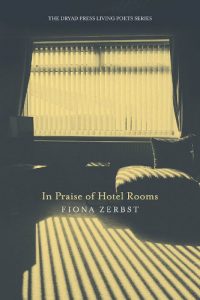

Rustum Kozain reviews In Praise of Hotel Rooms, the fifth collection of poetry by Fiona Zerbst, calling it ‘a fine collection of poetry by one of South Africa’s finest poets’.

In Praise of Hotel Rooms

Fiona Zerbst

Dryad Press, 2020

What is it that draws me to Fiona Zerbst’s poetry? When I first read her work, back in 1991 with her debut, Parting Shots, I was struck by the assuredness of the poetic voice. Enrolled for an MA in English Literature, I also fancied myself an aspirant poet. But, for all my pretension, I was struck by the maturity and control in the poetry of Parting Shots—struck, not without envy, that here was someone younger than me whose poetry read as the writing of a fully formed poet. A real poet against whose work my own writing then amounted to so much scrimshandering. I admired the poetry, but also envied that gift. I do not know how many times and hours I have stared at ‘Mandelstam: A Photograph’, trying to unlock Zerbst’s secrets. How could she see what she sees in a photograph of a long dead Russian poet: ‘Your face, retentive as broken stone’?

With In Praise of Hotel Rooms, Zerbst’s fifth volume, that admiration has deepened, and so has the envy. Feckless, despairing Romantic that I am, I have to admire the commitment to a poetry that comes from work—perhaps even dogged work—and which pushes through the surfeit of language in our loud internet age. As Zerbst writes in ‘Tools’:

still I come

to lay them [words] out

row after row,

used before,

honest with use,

or stunted, solid,

rusted, worn,

dull as a hoe.

In Zerbst’s ars poetica, the work of poetry, of writing, leads, counter-intuitively, to a certain plainness—‘all glamour gone’—but a plainness that lies beyond the utilitarian. Or, put another way, the utility of poetry lies in its very refusal, paradoxically, to be useful: a ‘useful blankness’. A useful, glamourless blankness.

I think it valuable to think of poetry as sometimes divested from glamour and from usefulness. At present, we witness demands that writing and art exhibit full-spectrum awareness. Artfulness that doesn’t address present urgencies is seen as an impoverished art. I myself suffer from an anxiety that poetry is ‘useless’ in the face of myriad barbarisms and injustices perpetrated by political and economic elites, while we consume terabytes of glamourous audiovisual mass culture and shout out our grievances and hurt at each other. And we get louder and louder—listen to me!—because the elites, the people who have power over us, aren’t listening.

Reading Zerbst’s poetry reminds us that there are parts of our lives that cannot be addressed via loudhailers—difficult parts, like the loss of love or the loss of a loved one to death, that are best approached through a language tempered by reflection. Zerbst’s poetry is not a poetry of ready-made insights or easy resolutions. As the title poem that opens the book implies, poetry is also to be found in those moments that cannot be captured exactly or in their fullness: ‘That hush behind curtains/ you can’t describe later’.

The moment or experience or emotion that evades description … to make poetry out of that, to communicate the ineffable or unsayable, is Zerbst’s metier and her deft hand can treat serious matters with a light touch without sacrificing the gravitas of the subject matter. Because the language isn’t clamouring for attention—because, in a way, the poetry refuses the terms of ‘normal’ communication that requires ever loudening, clamouring language—the reader trusts the voice. The voice does not draw attention to its performance. The upshot is that the writer disappears from the text—the words on the page appear as if natural, effortless. There is no straining towards the poetic.

This quality in Zerbst’s poetry is what draws me back to the writing—the deft touch, the seemingly effortless poetry. Eschewing the glamour, I suppose, of topical material, staying true to some inner vision of what is true and sincere to her—writing on her own terms—one cannot help but turn her lines over and over in the head and mouth. Here is an epiphanic moment from the end of ‘Presentiments’:

… And between us –

this line of coast and me –

that dried-out puzzle of salt

on a maze-like path of sand.

A chunk of coast in a crescent

where at last I came to rest

after years of loneliness,

presentiments of death.

Look again at the ordinary or plain language in the above—the language or words ‘honest with use’ as described in ‘Tools’. The syntax too is straightforward. But there is something going on in ‘A chunk of coast in a crescent/ where at last I came to rest’, something that comes as a surprise, perhaps because of the syntactical variation. Compared to these lines, the first half of the poem is fairly prosaic with the two main clauses being ‘I remember this chunk of coast …’ and ‘I recall/ the houses’. Then, a few fragments—i.e. lines without main, finite verbs. Then, the final four lines, also a fragment, but with the subordinate clause ‘where at last I came to rest’. The line that is the centre of gravity of the poem—weighted further by the two lines following—is at the same time a line that is metrically more alive than the rest of the poem. That’s deft and artful.

In ‘The Bay’, Zerbst commemorates her friend and mentor, Stephen Watson. As heavy as the heart may be, Zerbst again uses her deft touch to conjure the late poet while avoiding the maudlin: the sea ‘offers up waves in which you wade/ until you’re almost solid again/ alive within the poems you made’. This nexus of creative forces—poetry, the sea, conjuring—brings to the fore another quality I envy in Zerbst’s poetry—its spectral nature. It should be clear that I do not mean this in any morbid, ghostly sense. I’m trying to describe, rather, a quality in the poetry where the heavy and the light are held in tension. Or where the seen and the unseen co-exist. Where the ineffable and the elusive are not big cosmic riddles, but neither are they ephemeral—ordinary as a ‘hush behind curtains’ (‘In Praise of Hotel Rooms’) or a ‘huge, dark animal’ (‘After-Image).

To approach it from the opposite direction: Zerbst’s poetry is deceptively ‘light’, but there is almost always a shadowy something about—a presentiment, an unknown animal, a past love. And then, treated with her characteristic deftness, at fine pitch in filigreed verse (‘Herringbone-fine’ as she describes a seahorse in ‘Knysna Seahorse’), the elusive nature of memories of a past love (‘One Night in Kyiv’ and ‘Odessa Days’) ring true. The representation of that elusiveness is convincing.

In Praise of Hotel Rooms is a fine collection of poetry by one of South Africa’s finest poets. That this is her fifth volume of poetry is also an indication of Zerbst’s commitment to her art, given that few poets in South Africa go on to publish more than one or two books, and despite the fact that Zerbst has received scant attention from prize committees. Dryad Press should consider bringing out a meaty selected volume of her work.

- Rustum Kozain is The JRB Poetry Editor. He is the author of This Carting Life (2005) and Groundwork (2012), both of which won the Olive Schreiner Prize, as well as, respectively, the Ingrid Jonker Prize and the Herman Charles Bosman Award. His poetry has been published in translation in French, Indonesian, Italian and Spanish. Follow him on Twitter.