Sea of Crete may have held for us if we spent another night baling water.

One by one we climbed the rope ladder and, as we stepped on board, three or four officers shook each of us by the hand. We were given towels and taken to wash. A doctor examined me in the sickbay and gave me half a glass of sweetened water. My father came to tell me that our boat had been abandoned with all the provisions left in it. He and the others had gathered in the ship’ s dining room, where they heard that Crete was falling to the Germans. Clearly we couldn’t go to Crete, but would be taken to Alexandria instead. The captain thanked my father for the help he had given the soldiers and said we should not worry; there were many Greeks in Alexandria who would look after us.

Nourished by the juice from tins of vegetables, pears and mashed fruit, I soon became well enough to join the others. The dining-room tables were used as beds at night and a hammock was also slung under each table. I slept in a hammock beneath my father.

We could not go to Alexandria directly. Our ship, like the others in the convoy, was off to Crete to help evacuate the Allied Forces as well as the remnants of the Greek army and government.

We remained around Crete for two or three days. Now the fleet no longer sailed in formation, but packs of two or three moved slowly beyond the mouth of the harbour in which many vessels of different sizes were moored. We were told that they were waiting to transport people out of Sitia, the only port not occupied by the Germans. The warships were there to keep at bay the German planes, laden with bombs. When the planes were heard or sighted, the ships moved fast in irregular patterns and fired at them from the deck guns.

I was anxious to see what was happening, but was not allowed on deck and instead had to stay in the dining room out of everybody’ s way. Disappointed at not being allowed to watch the war games, I stood at the door of the dining room watching one shell after another ascending on a conveyor belt, each hurriedly grabbed by a sailor who then ran out of sight towards the middle of the deck. Only once did I feel that we were in danger when the ship made a sudden change of direction, its prow covered by waves with water rushing off the side. The manoeuvre was necessary to avoid a mine.

At first light one morning, the harbour was empty and the fleet withdrew since it had no further purpose to serve there. For some time, we sailed in convoy with the sun behind us until our ship, which I later learned was HMS Kimberley, once again broke away, turning south to take us to Alexandria.

~~~

About the book

A spellbinding autobiography by one of the world’s most admired human rights advocates. This story, told on a grand scale, unfolds from Bizos’s daring rescue of seven New Zealand soldiers from the Nazis as a boy in Greece.

He arrives in Johannesburg together with his father, penniless and unable to speak English. He studies law at Wits University and becomes an advocate, building a career on defending the downtrodden against apartheid abuses in a hostile justice system. He becomes the defender of Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu and the families of Steve Biko, Chris Hani and the Cradock Four. He mediates in the events around Winnie Mandela and even defends Morgan Tsvangirai in Zimbabwe.

These cases are related as gripping courtroom dramas, augmented by the drama behind the scenes.

His whole remarkable, courageous and beneficial life told by himself in astonishing detail, involving hundreds of colourful characters and anecdotes.